Smallholder farmers who cultivate 50 hectares of land or less are responsible for about 40 per cent of global palm oil production, but seem to take a much larger proportion of the blame for the hazy peatland fires that choke much of Southeast Asia on an almost annual basis.

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

In October, at the peak of the fire season in Indonesia, a story by Reuters on why Southeast Asia continues to experience transboundary haze pointed to Indonesian smallholders, who often use slash-and-burn techniques to clear the land to make way for plantations. Large agribusinesses must comply with sustainable palm oil standards, which do not allow burning, the news outlet reported.

This is not a fair assessment of the problem, argues Aida Greenbury, sustainability advisor for the Indonesian independent smallholders union, or Serikat Petani Kelapa Sawit (SPKS).

“The media, in the West as well as Asia, repeats the same message – that it is smallholders who are to blame [for the haze]. But if you dig deeper, you’ll find that it is not that simple,” she said.

While independent smallholders, who are self-managed and are not tied to any particular company, may practise some traditional slash and burn to clear the land, it is industrial timber and oil palm plantations that have drained the peatlands on a massive scale, leaving them vulnerable to the fires that have blighted the region for four decades.

“

Much of the deforestation is still being done by companies, not by smallholders.

Aida Greenbury, sustainability advisor, Indonesian smallholders union

Aida Greenbury, sustainability advisor, Serikat Petani Kelapa Sawit (SPKS), the Indonesian independent smallholders union

Large palm oil companies and governments in producer countries have pushed their narrative onto the media, while smallholders do not have the resources, capacity or platform to tell their side of the story, said the former chief sustainability officer of paper giant Asia Pulp and Paper.

One major issue that is often buried is the reality that smallholders’ land – particularly that of Indigenous smallholder farmers – is no longer recognised as theirs, as it has been occupied or gazetted as production areas, said Greenbury.

A report by non-profit The Gecko Project last year highlighted incidences of subsistence Indigenous farmers in Indonesia, who agreed to give control of their ancestral lands to palm oil companies in the 1990s in return for a cut of profits from oil palms, only to receive nothing in return.

Maybe these farmers didn’t know better, as the idea of Free, Prior and Informed Consent (FPIC) was not well established back then, but now is the time to address that legacy, said Greenbury. “Nobody wants to talk about it,” she said. “But like it or not, we need to address it.”

In this interview with Eco-Business, Greenbury talks about how smallholders have been scapegoated for the peatlands fires, how her organisation is preparing small farmers for European anti-deforestation regulations and why big palm oil companies have no choice but to pay fair wages and prices to smallholders.

Indonesia’s independent smallholders tend to be blamed for the haze, because of the use of traditional slash-and-burn techniques to clear land for planting. Is this a fair assessment of the problem, in your view?

Not really.

Arguments put forward by some parties against traditional slash-and-burn practices are usually based on an unwillingness to respect Indigenous Peoples’ rights, to address the core of land use planning problems, and a tendency to blame the voiceless smallholders.

Indonesia is one of the countries in Southeast Asia that has a long history of swidden, or shifting cultivation, that dates back hundreds of years. This system was sustainable then and can still be sustainable today.

We have learnt that slash-and-burn practices provide several benefits to farmers, including the preparation of planting areas, reduced weeds and the elimination of pests and diseases, ash that serves as a fertiliser, and improved soil structure which allows for faster seedling establishment – all at a lower cost.

Shifting cultivation by smallholders has been blamed for the fires as far back as 1982. If you look closely, before 1970, there was no trend of severe forest loss. But since then, export-orientated timber production, commercial forestry, and the expansion of industrial oil palm plantations without the consent of Indigenous peoples and local communities has occurred, leading to rapid deforestation and the drainage of peatlands, which has turned the soil into flammable material, resulting in unstable landscapes that can no longer support traditional practices.

To stop this from getting worse, we need to stabilise the landscape. Massive changes must be made step by step. They include revising land use plans based on input from Indigenous peoples and local communities, up-to-date conservation value and high carbon stock mapping, paludiculture [agriculture on wet soils, particularly peatlands], halting deforestation, forest restoration, and fair treatment for smallholders. We need to tackle it from all directions.

Smallholders are the victims of haze, not the cause of haze.

It is legal for smallholders in Indonesia to burn some land, although there has been talk about that allowance being withdrawn by policymakers. What is your take on the impact that legal change could have on smallholders?

As far as I know, according to some regulations (Environment Ministry Regulation LH10/2010, Job Creation Law, Provincial Regulations), slash and burn is illegal in Indonesia with the exception of customary communities who clear land by observing local wisdom in their respective regions where slash and burn is allowed for a maximum land area of two hectares per household to be planted with local crop varieties and surrounded by firebreaks to prevent the spread of fire to adjacent areas. This means that land clearing by burning is allowed under certain conditions, but not in protected peat ecosystems nor during extreme dry seasons.

Regulations that respect local wisdom are commendable. However, they cannot work in isolation. In terms of forest fires, the implementation of the above regulations can have the desired impact only if there are real efforts to stabilise the landscape and if farmers are empowered and incentivised to implement climate-smart sustainable practices, and are not living in poverty.

Without such support, farmers will always be scapegoats whenever forest fires and haze envelop the region.

SPKS is working on helping independent smallholders comply with the EU Deforestation Law (EUDR), which includes requirements for full traceability back to the farm where the crop is grown. Do you think that complying with the EU’s new rules is realistic for independent smallholders?

Yes, complying with EUDR is realistic for smallholders. SPKS has proven that it is possible by having a data collection and traceability system from plantation to the mill and by supporting independent smallholders in the establishment of institutions to store and manage traceability data. However, this carries costs and it is essential that those in the palm oil supply chain and governments provide financial support to smallholders and their partners to achieve this.

In addition, current Indonesian government regulations and policies, including Presidential Instruction Number 6, Number 8 of 2018 and Number 44 of 2020 are in line with legality and traceability requirements under the EUDR. Instead of political bickering and accusing the EU of discriminating against smallholders, the efforts made by SPKS and Indonesia’s policy implementation should be supported, replicated and accelerated before the EUDR regulation comes into force on 30 December 2024 for larger companies and 30 June 2025 for small- to medium-sized enterprises.

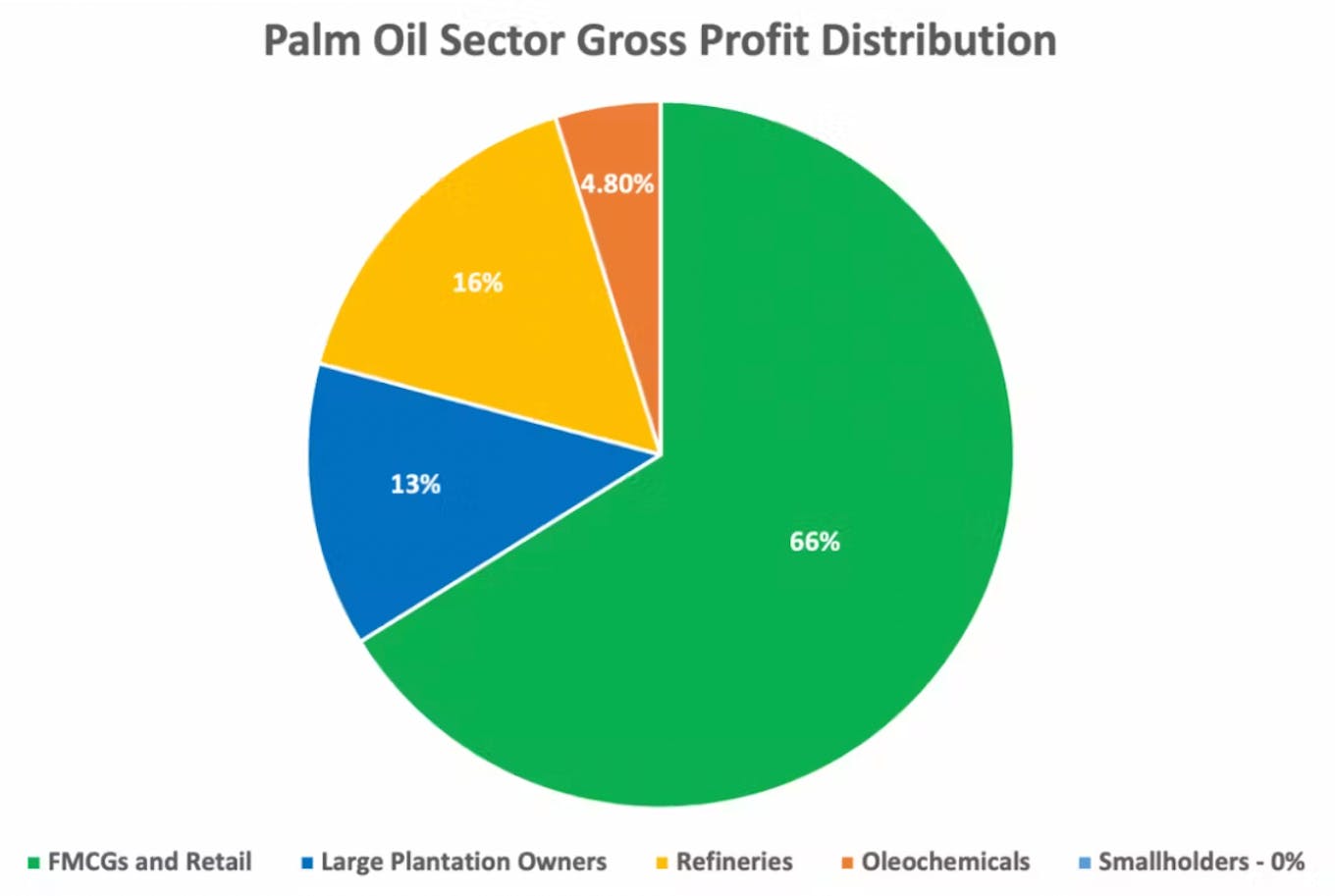

Profit distribution in the palm oil sector. Smallholder farmers take almost zero per cent share of the profits. Source: Chain Reaction Research

A report by Chain Reaction Research in 2021 found that fast-moving consumer goods companies would require, on average, a 1.8 per cent price increase on products containing palm oil in order to finance all costs to make them nearly free of deforestation. The study also found that although smallholders generate US$17 billion for the palm oil sector, which is 6 per cent of the entire value chain, their share in profits is close to zero [see chart].

The European Commission’s impact assessment has estimated that the EUDR compliance-related costs for companies are likely to amount to between US$170 million and US$2.5 billion per year. Such costs would either need to be “absorbed by a reduction of profit by operators along the value chain and/or eventually passed on to the final consumer” in the EU member states.

These two findings support each other. Combined with greater financial support from the EU and Indonesian governments, I believe that targeted EUDR compliance by smallholders can be achieved.

The EUDR is part of the EU Green Deal. Support to smallholders is essential and in line with the EU Green Deal policy of ‘leave no one behind’.

The question is, will a 1.8 per cent price increase used to support smallholders to eliminate deforestation in the palm oil supply chain work? I’m not sure because much of the deforestation is still being done by companies, not by smallholders.

In August 2023, SPKS together with smallholders and Indigenous communities from several regions in Indonesia, and its supporting partners also launched the ‘Farmers For Forest Protection Foundation (4F)’ in Jakarta. The foundation is the only initiative formed by and for smallholder farmers in Indonesia. It is also the only initiative developed with the purpose of managing and channelling funding, managing programmes, and monitoring and reporting impacts, to support forest conservation and responsible deforestation-free practices and to improve the welfare of small farmers and local/indigenous communities, including compliance with the EUDR regulation. The 4F would be a good platform to channel funding to support deforestation-free smallholders.

There has been a lot of talk about working towards a ‘living wage’ for palm oil smallholders. However, an investigation by The Gecko Project last year highlighted flaws in “plasma” smallholder schemes which were billed as a way to lift local communities out of poverty but, according to the report, have excluded many smallholders from the earnings that were legally promised to them as part of the scheme. What is your assessment of the findings and what it tells us about smallholder inclusion in the palm oil economic growth story?

Several recent studies have found that the majority of smallholders in Indonesia live at or below the poverty line.

Studies conducted in Kalimantan, Sulawesi and Sumatra show that the net income of independent oil palm smallholders is around IDR 7 million (US$446) – IDR 12 million (US$765) per hectare per year. On average, both independent and plasma smallholders manage two hectares of oil palm or less. The income of both types of smallholders is also almost the same, but the total net income of independent smallholders may be higher because independent smallholders do not have to pay “management fees” – that is, interest and credit instalments for plantation establishment costs to the company. Most independent smallholders are also involved in other cash crop production, which adds to their income. However, even though their income appears to be relatively high, we must remember that according to 2018 data, the individual living wage in Indonesia is around IDR 1.5 million (US$97) per month.

Smallholder partnerships under “one-roof” management schemes run by oil palm companies need a complete overhaul. These schemes, which are frequently heralded as success stories by companies, are often not managed transparently and result in plantations with low production, according to smallholders. The schemes have failed to improve the welfare of smallholders, and to the contrary, some smallholders have lost their income and land, and this has often led to conflicts with communities.

We need to replace “one-roof” management schemes with “independent smallholder empowerment” schemes, overseen by the government and independent parties. These new schemes should be based on transparency, FPIC principles, participatory mapping for plantations and conservation areas, low-interest micro-credit to support setup costs, technology and knowledge transfer, stable long-term supply contracts, and direct purchase at fair prices.

Essentially, smallholders should be treated as partners in local businesses, not as objects or as labourers.

It will also be difficult for many smallholders to earn a decent income without supplementary income due to their small farm sizes and low productivity levels. Other employment opportunities may be needed by members of smallholder households. This is an opportunity for the government and companies to employ local labour, such as for nurseries or ecotourism to protect the surrounding customary forest.

One of the reasons why palm oil is cheap compared to other edible oils is because the wages of palm oil workers earn are so low. With that economic dynamic at play, is it realistic to expect large palm oil buyers as well as growers to pay smallholders a fairer wage?

I believe palm oil companies have no other choice now but to pay fair wages and prices.

Preamble Recital 50 of the EUDR states that “producers, particularly smallholders, should be paid a fair price for their products, so as to enable a living income and effectively address poverty as a root cause of deforestation.”

For consistency in global trade, due to market demand and to address climate change, rules similar to EUDR will soon be adopted by other countries. EUDR emphasises the importance of product traceability information to ensure that products are responsibly sourced. People who argue that market leakage is a loophole clearly do not understand that the global commodity supply chain network is an interconnected system that spans across countries and regions, and knows no political or geographical boundaries.

Soon, irresponsibly sourced products will be off the shelves worldwide.

What is your sense of what the priorities are for most independent smallholders in Indonesia right now, for instance a fair wage, the price of palm oil, sustainability or climate change?

Sustainability covers all those issues and is the priority among smallholders – especially as it is linked to increased productivity and improved livelihoods.

According to the World Bank, around 43 per cent of Indonesia’s population resides in rural areas and close to 29 per cent of the Indonesian workforce work in the agricultural sector. Around half of Indonesian farmers are smallholders. Primary agricultural production accounted for 13.7 per cent of GDP in 2020. Clearly, the sustainability and welfare of smallholders is important for Indonesia’s stability and economy.

Since 2020, Indonesia has launched and championed a national “food estate” programme, designed to counteract the “impending” global food security crisis. I strongly believe that instead of clearing forests and other ecosystems to develop new food estates, Indonesia should focus on empowering smallholders, treating them as national partners, increasing production, establishing agroforestry, providing fair prices, and helping them to implement more sustainable practices. Allocation of funds for food estates should be diverted to smallholders.