As opposition to the controversial pursuit of ocean minerals gathers steam, Singapore has affirmed its support for deep-sea mining. The island nation also said sea-floor extraction must be done according to “robust rules, regulations and procedures for the protection of the marine environment.”

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

The city-state’s Ministry of Trade and Industry (MTI) told Eco-Business that it “fully supports” efforts by the regulator of the deep sea, the United Nations-affiliated International Seabed Authority (ISA), “to ensure that harmful effects arising from deep-seabed mining activities are adequately monitored, addressed and mitigated.”

The ministry’s comments were made in response to Eco-Business’ queries about the country’s position on deep-sea mining after Singapore made a series of non-binding pledges to protect the ocean at the United Nations Ocean Conference (UNOC) in Lisbon, Portugal.

Though not currently permitted in international waters, industrial-scale seabed mining could go ahead in the Pacific Ocean as soon as July next year, once regulations are ironed out by the ISA — a prospect that prompted protests at the UNOC and an alliance formed by Pacific island states to oppose it.

Chile called for a 15-year delay on the deadline to finalise ocean mining regulations, while France premier Emmanuel Macron told journalists at UNOC there should be a legal framework to block deep-sea extraction.

“

Singapore has a rich heritage of leadership in and contributions to ocean-related multilateral processes, and firmly subscribes to the importance of safeguarding the health of the ocean and protecting the marine environment.

We believe that any deep-seabed mining activity has to be subject to robust rules, regulations and procedures for the protection of the marine environment. Singapore fully supports the ongoing efforts by the International Seabed Authority to ensure that harmful effects arising from deep-seabed mining activities are adequately monitored, addressed and mitigated.

Singapore’s Ministry of Trade and Industry

A protest against deep-sea mining at the UN Ocean Conference in Lisbon, Portugal on 30 June. Image: Kate Yeo

Singapore is among a number of countries pushing for ocean mining, including Germany, United Kingdom, Japan, South Korea, United States, Russia and Australia.

These countries, and the mining companies they sponsor, contend that extracting minerals from the ocean floor is necessary to fuel the transition to clean energy.

Singapore is the home country of Rena Lee, Ambassador for Oceans and Law of the Sea Issues and Special Envoy of the Minister for Foreign Affairs of Singapore, who in 2018 was elected president of a conference working towards an international treaty to sustainably manage the high seas, also known as Marine Biodiversity of Areas Beyond National Jurisdiction (BBNJ).

Sian Owen, director of the Deep Sea Conservation Coalition, an alliance of over 100 international organisations working to protect the high seas, said that Singapore’s position of influence over the treaty, and support for deep-sea mining, are “fundamentally incompatible and at odds.”

“Any country engaged in the ongoing negotiations around the “high seas treaty” to protect and sustainably manage BBNJ is unravelling a significant amount of the good that such a treaty would do if they are simultaneously negotiating at the ISA towards opening one of our planet’s last wildernesses,” she told Eco-Business.

Singapore passed an act in 2015 for mining firms to explore the ocean depths. Ocean Mineral Singapore, a subsidiary of Keppel Offshore & Marine (KOM), was granted exploration rights for an area of the Pacific known as the Clarion-Clipperton Zone (CCZ) spanning 58,000 square kilometres — roughly 80 times the size of Singapore.

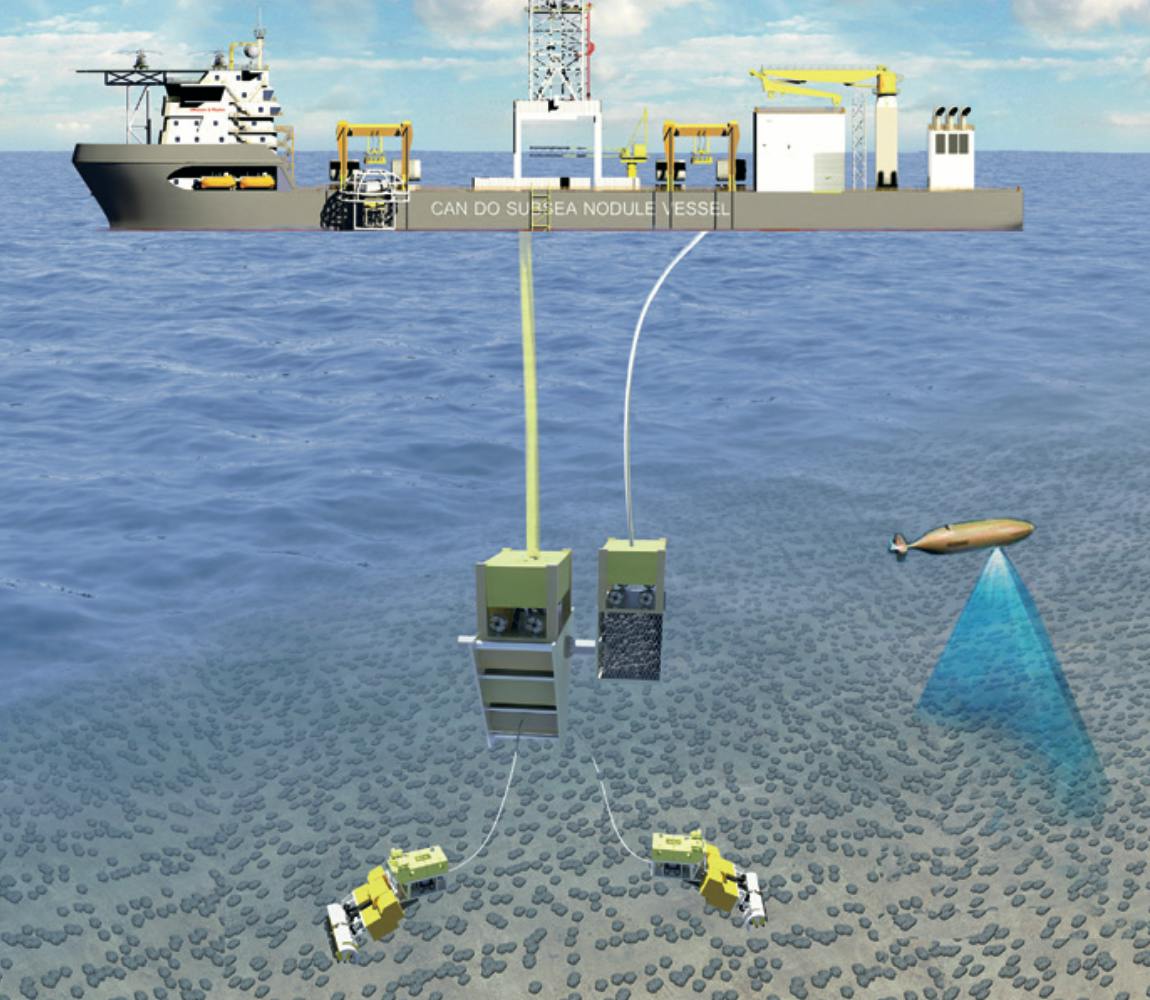

An llustration of how Keppel Offshore & Marine’s polymetallic nodule collector works. Image: Keppel Offshore & Marine

In a 2020 newsletter, KOM detailed how polymetallic nodules, potato-sized formations of metals such as nickel, cobalt, copper and rare earths, could be minded from the CCZ “in an environmentally responsible way”.

KOM has not responded to Eco-Business’ queries about the findings from its exploration, or how deep-sea mining can be carried out sustainably.

A report published in April by 30 scientists concluded that deep-sea mining should not go ahead until more is known about its impacts on marine habitats.

Environmentalists fear that mining the ocean depths could obliterate unique ecosystems, decimate fisheries and choke filter-feeders such as whales with sediment plumes from mining vessels.

“Nobody has yet presented any vaguely credible approach to mitigate these impacts that would be in keeping with the commitment of all countries to Sustainable Development Goal 14, to conserve and sustainably use the oceans,” said Owen, who helped forge the alliance of Pacific island nations backing a moratorium on seabed mining at UNOC.

Owen said there was a need to “review and reform” the International Seabed Authority, which an investigation by the LA Times in April alleged was compromised by pro-mining bias. ISA has rejected these claims.

She said new technologies, such as batteries made from sand and improved recycling techniques, are “rendering obsolete the need to destroy biodiversity to mine for new metals.”

Countries that have called for a ban on deep-sea mining until more is known of its impacts include Chile, Fiji, France, Palau, Samoa, Solomon Islands, and Tuvalu.

Some banks and consumer-facing brands have pledged to avoid financing deep-sea mining projects or use metals mined from the ocean in their supply chains in response to growing opposition to ocean mining from consumers.