Recessions usually mean stalled economic growth, but small-scale solar projects in Asia could remain a bright spot, energy experts say, especially as the industry can be used to boost local economies.

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) said on new year’s day that a third of the world could go into recession in 2023, due to slowdowns in key markets of the United States, European Union and China. The forecast comes on the back of three bruising years for the global economy since 2020, first from the Covid-19 pandemic, and then Russia’s ongoing war in Ukraine – which also led to a rebound in pollutive coal power.

While the economic impacts could stifle the funds and manufacturing needed to sustain the growth of renewable energy capacity, policymakers could also start seeing smaller projects, such as local production and installation of rooftop solar panels, as lifelines for its domestic market, according to Henning Gloystein, director of energy, climate and resources at US-based consultancy Eurasia Group.

“You don’t need billions of dollars of investments for this. You can have community support systems in local towns and small grids, you can do quite a lot here,” Gloystein said.

“It saves [people] electricity costs, it gives local jobs to local companies,” he added.

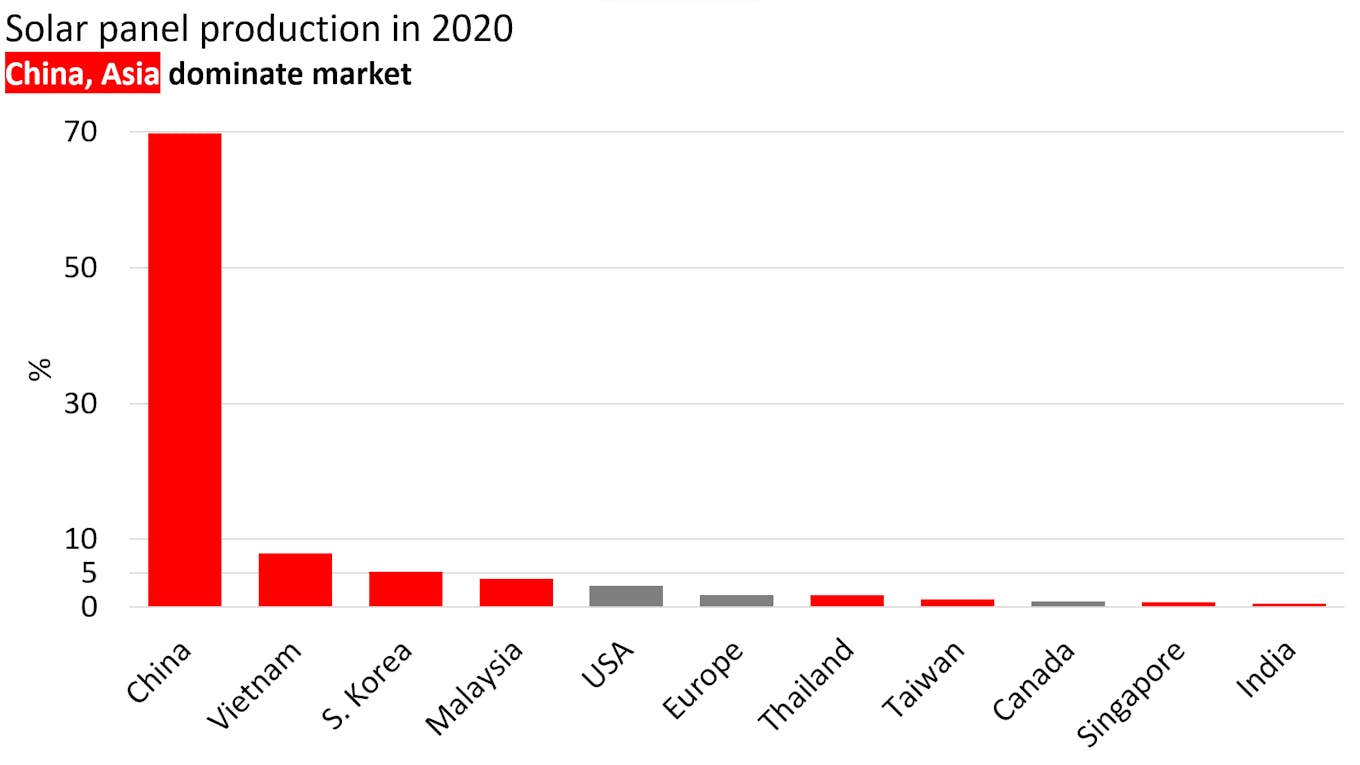

Ex-China Asia appears well-positioned to lead such a manufacturing rally, relative to other regions. China controls a steep 70 per cent of global solar panel production, but seven of the next 10 largest manufacturers – India, Malaysia, Singapore, South Korea, Taiwan, Thailand and Vietnam – are in Asia, according to a 2020 Statista count.

Data: Statista.

The preference for smaller renewables projects, if realised in 2023, would mirror similar trends seen over the past two years. Bloomberg reported that rooftop solar installations in China grew rapidly when high costs were stalling larger projects in 2021. Last year, the publication reported that European factories rushed to install rooftop panels after Russia invaded Ukraine and threatened the region’s gas supply.

Asia Pacific is already home to over half of the world’s solar panels found atop private homes, office blocks and factories, according to analytics firm GlobalData. Such projects are typically cheaper and less cumbersome than large, utility-scale projects that require dedicated land space. While solar farms usually feed electricity into a country’s power grid, power from rooftop panels can be used exclusively by the building owner, or even sold to grid operators.

The trend is likely to be helped by a favourable political environment for renewables as climate impacts intensify, along with volatile fossil fuel prices that mess with energy security, experts say.

Within Southeast Asia, archipelagic countries such as Indonesia and Philippines are paying particular attention to small-scale solar installations for their many island communities, especially since the price of solar panels has dropped sufficiently, said Muhammad Shidiq, a senior research analyst at the ASEAN Centre for Energy, a think tank.

Indonesia set a target in 2021 to install 3.6 gigawatts (GW) of rooftop solar panels by 2025, up from a low base of 60 megawatts in mid-2022, according to the German-Indonesian chamber of industry and commerce. Rooftop solar capacity in the Philippines was estimated at around 100 megawatts in 2021.

But projects will require more than headline aspirations to succeed.

“There are local building regulations, there are grid issues – how do you interconnect? Do you have a metering scheme, or some other credit system?” said Nicholas Wagner, programme officer for renewable energy roadmaps at the International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA), adding that considerations will vary even in different parts of one country.

“There is no doubt that [rooftop solar] has potential, and is a market that hopefully will grow substantially, but there needs to be both regulatory and policy support,” Wagner said.

There have been hiccups in Asia. US-based Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis found that India could be 60 per cent short of its 2022 rooftop solar power target of 40 gigawatts. Low consumer awareness, inconsistent policy frameworks and a lack of low-risk financing are to blame, the energy transition think tank said.

Vietnam, which has provided hefty subsidies for a large buildout of rooftop solar panels over the past few years, has struggled with power overload on sunny days, when huge amounts of electricity are generated but not needed. Stronger market regulations have been proposed by its state utility firm, Vietnam Electricity.

It also remains to be seen if domestic solar panel production in Asia can take off if China faces a manufacturing slowdown, since the country holds near-monopolies on the production of components like high-quality silicon and photovoltaic cells.

“For the first time in 40 years, China’s growth in 2022 is likely to be at or below global growth,” IMF managing director Kristalina Georgieva told CBS News in the US, adding that there could be “bushfire” Covid cases in the country for up to six months due to the abrupt ending of its pandemic restrictions. China’s manufacturing activity shrunk sharply in the last quarter of 2022 due to Covid-19 risks.

On the other hand, the supply of Chinese solar panel parts to Asia could increase since the US restricted such imports from China, said Pedro Vasconcelos, executive chairman of Singapore-based renewables firm EDPR Sunseap. The US had banned shipments from China’s Xinjiang region, which houses many of its solar panel factories, last year over fears of forced labour.

That, along with lower shipping prices, has resulted in a 3 to 6 per cent dip in logistics costs over the past two to three months, Vasconcelos said, adding that he expects the trend to continue in the “medium term”.

Vasconcelos added that the economic outlook for Asia remains better than Western markets, and if a recession does hit, EDPR Sunseap can provide the option to cover the cost of rooftop panel installations and charge a subscription fee for the electricity later – essentially spreading the upfront costs over a longer period.

Better data, planning

Renewable energy capacity in Asia has risen more than ten-fold in recent years, from about 75 GW in 2011 to over 870 GW last year, according to IRENA.

Upcoming policy developments in the region, such as a further opening up of corporate electricity deals in Vietnam, plans to increase foreign ownership limits for energy projects in the Philippines and China’s goal to transition towards a wholesale power market by 2030 could all boost the buildout of renewable capacity, Vasconcelos said.

“There is a huge movement going forward, with auctions coming, markets transitioning … it is an exciting time to be in all of these markets,” Vasconcelos said.

But increasing wealth and population in the region means that the use of fossil fuels is also rising in tandem. Eurasia Group’s Gloystein said he expects more work on reducing emissions in natural gas extraction, via the use of carbon capture technologies, which if successful could help policymakers justify the use of the fossil fuel for years to come.

Such initiatives have been championed by Japan, a major buyer of Asia Pacific gas. Japanese firms have signed deals with countries like Malaysia and Australia to work on carbon capture projects in recent years. Separately, Malaysia’s Petronas is developing what could be the biggest offshore carbon capture and storage project near one of its gas fields off Borneo island.

The scale of the energy challenge means that Southeast Asia should formulate its transition strategy as a region, to facilitate green investments and the development of a regional electricity grid, Gloystein added.

“Whether they [can] do it this year, I don’t know, but it will have to happen at some point,” Gloystein said.

Shidiq said better data on how energy policies impact the climate is needed to provide better guidance for the region – an effort he is part of at the ASEAN Centre for Energy this year.

IRENA’s Wagner added that governments need to stay the course on long-term energy transition targets, and accept that there will be “ups and downs” in the process.

“A very bad thing governments can do is to constantly change policy and introduce uncertainty into businesses and markets,” Wagner said.

“Even oil companies have said, we will do the transition, just give us a stable, long-term vision that we can work with, so that we can adjust our business plans,” he added.