By 2030, poverty and hunger should be history, every human being should have access to clean energy, and the impacts of climate change should be reduced.

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

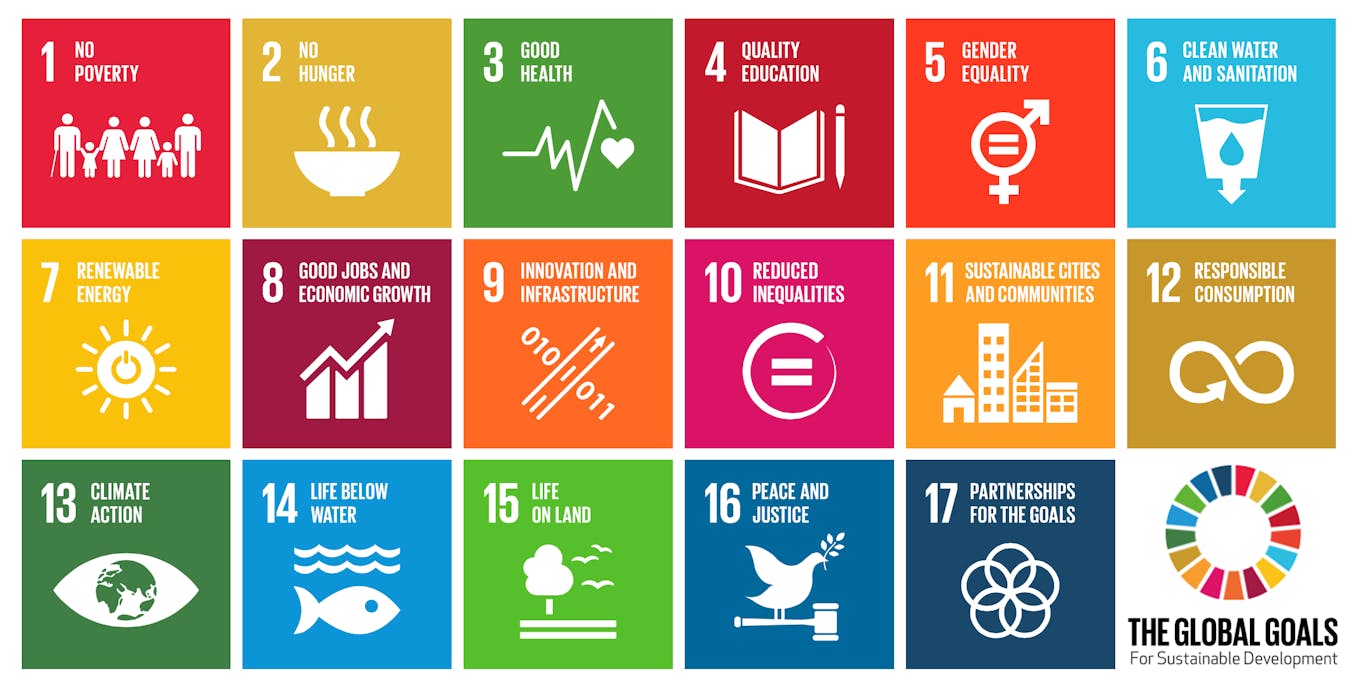

These are just three of the 17 promises the global community made last September when it adopted the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

The SDGs are a United Nations initiative to develop universal targets that balance the environmental, social, and economic aspects of development. They pick up where the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) left off, and form the cornerstone of the UN’s global development agenda till 2030.

The goals are more ambitious and far-reaching than their predecessor, and achieving them will be impossible without the private sector’s support, say global leaders.

UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon summed it up succinctly when he said at an event commemorating the SDG launch last year: “Governments must take the lead in living up to their pledges. At the same time, I am counting on the private sector to drive success.”

He added: “We would be closer to the world we want if companies everywhere took baseline actions like respecting employee rights; not polluting land, sea and air; and punishing corruption.”

The 17 Sustainable Development Goals. Image: Global Goals

The sheer scale and scope of the new goals make the private sector’s support even more crucial than ever.

While the MDGs were targeted mainly at developing nations, the SDGs apply to all countries.

And where the MDGs prioritised action on poverty, hunger and other basic issues, the new set of goals promote sustainable economic growth by taking on new concerns such as climate change, urbanisation, income inequality, and innovation in technology.

Not only is the private sector a major decision-maker in these areas, analysts say that its contributions are also essential for overcoming the US$2.5 trillion funding gap which sectors such as infrastructure, food security, climate action, health, and education are not able to get from governments.

Intertwined fates

Supporting the SDGs will yield rich returns for firms, say observers.

Thomas Milburn, senior consultant for Southeast Asia at sustainability advisory firm Corporate Citizenship, says that “the case is clear for companies to get involved by doing business responsibly and pursuing opportunities to solve global challenges”.

For one thing, companies which offer affordable solutions to climate, health, and other SDG-linked concerns can generate new markets for their innovative products and services.

Since governments around the world have committed to adopting the goals, companies can also expect future policy decisions and legislation to be tailored towards meeting those aims, he adds.

“Businesses which are aligned with this are more likely to maintain their public licence to operate,” says Milburn.

“

The SDGs can’t be addressed by individual efforts of any one organisation. Companies should seek out strategic partners to help them achieve the goals.

Thomas Milburn, senior consultant for Southeast Asia, Corporate Citizenship

Firms are increasingly cottoning on to this. As global consultancy PwC found through a recent global survey of almost 1,000 businesses, more than 71 per cent of the companies polled said they are planning how to work towards the SDGs.

The three SDGs which businesses felt most prepared to tackle were decent work and economic growth, climate action, and boosting industry, innovation and infrastructure.

The survey also polled 2,015 citizens worldwide, 90 per cent of whom said that businesses should sign up to the SDGs. Some 78 per cent of respondents said they were more likely to buy from companies which have done so.

However, the private sector is currently falling short when it comes to translating their commitments to action.

Only 41 per cent of corporate respondents said they will embed the SDGs into their core business strategy over the next five years, and a mere 13 per cent know what tools they need to measure progress against the goals.

Bridging this gap is a long and complex process and PwC suggests that companies should start by identifying which SDGs their operations have an impact on. They should then settle on a methodology to measure their impacts on each goal.

While there is no universal framework to track progress against the SDGs yet, companies can devise their own, or draw upon toolkits being developed by organisations such as the UN Global Compact and Global Reporting Initiative.

When developing a strategy to minimise their negative impacts and maximise benefits, firms should also take into account which SDG-related outcomes the government in their region has prioritised, and as far as possible, prioritise delivering solutions which help meet the needs identified by governments.

This alignment between business and public sector priorities protects a company’s license to operate and improves its long-term resilience, says PwC.

Before an action plan can be incorporated into wider business strategies, companies must set quantifiable targets for each measure. This also aids in the final step of the process: measuring and proving progress, and communicating it to stakeholders.

Corporate Citizenship’s Milburn adds that collaboration with other companies, non-profits, and public sector partners is the key to a successful SDG effort.

“The SDGs can’t be addressed by individual efforts of any one organisation,” he says. “Companies should seek out strategic partners to help them achieve the goals”.

Growing private sector recognition of the importance of supporting the SDGs has given rise to business coalitions such as Impact for 2030 - a corporate volunteering initiative, and the Business and Sustainable Development Commission, which brings together public, private, and people-sector leaders to advance the SDGs.

One major initiative is Business for 2030, launched last September by the New York-based United States Council for International Business (USCIB). The programme showcases efforts by companies worldwide to contribute to the SDGs, and aims to foster partnerships between the public and private sectors to meet the goals.

Ariel Meyerstein, USCIB’s vice-president of labour affairs, corporate responsibility and governance, recalls that in 2014, the organisation recognised that the SDGs offered an unprecedented space for the private sector to participate in the global development agenda.

“This meant that businesses needed to quickly get up to speed on this vast, ambitious, and dizzying new framework,” he says. “Business for 2030 provides a public resource that helps translate existing and ongoing corporate activities into the new SDG language.”

This collection of concrete examples not only offers other businesses case studies on how to get involved, but also allows governments to identify good corporate initiatives in their own countries, which they can then collaborate with, explains Meyerstein.

The site today hosts more than 140 initiatives from 35 firms which are implemented across 150 countries.

SDGs in action

Anglo-Dutch consumer goods giant Unilever has, over the years, emerged as one of the most vocal and prominent corporate supporters of the SDGs.

Not only did Unilever chief executive Paul Polman serve on the UN’s consultation committee to decide the goals, he also co-founded the Business and Sustainable Development Commission with former UN Deputy Secretary-General Lord Mark Malloch-Brown.

David Kiu, Unilever’s vice-president of sustainable business and communication, shares that the company hopes to help achieve a ‘zero carbon, zero poverty’ world, and “strongly believes that a sustainable business model is the only viable business model”.

Unilever’s progress on the SDGs is consolidated in its Sustainable Living Plan, which lays out quantifiable targets relating to environmental protection, promoting health and well-being, and enhancing livelihoods.

Among these are a promise to source 100 per cent of its agricultural commodities sustainably by 2020, and enhancing the livelihoods of a million people across their supply chain by the same year.

Kiu shares that three of the SDGs which Unilever has been especially proactive on are ending hunger, ensuring sustainable water management and sanitation, and promoting responsible consumption and production patterns.

The company dubs the products which advance these goals ‘Sustainable Living Brands’. Among these are Comfort One Rinse, a fabric softener which requires 75 per cent less water for laundry than other products. This fuels Unilever’s work on the water-related SDG.

Food brand Knorr has also committed to sustainable sourcing of its vegetables and produce, and to roll out more products which meet the highest nutritional standards.

In addition to its own products, Unilever also works with partners from all sectors to make progress on the SDGs, says Kiu.

For example, the Comfort One Rinse team worked with Vietnam’s Ministry of Natural Resources to educate consumers on the detergent’s water-saving properties, while the company partnered with the Vietnam Women’s Union to provide households with cheap water filters that require no energy to operate.

These efforts to align business operations with the SDGs has paid off, says Kiu.

“Our sustainable living brands are growing 30 per cent faster than the rest of our business,” he says. “They delivered nearly half our total growth in 2015, and are creating movements for change.”

“

If businesses don’t actively participate in what is seen as the solution — that is, the SDG’s policy recommendations — they will increasingly be seen only as part of the problem.

Ariel Meyerstein, vice-president of labour affairs, corporate responsibility and governance, United States Council for International Business

Towards a sustainable business agenda

As more companies and policymakers work to support the sustainable development agenda, there are numerous challenges that need to be addressed.

The greatest of these, says USCIB’s Meyerstein, is good governance and infrastructure.

The Sustainable Development Goals projectedc on the United Nations headquarters in New York. Image: UN Photos, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

Regulations such as strong intellectual property frameworks, labour standards, and solid health and transport infrastructure are essential for companies to develop and disseminate sustainable technologies across the world, he explains.

“Businesses can neither create the policy frameworks nor implement them, but they desperately need them to be in place to operate,” he says, adding that strong policy support is crucial to give businesses the conducive environment they need.

Singapore is a good example of “what is possible when you tackle governance deficits head-on”, Meyerstein says, praising the country’s anti-corruption efforts, education and health systems, and its efforts to create an enabling policy environment for businesses.

Corporate Citizenship’s Milburn adds that in Asia, most local firms are still trying to understand what the SDGs mean to their business, and governments can also play a key role in addressing this.

Putting the SDGs at the heart of local and national-level development plans and communicating this clearly will sends a policy message that resonates with business communities, he says. It will also set a clear direction for them to follow suit.

For Meyerstein, companies which ignore the sustainable development agenda do so at their own peril.

“Business is increasingly looked to by other stakeholders as both a contributor and a potential solution to the problem of inequality,” he notes. “If they don’t actively participate in what is seen as the solution — that is, the SDG’s policy recommendations — they will increasingly be seen only as part of the problem.”

This story was first published on Future Ready Singapore. Click here to subscribe to the newsletter.