Rising sea-levels could inflict US$724 billion in economic damage to seven of Asia’s major cities this decade, a report by environmental campaigners Greenpeace has cautioned.

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

Around 600 million people live in low-lying coastal regions at risk of flooding, with 11 of the 15 highest risk cities in Asia, as the concentration of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere continues to build, and the rate of sea-level rise accelerates.

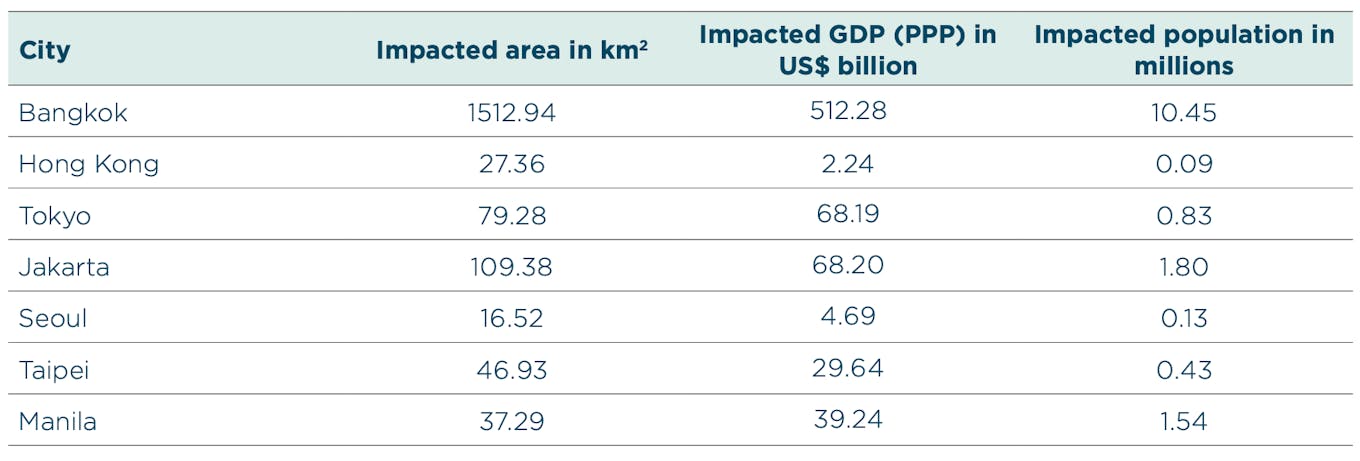

Greenpeace’s report projected the economic risk from sea-level rise to Hong Kong, Taipei, Seoul, Tokyo, Jakarta, Manila and Bangkok if greenhouse gas emissions and global temperatures continue to rise at the current rate.

The report is the first of its kind to use high spatial resolution data to predict which areas of each city are most at risk from floods, and gauged the effects of sea-level rise on population, land area and gross domestic product (GPD).

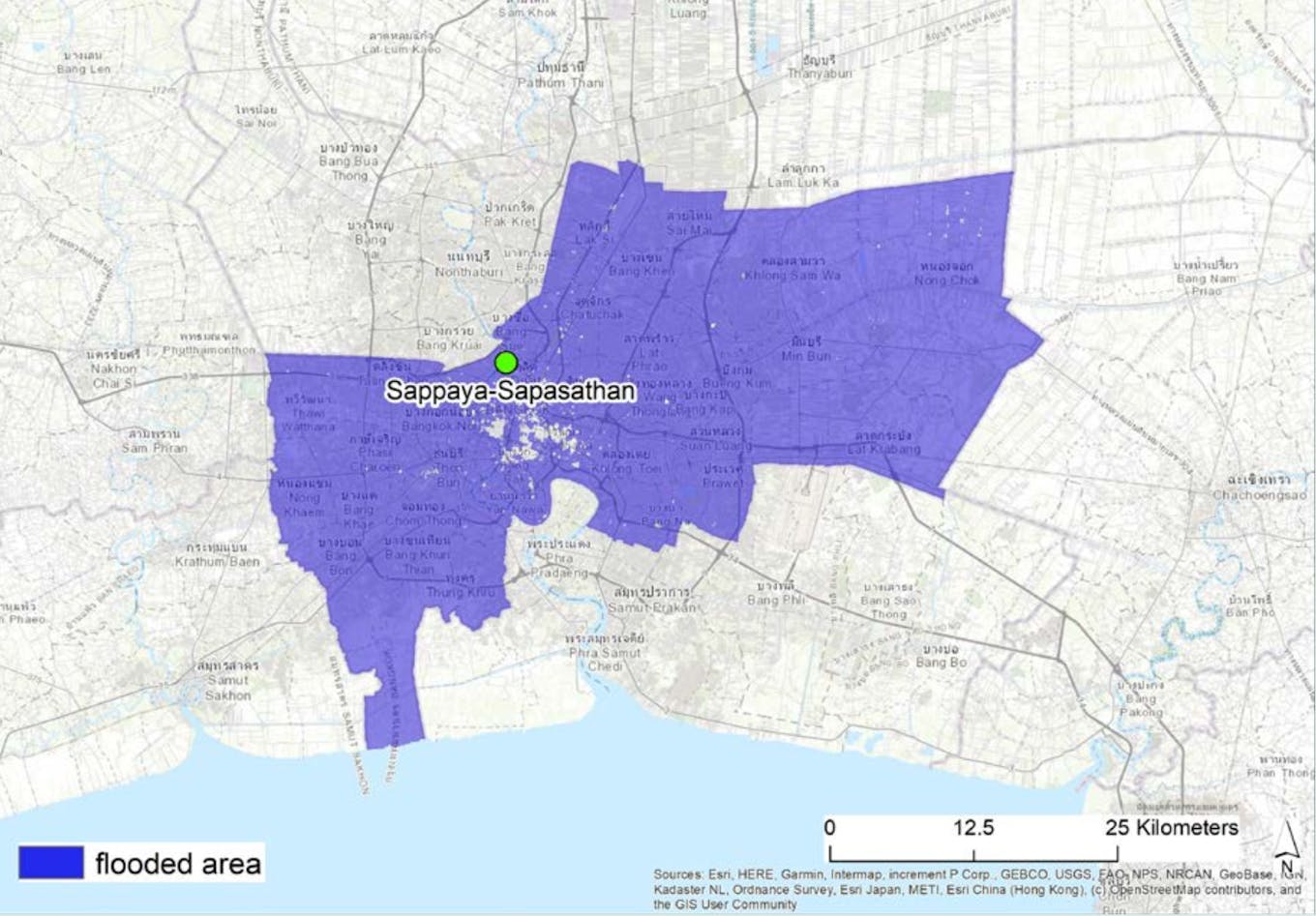

Asia’s most severely hit city by rising seas will be Bangkok. Some 1,500 square kilometres of the Thai capital’s land area could affected by regular flooding by 2030, according to Greenpeace’s analysis. This will mean that 96 per cent of the city’s GDP — worth US$500 billion — and more than 10 million people will be affected.

Bangkok is already flood prone. Soft soils, urbanisation and land subsidence combine to sink the city by an average of 30 millimetres a year. Rising sea-levels could exacerbate flooding, and worsen the salination of the water supply. Last year, drinking water had to be trucked into Bangkok after a period of drought and rising seas pushed seawater up the depleted Chao Phraya River.

Flooding may not only affect Bangkok’s densely residential and commercial areas in the city centre, such as Silom/Sathorn and Wireless/Ploenchit, but industrial as well as large agricultural areas on the outskirts of the city, the report finds. The Sappaya-Sapasathan, the new parliament house of Thailand, could also be submerged.

The potential impact of sea-level rise and coastal flooding in Bangkok in 2030, under a 3-4°C global warming scenario. Source: Greenpeace

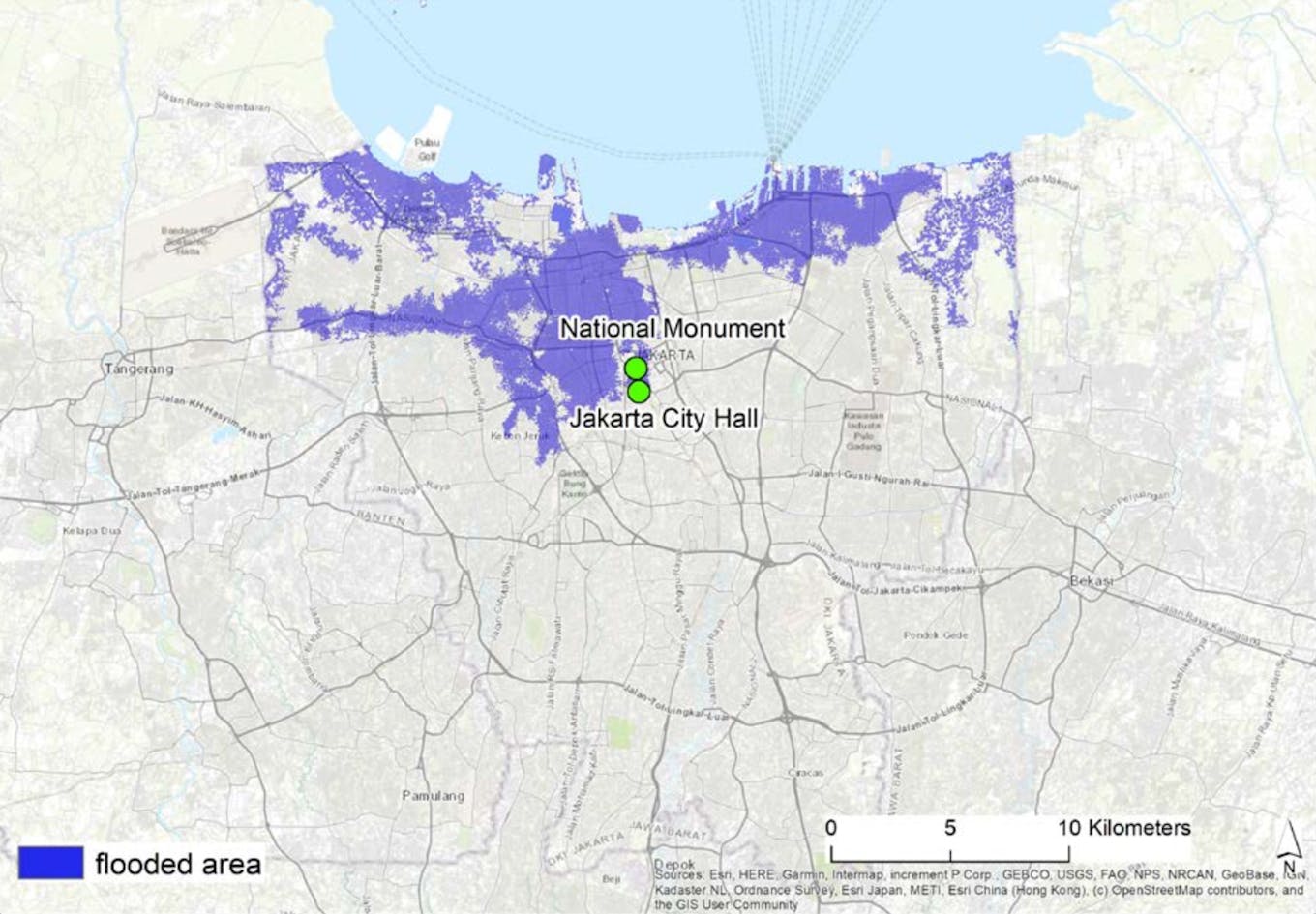

Jakarta, which has been dubbed the world’s fastest sinking city, is the next most vulnerable place in the study. The Indonesian capital, which was earmarked for a move to Borneo because of chronic subsidence and flooding problems until the Covid-19 pandemic put those plans on hold, stands to lose 18 per cent of its GDP, with 1.8 million people being affected by flooding by 2030.

Almost 17 per cent of Jakarta’s land area is below the level to which sea water could rise if major flooding occurred over the next 10 years, with the northern parts of the city, including residential and commercial buildings, the National Monument and Jakarta City Hall, at most risk. Around 95 per cent of North Jakarta is expected to be submerged by 2050.

The potential impact of sea-level rise and coastal flooding in Jakarta in 2030, under a 3-4°C global warming scenario. Source: Greenpeace

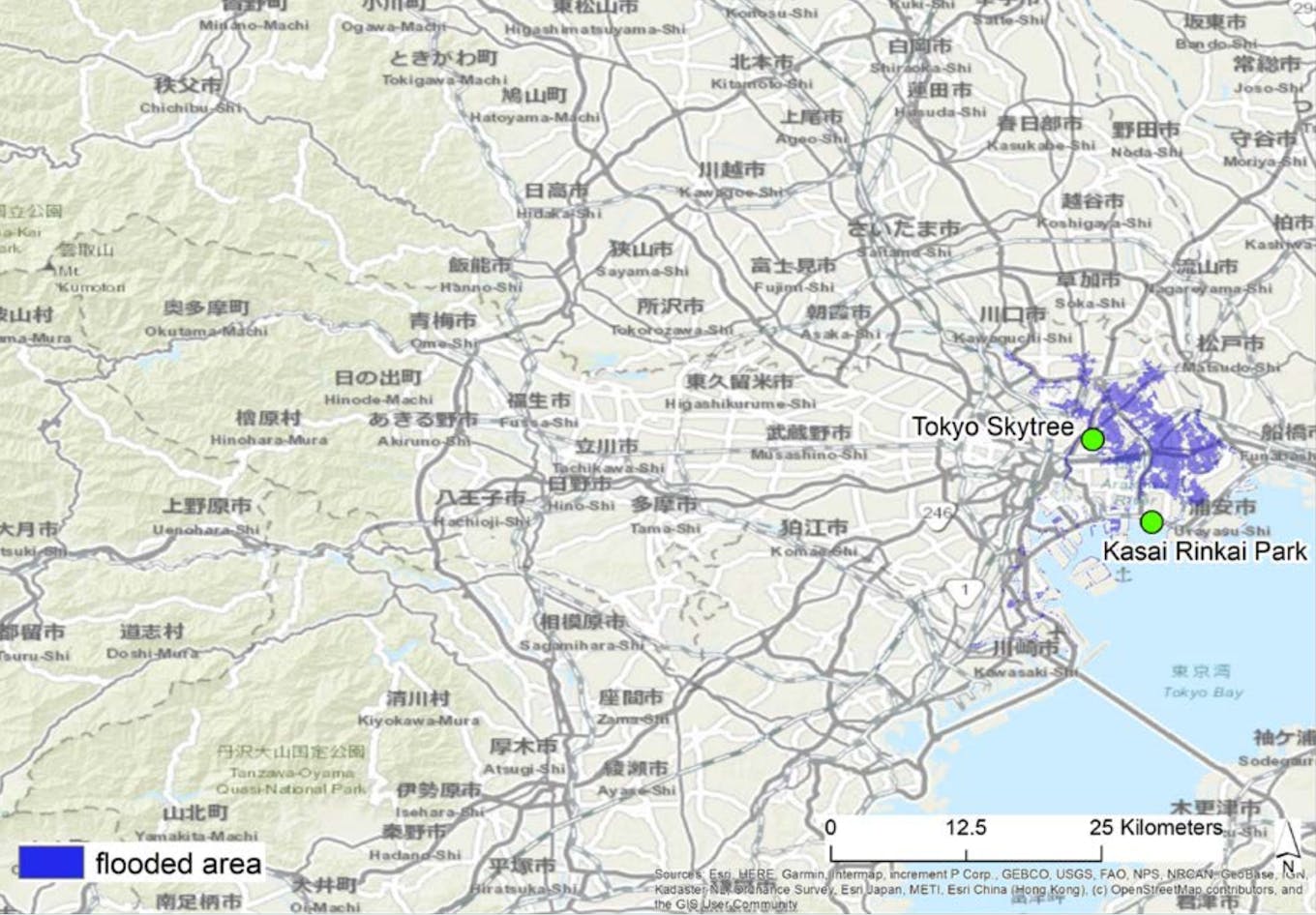

Tokyo risks sustaining about the same economic losses (US$68 billion) as Jakarta to rising sea levels over the coming decade, although most of the Japan capital is located higher above sea-level. Tokyo’s most at-risk areas are home to 830,000 inhabitants and 7 per cent of GDP, and could include Kasai Rinkai Park, which is built on reclaimed land, Tokyo Skytree, and parks along the Arakawa River, which are popular destinations to watch cherry trees bloom in spring.

Parts of Tokyo that could be flooded if the city experiences sea-level rise and coastal flooding in 2030, under a 3-4°C global warming scenario. Image: Greenpeace

Hong Kong’s wealthiest parts in the financial district of Hong Kong Island and Kowloon will largely be spared from rising sea levels, but the territory’s most biodiverse natural areas, such as the low-lying Mai Po Nature Reserve, will be most at risk of flooding, according to Greenpeace’s analysis.

Like Hong Kong, Taipei is typhoon-prone, and the Taiwanese capital suffered a flood subway system in 2001 after storm surges and high tides during Typhoon Nari. Taipei’s western quarter, particularly areas along the Tamsui River, are most at risk from sea-level rise.

Both of these wealthy east Asian cities have less to lose from rising sea levels than Manila in the Philippines, which could see 87 per cent of its GDP affected by regular pummelings from typhoons and extreme flooding. Historical landmarks and popular tourist destinations such as Binondo, Intramuros, Malacanang Palace, and the Jose Rizal National Monument in Luneta Park could be immersed in floodwater by 2030.

Seoul, capital of South Korea, will be the least impacted, partially because it is not a coastal city, but low-lying areas near the banks of the Han River and the Anyangcheon River could be severely affected in the near future, with 1 per cent of the city’s GDP at risk.

The report estimates 15 million people in these seven cities will live in areas at risk from rising sea levels by 2030.

2030 projections for the impact of sea-level rise on seven major Asian cities. Source: Greenpeace

The report does not account for various measures that some cities are putting in place to mitigate sea-level rise. Jakarta, for instance, has erected some flood barriers and sea dykes to protect the northern part of the city, and a 32-kilometre long sea wall is being constructed around the city, although the effectiveness of the wall has been called into question.

Some 641 of China’s 654 largest cities are affected by regular flooding, particularly those on the coast, including commercial capital Shanghai. China has had to relocate millions of citizens, and its “sponge cities” strategy plans to ensure that all of its urban centres can absorb or reuse storm water.

Singapore, which projects mean sea level rise of up to 1 metre by the end of the century, hatched a US$100 billion plan to adapt to rising waters last year, with measures including raised buildings, sea walls, polders, and new islands made from reclaimed land.

However, countries that risk losing most to sea-level rise have been relatively slow to respond to the problem by reducing greenhouse gas emissions. Indonesia’s declaration that it would achieve net-zero emissions by 2070 has been criticised as being insufficient, particularly since China, the world’s biggest emitter, has set a net-zero target for 2060. The Philippines is set to announce a carbon neutrality commitment later this year.

“Governments across Asia must take responsibility to meet the international climate target of achieving a 1.5°C pathway to protect the economy, safeguard the lives and livelihoods of their countries’ residents, and help to conserve biodiversity,” the report said.