Solar power systems are generally said to last about 25 to 30 years. But here’s a less widely known fact: Although their power capacities may dip by about 20 per cent over the course of a quarter-century, there is still potential to deploy them in regions starved of electricity supply, where they can be used for another 10 to 20 years.

This extension of their useful lives has implications for a world staring at a ticking solar time bomb.

Solar uptake is growing amid the need for zero-emission energy sources to fight climate change, but the flip side of the coin is an impending flood of decommissioned panels in the coming years, Eco-Business reported recently.

According to the International Renewable Energy Agency, the world could be saddled with 78 million tonnes of solar panel waste by 2050—more than 8,500 times the weight of the Eiffel tower in Paris. The problem is especially acute in Asia, where solar markets are expanding faster than anywhere in the world.

Like other industries, solar needs to go circular.

“The industry must address its waste problem by reducing, reusing and recycling materials,” said Vivek Chaturvedi, regional business director for solar in India, the Middle East and Africa at Royal DSM, a Dutch multinational that deals in health, nutrition and sustainable living.

“Solar panels degrade but by the end of their lifetime, they still perform at 80 per cent of their original capacity. That’s still enough to use in home lighting systems or microgrids, rather than incinerate or recycle them right away,” Chaturvedi said. “The quality of materials used in panels today should be such that they can live a second life and make an impact for another 10 to 20 years.”

“

The industry must make recycling-friendly designs a key concern.

Shahariar Chowdhury, research fellow, Faculty of Environmental Management, Prince of Songkla University, Thailand

Making reuse a priority

When panels need to be decommissioned, some components may still be suitable for reuse. Such parts could be channelled straight back into the production process, cutting manufacturers’ energy and raw material needs, said Clive Fleming, director at Australian company Reclaim PV Recycling.

For instance, if a module’s protective glass sheets can be extracted intact, they can be refined rather than reprocessed, while the electrical contacts printed on power-generating silicon wafers can be stripped off and reprinted, enabling panel producers to reuse silicon cells, he said.

More research is needed to explore ways to shrink waste streams, Fleming added.

Design with recycling in mind

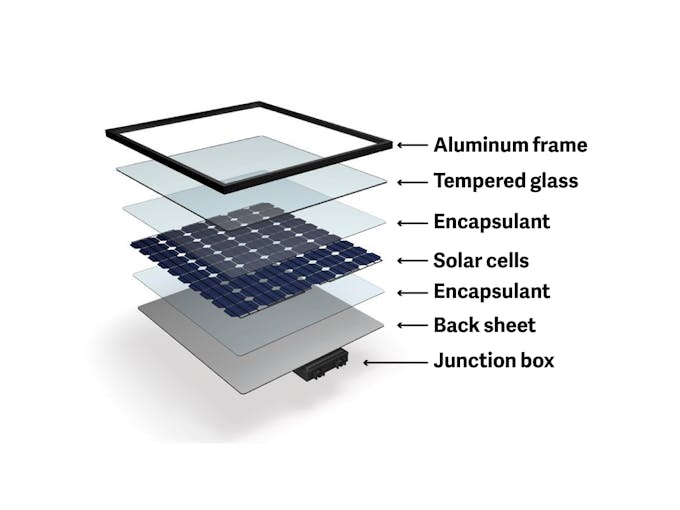

Solar panels aren’t easy to recycle. Photovoltaic modules are a medley of components such as stabilising aluminium framing, power-transmitting wires, protective glass sheets and polymeric membranes, as well as electricity-generating silicon wafers and other metals.

Recycling involves mechanical, thermal and chemical processes, making it tedious and expensive.

Virgin materials are, in fact, often cheaper than recovered ones. Recycling also exacts a toll on the environment, as it consumes vast amounts of energy and can generate toxic dust or other chemical by-products that are difficult to treat.

Although material choices made today will have ramifications on waste treatment 25 years down the road, few solar companies have taken recyclability into consideration in their panel designs. This needs to change, said Shahariar Chowdhury, a research fellow at the Faculty of Environmental Management at Prince of Songkla University in Thailand.

“The industry must make recycling-friendly designs a key concern,” he told Eco-Business.

“The focus of manufacturers, rightly, has been to reduce costs and ramp up efficiency to reach grid parity with fossil fuels. Now that this has been achieved in many parts of the world, considerations around waste are going to take a front seat globally in the coming years,” said DSM’s Chaturvedi.

Some panel producers have already realised the need to quit using toxic materials such as lead, antimony, fluoropolymers, and other similar materials in their products, he noted.

Parts of a silicon-based solar module. Image: Eco-Business

DSM has also come up with a protective backsheet for the base of solar panels that, unlike most conventional polymeric membranes, can be completely recycled.

Today, almost all components of solar panels can technically be recovered, but the transparent membranes that encapsulate solar cells to insulate and shield them from the elements continue to give recyclers headaches, Chaturvedi said.

Since most backsheets are laminated using adhesives, they cannot be remelted and reprocessed into new plastic products. The same is true for the encapsulant films that “glue” the backsheet, silicon cells and glass together. Together, backsheets and encapsulant films comprise up to 15 per cent of a module’s total weight.

Adding to this are the toxic gases that most films sold today, which contain weather-durable fluoropolymers, generate when burned. Disposing of them responsibly requires special incinerators that capture pollutants, which raises the cost of end-of-life treatment.

“Aluminium frames can be ripped apart and recycled. Glass can be shattered and melted again. Silicon can also be recovered, although it is currently more expensive than using virgin materials. But the polymeric encapsulants and backsheets that have traditionally been used are non-recyclable,” Chaturvedi said.

Instead of laminating its backsheets, DSM presses various thermoplastic films together in a process called coextrusion. Without adhesive layers and polluting fluoropolymers, they can eventually be processed into new plastic products, he said.

“

Now that grid parity has been achieved in many parts of the world, considerations around waste are going to take a front seat globally in the coming years.

Vivek Chaturvedi, regional business director, solar, India, Middle East and Africa, Royal DSM

Laws, infrastructure and knowledge sharing

The solar recycling industry is still nascent. Available recycling infrastructure is currently inadequate and government support that could boost recyclers’ efforts is lacking.

Because logistics are costly—silicon-based solar panels weigh between 20 and 24kg—decentralised recycling is the way forward, said Chaturvedi. Ripping bulky modules apart where they are installed reduces their volume, bringing down transport costs.

Logistics are a challenge that Reclaim PV Recycling is familiar with. In South Australia, the recycling firm opened the nation’s first commercial solar recycling plant last year and has to transport the panels collected from around Australia to the facility.

As the amounts collected increase, more infrastructure will be needed, Fleming said. The firm recently signed a lease for another facility in Brisbane that will ease logistical stress.

“

There is a whole bunch of information out there that needs to be shared among industry players, such that greener products are made from the beginning to enable better and less energy-intensive recycling.

Clive Fleming, director, Reclaim PV Recycling

For the circular economy to take off, industry players said rules must be put in place to mandate the recycling of solar panels.

Except for the European Union (EU), no country in the world has passed laws on solar waste recycling. In the absence of clear regulations, Chaturvedi said there is much ambiguity around where responsibilities for recycling should lie.

“Many states have implemented guidelines for solar recycling, but they are often not taken seriously. Focus is still on manufacturers to address this issue. However, the responsibility must be shared by all players along the value chain, including downstream players in engineering, procurement and construction, as well as developers in charge of maintenance and operations in many markets who know when panels degrade and need replacing,” he said.

Many manufacturers still refuse to recycle because of the cost involved, Fleming said. “There is a misconception that recycling solar panels should be offered free of charge. But the truth is, it is a costly enterprise to set up, and manufacturers do not have the budget for that yet,” he said.

If manufacturers are mandated to handle decommissioned panels responsibly, they would start incorporating recycling costs into their sales, while recycling laws would help to increase the amount of solar waste fed to recycling facilities, allowing them to scale up operations and reach the critical mass needed to reduce costs.

For solutions to become reality, better knowledge sharing and greater collaboration, particularly between recyclers and manufacturers, are needed, said Fleming.

Feedback on recycling outcomes could help manufacturers come up with better designs, while lessons on transport, installation and maintenance could be shared across the industry to prevent early faults and physical damage due to mishandling, he said.

“There is a whole bunch of information out there that needs to be shared among industry players, such that greener products are made from the beginning to enable better and less energy-intensive recycling,” Fleming added.

To this end, Reclaim PV Recycling is setting up a global database on solar panel materials and their recyclability that will be accessible by manufacturers, developers and recyclers alike.

“For a recycling business, it is crucial to know what is going into the recycling process. Only with that knowledge can we analyse results, give that information back to manufacturers and delve into ways to improve recycling together,” said Fleming.

Chaturvedi agreed that recycling policies will only bear fruit if responsibilities are spelled out for various players in the industry.

“That conversation needs to start today, or this situation will become even more difficult than it already is,” he said.