The tension in the air was palpable in the final days of the Bonn Climate Change Conference (SB58), as negotiators struggled to find common ground on issues like climate mitigation and finance.

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

“Please, wake up,” said conference co-chair Nabeel Munir, from Pakistan, in a plenary session more than a week into the conference.

“What is happening around you is unbelievable,” Munir said, referring to the impacts of climate change across the globe.

Each year, climate negotiators come together in Bonn, Germany to prepare decisions to be adopted at the United Nations Conference of Parties (COP). This year, COP28 is set to take place in Dubai, United Arab Emirates at the end of the year, while the Bonn climate talks took place from 5-15 June. SB 58 is meant to be a more technical affair as it does not see the attendance of heads of states or fanfare of the event-packed pavilions featured in COP.

But negotiations were off to a shaky start from the get-go, with parties failing to even agree on the conference agenda.

“

We must reset the table. For climate policies to deliver just and effective action, the voices of those most impacted by climate harms and the fossil economy must be at the negotiating table.

Sébastien Duyck, campaign manager, Centre for International Environmental Law

A key point of tension was whether the Mitigation Work Programme (MWP)—which calls for urgently scaling up mitigation ambition and implementation—should be included in the agenda. The MWP was first established at COP26 in 2021, and at COP27 parties agreed that the mitigation programme should begin immediately.

However, some developing countries including the Arab States and Like Minded-Group of Developing Countries (LMDC) resisted the inclusion of MWP, calling for increased financing for adaptation and loss and damage. With no agreement in sight, parties decided to use a provisional agenda to guide discussions over the two week conference—a move observers say is highly unusual, as work is not normally launched prior to the adoption of the conference agenda.

Then on 7 June, two days into the conference, the LMDC group proposed the inclusion of a new agenda item to “urgently [scale] up financial support from developed country parties”. This was supported by the Arab group and Bolivarian Alliance for the Peoples of our America (ALBA), an intergovernmental organisation that supports the integration of Latin American and Caribbean countries.

“There can be no discussion on enhancing mitigation ambition … without an accompanied discussion on enhancing financial support ambition from developed countries,” wrote LMDC chair Diego Pacheco Balanza, from Bolivia, in the proposal.

Climate finance was a huge sticking point throughout the conference as many developing states and civil society representatives called on richer nations to “honour their financial pledges”. In 2009, developing countries committed to collectively mobilise US$100 billion per year by 2020 to support climate action in developing countries. This target has yet to be met. According to an OECD report, developed countries mobilised US$83.3 billion in 2020—primarily in the form of loans, which some say only add to the debt crisis faced by poorer countries.

The European Union, United States, New Zealand and others rejected the LMDC’s proposal, bringing discussions to a deadlock. According to youth delegate Cheryl Cadeline from Singapore, who attended the conference as a researcher, “the atmosphere in the last few days had a sense of ‘now or never’”.

“We could see negotiators literally lingering in the hallways looking stressed,” Cadeline said.

In an intense second plenary session on 12 June, co-chair Munir told delegates he felt like he was “conducting a primary school class”.

“I come from a country where [climate disasters] happened last year – 33 million people were impacted. A third of [Pakistan] underwater and I go back and tell my people that we were fighting for [an] agenda for two weeks? Come on, is it worth it?” Munir said.

Parties eventually reached a compromise on 14 June, adopting a watered-down agenda that left out the Mitigation Work Programme. Instead, discussions on the MWP that took place in Bonn based on the provisional agenda will be reflected in an informal note.

“The importance of the agenda cannot be overstated,” Melissa Low, a researcher at the NUS Centre for Nature-based Climate Solutions and an experienced COP delegate, told Eco-Business. “It allows for negotiations to take place and recommendations to be put forward at the SB58 session and taken to COP28.”

Conference outcomes

The conference saw some progress on specific work streams including the Global Stocktake (GST), which is a process for countries and stakeholders to track their progress—or lack thereof—towards meeting the goals of the Paris Agreement. The stocktake takes place every five years, with the first-ever stocktake scheduled to conclude at COP28 in December this year.

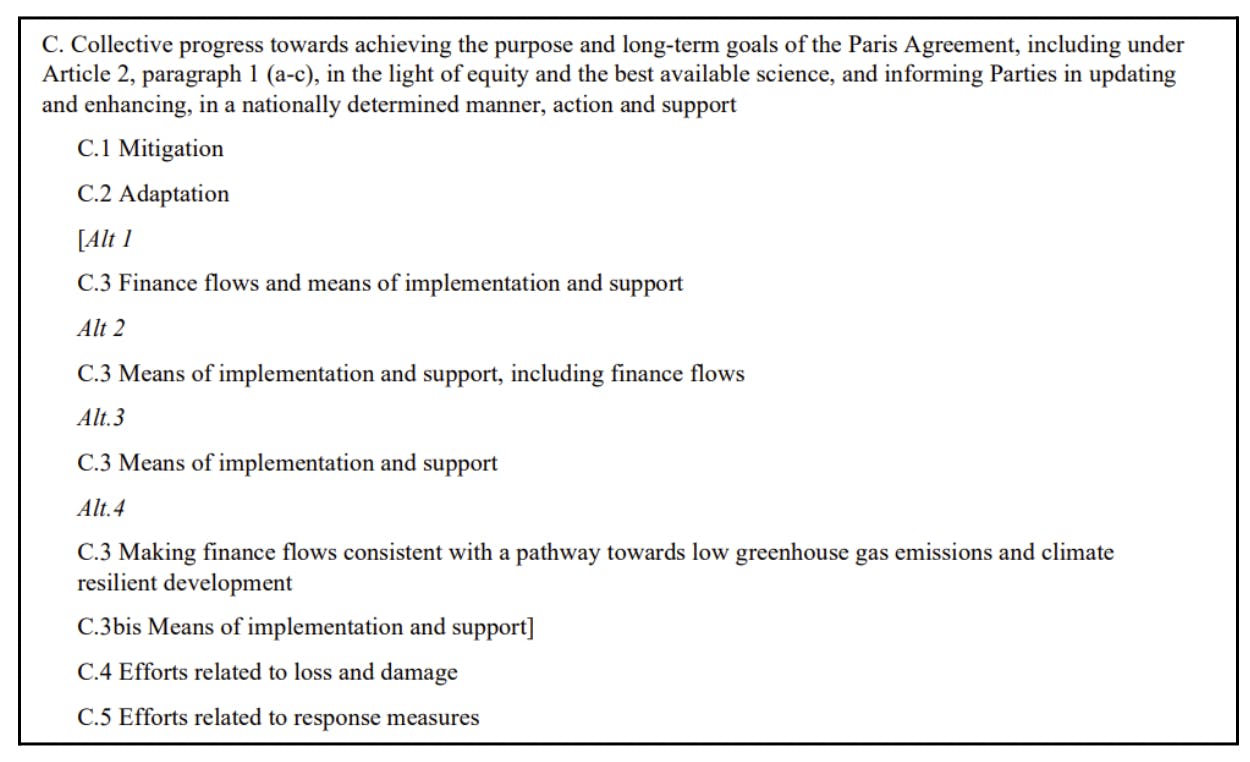

Screenshot of Section C of the GST draft text, with divergent phrasing options for finance [click to enlarge]

“GST provides an opportunity to collectively reflect on where the world stands in terms of addressing climate change,” Low said.

In Bonn, parties worked together to create a draft framework for the GST. Finance once again cast a shadow over discussions, with parties failing to agree on how much emphasis should be placed on the phrase “finance flows” in the text. The final draft included several options rather than agreed-upon wording.

Meanwhile, Low said that a key dialogue process on Loss and Damage at SB58 provided useful information to advance the work of the Transitional Committee—the body charged with operationalising the new loss and damage fund and funding arrangements. The Committee will be making recommendations for consideration and adoption at COP28.

Loss and damage was a key focus for civil society representatives present at the conference, who held numerous demonstrations both inside and out of the conference venue. Protestors called on countries to “fill the fund” and “make polluters pay”.

“All eyes are looking ahead to COP28 climate talks, in the hope of finalising a new fund to address loss and damage. The same crunchy questions around cash will need to be resolved if climate talks are to have a chance of really helping people on the front lines of the crisis,” said Teresa Anderson, ActionAid International’s Global Lead on Climate Justice, in a press statement.

Youth activists call for more urgent Loss and Damage funding. Image: Kate Yeo

Controversial COP28 President

SB58 also saw a brief appearance made by H.E. Dr. Sultan Ahmed al-Jaber, this year’s COP28 president. Al Jaber, who was appointed by the United Arab Emirates government—the COP28 host—is also the head of state-owned Abu Dhabi National Oil Company, which many campaigners say presents a clear conflict of interest.

In May, over 130 Capitol Hill Democrats and European parliament members sent a letter to top officials including President Biden and UN Secretary-General António Guterres, urging them to withdraw the appointment of al-Jaber. The authors called for immediate steps to limit the influence of polluting industries at climate conferences, “particularly major fossil fuel industry players whose business strategies lie at clear odds with the central goals of the Paris Agreement”.

But other prominent leaders have also come to al-Jaber’s defence, including US climate envoy John Kerry who earlier this year called him a “terrific choice”. At SB58, H.E. Shamma Al Mazrui, the UAE Minister of Community Development, said at a youth event, “What if oil industry leaders were actually the experts in leading this energy transition? … They know what needs to be done to make the energy transition a reality on the ground and not just rhetoric.”

Clara von Glasow, a representative of UN youth constituency YOUNGO, told al-Jaber at the same event: “Many people, including children and youth all over the world, are rightly concerned about your ties and links to the fossil fuel industry. This is your time to prove them wrong and show that indeed you are serious.”

Others, however, remain more sceptical. Sébastien Duyck, campaign manager at the Centre for International Environmental Law, a Geneva-based nonprofit, said: “The UN climate talks are going in the wrong direction, and we do not have time to waste. It is hard to imagine Sultan Al Jaber advancing an agenda for a full, fair, funded, and equitable fossil fuel phaseout and respect for human rights at COP.”

“We must reset the table. For climate policies to deliver just and effective action, the voices of those most impacted by climate harms and the fossil economy must be at the negotiating table,” said Duyck.