Advancement in metals recycling technology means that China will probably need no new minerals for making electric vehicle batteries by 2042, according to the founder of Fujian-based battery manufacturing giant Contemporary Amperex Technology (CATL).

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

Chairman Dr Robin Zeng also told the World Economic Forum meeting in Davos, Switzerland, on Wednesday that the sharing of recycling know-how with Europe and the United States, barring geopolitics, will help ease an expected supply crunch in key minerals such as lithium and nickel.

Electric vehicles are gaining popularity worldwide as an alternative to oil-guzzling cars. But manufacturing the new builds, particularly their large batteries, is straining mining supply chains which insiders say have faced years of underinvestment.

China is by far the world’s largest maker and user of electric cars, so a future freeze in metals demand from the country could put the brakes on global mineral exploration and extraction.

Zeng said that CATL can currently recover up to 99.6 per cent of nickel, cobalt and manganese from its products, as well as 91 per cent for lithium. He said the firm’s recycling subsidiary, Brunp, last year handled 100,000 tonnes of waste batteries and produced 13,000 tonnes of lithium carbonate from them.

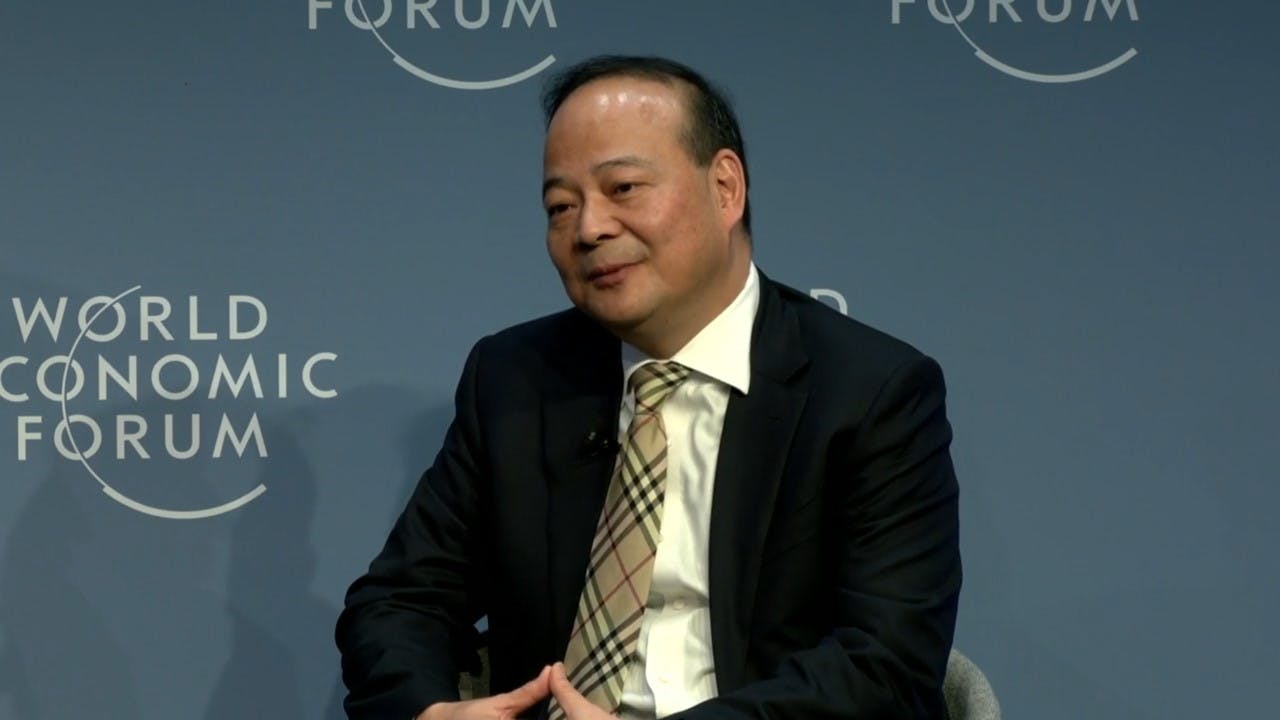

Dr Robin Zeng, chairman and general manager of CATL, speaking at the World Economic Forum annual meeting in Davos. Image: WEF.

“At the end of the day, if we get to 100 per cent electric cars, then recycling will provide a lot of benefits in [resolving mining issues],” Zeng added.

The supply of nickel, cobalt and lithium – key metals in making electric car batteries – is currently sufficient to meet global demand, but a squeeze on these transition minerals is expected close to the end of the decade.

However, estimates are that only about 5 per cent of electric car batteries are currently recycled, with lithium particularly difficult and expensive to extract from spent cells.

The problem is set to grow. Consultancy McKinsey & Company said last year that while there are about 130 kilotonnes of dead batteries globally in 2020, the total weight will rise to over 19,270 kilotonnes by 2040, when hundreds of millions of electric cars are expected to ply the roads.

Most of the world’s current battery production and recycling capacity is in China. Zeng said that the sharing of recycling expertise should not be ensnared in geopolitics.

“If we can provide recycling technology to Europe, the United States and the rest of the world, it will be easy to manage mining issues,” Zeng said, adding that European facilities can only recover 70 per cent of the lithium they process and 80 per cent of the nickel and cobalt, compared to the 90 per cent-plus recovery rates in China.

As it stands, clean energy technology is widely regarded as one of the fronts of a brewing trade war between the West and a fast-rising China. The United States has already slapped heavy taxes on solar panel imports from Chinese manufacturers, among other products such as advanced computer chips.

Both the United States and Europe are trying to grow their domestic electric car supply chain, and there are murmurs of additional taxes on Chinese imports in both jurisdictions.

Miners face funding woes

Demand for new mines is unlikely to dip in the short run. CATL itself secured exploration rights at a Chinese lithium mine last year, and is reportedly considering more domestic acquisitions. It is also developing a megaproject in Indonesia that will cover everything from nickel mining to processing, battery manufacturing, and recycling.

Nonetheless, miners have said they are not receiving enough funds to meet future demand from the clean energy sector.

At a Davos panel that CATL’s Zeng was speaking at, an audience poll showed that three in four attendees expected shortages in minerals critical to the energy transition by 2030. They said suppliers, buyers and financiers need to work better together, and that more innovation is needed across the value chain.

Benedikt Sobotka, chief of Luxembourg-based Eurasian Resources Group, said the situation was “a perfect storm”.

“When I speak to the large investment funds, the big pension funds, they actually do not like mining. They like to have sustainable products, but they do not really like to be invested in [mining],” Sobotka said, attributing the issue to politics as well as perceived environmental, social and governance (ESG) risks.

He was challenged by Kristin Andresen, whose family owns Ferd, a Norwegian investment company, on problems concerning human rights, recycling and deep sea mining.

“We are looking into a lot of problems with your business,” Andresen said, drawing a reply from Sobotka that there is “nothing of what you have just listed” in Eurasian Resources Group’s operations, and that there is an “incredible” amount of misunderstanding and distrust in the financial sector and civil society.

End-users are also looking at technologies that will distance themselves from mineral shortages.

CATL is increasingly developing lithium iron phosphate batteries, which do not use nickel or cobalt. Sumant Sinha, chairman of Indian clean energy firm ReNew Power, said rising lithium prices spur interest in novel alternatives such as gravity-based power storage, where heavy loads are lifted by surplus electricity and later lowered to drive generators.

But there are fewer opportunities for substituting materials such as copper, steel and aluminium, which are core ingredients in electrical wiring and buildings, Sinha said.