Sourcing the finance for climate adaption and mitigation efforts will be one of the biggest challenges faced by disaster-prone countries in forging a new agreement at key United Nations climate talks in November.

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

Poor countries were promised US$100 billion a year in climate finance by 2020 by developed country governments more than a decade ago. But rich countries will continue to miss the longstanding pledge to US$100 billion a year for the next four years, according to analysis by Oxfam International on Monday.

Data from the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) on Friday showed that climate finance reached only US$80 billion in 2019. Data was not available for 2020, but the US$100 billion target is likely to be missed amid the economic damage wreaked by the pandemic. Oxfam last year revealed the true value of financing is US$22 billion—only a quarter of what developed countries had reported.

Ahead of the 26th Conference of Parties (COP) in Glasgow, Scotland, negotiating blocs from developing countries have called the shortfall an “emotive issue” within the climate talks, that “damages trust” among parties.

“Issues identified include shortfalls in delivery, opaqueness of accounting by donors, problems with access, and the increasing presence of loans in the portfolio. These are in addition to the meagre resources allocated to adaptation,” read a position paper released in July by think-tank Powershift Africa, backed by the Climate Vulnerable Forum, Least Developed Countries, and the Alliance of Small Island States.

Climate negotiators from the least developed nations have pushed back against the majority of pledged finance being given as loans, with only 20 per cent awarded as grants, adding to the debt-burden of poor nations whose economies have buckled under the pressure of the Covid-19 pandemic. This is likely to be a point of contension at the talks in November, according to one negotiator.

With 40 days to go before the climate summit, Eco-Business explores what at-risk low-income countries have to grapple with in order to access the financing promised to help protect them against the worst impacts of climate change.

1. Why do developed countries need to pledge climate funding for poorer nations?

As the greatest contributor to the climate crisis, developed countries are expected to take the lead in the mobilisation of funds needed to address climate change, based on the principle of the common but differentiated responsibility (CBDR) under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC).

The CBDR is a principle of international environmental establishing that all states are responsible for addressing global environmental destruction yet not equally responsible.

At the UN climate summit in Copenhagen, Denmark in 2009, all developed countries agreed to provide US$100 billion in public and private finance each year by 2020 and through to 2025 to help developing nations tackle climate change.

2. How does climate funding reach recipient countries?

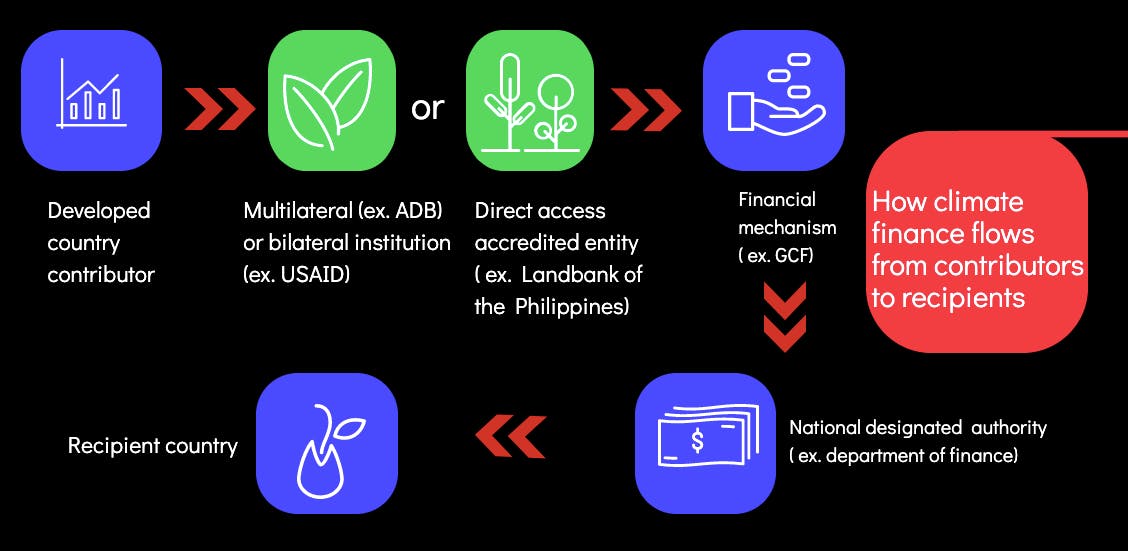

Contributor countries usually channel the funding for developing countries either through multilateral institutions or direct access accredited agencies which mobilise climate finance in a country.

In the international access modality, financial resources are managed by multilateral agencies like the Asian Development Bank (ADB), World Bank, European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, or bilateral institutions like United States Agency for International Development (USAID), Japan International Cooperation Agency, among others.

The direct access modality allows recipient countries to access funding through their national institutions, exerting stronger ownership.

All developing country parties to the UNFCCC are eligible to receive climate funding through any of its five financial mechanisms: the Global Environment Facility (GEF) which manages the Special Climate Change Fund (SCCF) and the Least Developed Countries Fund (LDCF), Adaptation Fund (AF) and the Green Climate Fund (GCF).

Compared to other bilateral and multilateral institutions that commonly operate as banking institutions aimed at making profit out of climate funds, the five funds under the UNFCCC recognise the CBDR principle and implement projects based on the outcomes and agreements of the COP.

The Green Climate Fund is considered the official financial mechanism for climate change, specifically created in 2010 with the vision to be the largest pot of climate funding available to developing countries.

Headquartered in South Korea, the GCF is meant to finance the adaptation and mitigation needs of poorer nations with annual pooled contributions from developed countries from the UNFCCC totalling a minimum of US$100 billion starting in 2020.

Eligible countries submit to the GCF their funding proposal through their National Designated Authorities (NDAs), which are assigned by the government to serve as the gatekeeper in accessing and receiving funds in a country. Recipients can receive GCF funding through direct access accredited agencies instead of multilateral institutions.

For instance, climate-vulnerable Philippines has two direct access accredited entities: Land Bank of the Philippines and the Development Bank of the Philippines.

“

What is especially tedious for proponents is the lengthy process from project origination to submission of the full package funding proposal, which takes a period of at least one to two years, now even more in light of restrictions from the pandemic.

Rachel Herrera, commissioner, Climate Commission of the Philippines

Developing country proposals include their country programmes, which outline their climate change priority areas for both adaptation and mitigation, and the budget to support them.

The submitted funding proposals undergo a thorough assessment based on GCF standards and principles, and are to be approved by its 24-member board.

The GCF provides “readiness support” in form of grants and technical assistance to the country’s NDA to prepare it for efficiently engaging with funding body, like the development of guidelines and procedure for screening and selection of national implementing entities for direct access to GCF and development of full funding proposals to GCF.

Carrying out the readiness support programme may be done by the NDAs themselves or they can hire third party consultants to implement the capacity building activities for various stakeholders like relevant government institutions, academe, civil society, among others.

3. What are the main setbacks to receiving climate funding?

A long and stringent process to get approval for a single project is the main cause for the slow pace of funding, said Rachel Herrera, commissioner of the Climate Commission of the Philippines, which was the country’s NDA for five years before the department of finance took over this year.

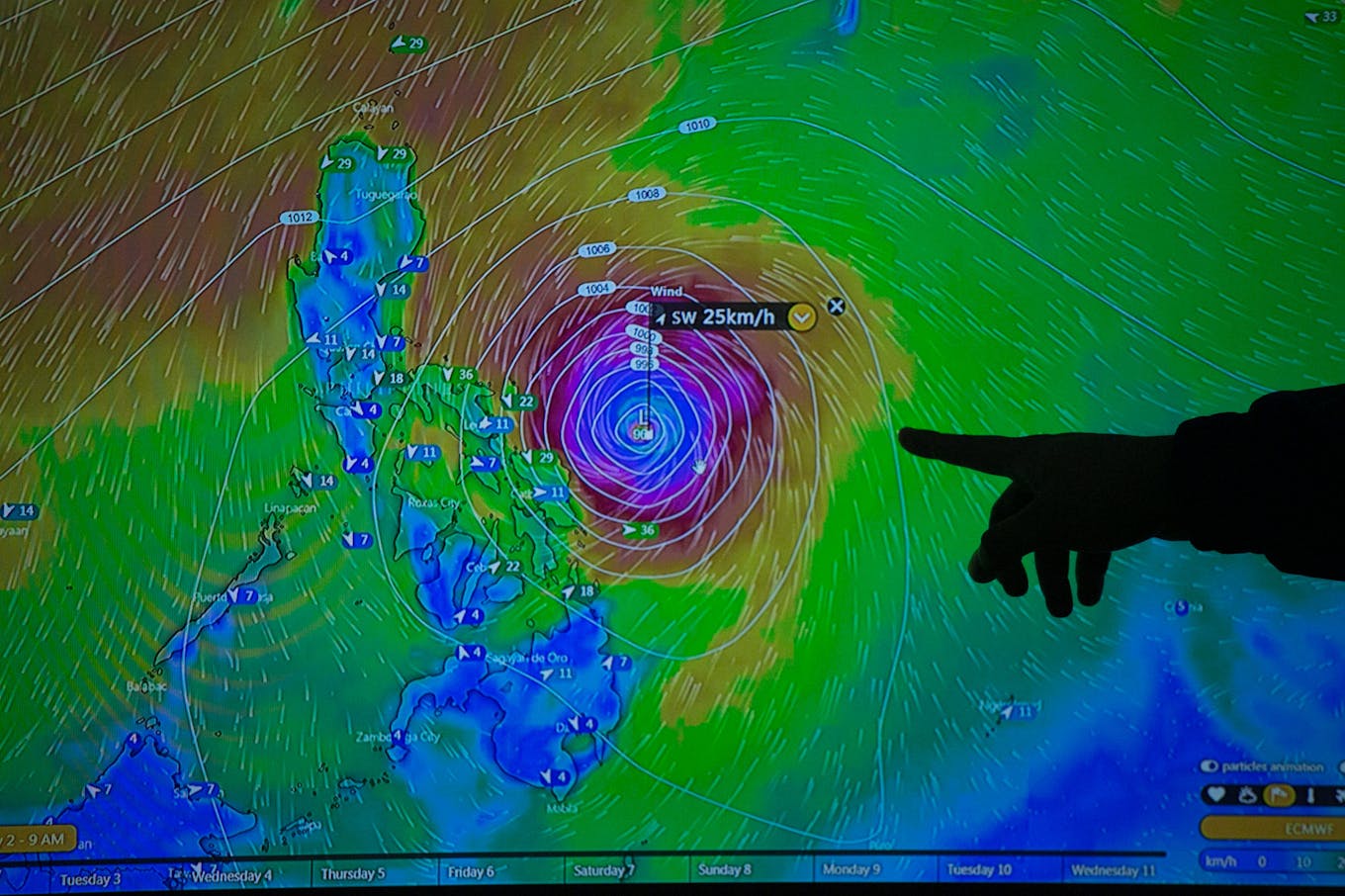

The Philippines, for instance, secured a US$10 million grant from the GCF in 2019 to establish a multi-hazard and impact-based forecasting and early warning system in four typhoon-prone areas in the country to assist local government units in implementing appropriate early responses to hazard alerts. It took nine months for the project to be approved from the time the proposal was submitted, but developing the full funding proposal took much longer.

“What is especially tedious for proponents, including country implementing agencies and the NDA working together, is the lengthy process from project origination to forming a viable concept note, towards submission of the full package funding proposal, which takes a period of at least one to two years, now even more in light of restrictions from the pandemic,” Herrera told Eco-Business.

The track of Typhoon Kammuri on a TV screen inside the City Disaster Risk Reduction Management Office in the city of Legazpi in Albay, Philippines on 2 December 2019. The city is one of the target sites of the country’s impact-based forecast and warning system that will receive partial funding from the Green Climate Fund (GCF). Image Greenpeace Philippines/ Basilio Sepe

In accessing the GCF, countries have to go back and forth with the body’s secretariat to meet its investment criteria, which includes the project’s lifetime emission reductions, its alignment with the country’s nationally determined contributions, how environmental and social safeguards and gender equality are an integral part of the project, among others.

Apart from the GCF, the recipient has to face additional procedures internally like following government protocol to ensure it does not express any objection to the proposals, said Herrera.

“One of the issues thrown at the GCF is its lack of flexibility to cater to the urgent needs of developing countries, especially in financing grants for adaptation projects and in accrediting state actors as the GCF’s local partners,” she said.

Furthermore, she noted that once a project proposal is finally approved, the country does not automatically receive the entire project funding. There are still certain conditions or milestones before cash is disbursed while the GCF works with accredited partners to channel these funds, requiring more time to discuss certain legalities and arrangements between the GCF and its partner entities.

The lack of frequency in GCF Board Meetings, which only take place three times a year, also contributes to bottlenecks, added Herrera. “The entire process of accessing the GCF then becomes a competition among developing countries on who quickly gets to take the first few slices of the climate finance pie,” she said.

“

Failure to deliver on adequate climate finance will mean failure in achieving climate goals. While impacts are greater for peoples of the South, wealthy nations and their peoples are and will be suffering the consequences, too.

Lidy Nacpil, coordinator of the Asian Peoples’ Movement on Debt and Development

4. What is the criteria of climate funders?

Each climate fund has certain priorities—mitigation, adaptation, and specific sectors.

For the GCF, its main priorities include projects which demonstrate low-emission energy access and power generation, low-emission transport, energy efficient buildings, cities and industries, sustainable land use and forest management, among others.

The GCF wants to ensure that developing country partners exercise ownership of climate change funding and integrate it within their own national action plans, which is why a NDA is a crucial focal point that acts as an interface between a nation’s government and GCF.

All GCF projects need to receive the approval of the NDA through a formal no-objection letter before being deployed within a country. The country-driven approach adopted by GCF aims to ensure that the fund’s activities are guided by national priorities, such as those expressed in national planning documents.

The GCF’s allocation framework aims for a 50:50 balance between mitigation and adaptation investments over time in grant equivalent terms. It intends to reserve half of the adaptation allocation to particularly vulnerable countries, including least developng countries, small island developing states and African States.

Gender expertise is another criteria for the accreditation, where funding proposals must have gender documentation during the project cycle.

It also has a formal Indigenous Peoples Policy, which recognises the right of Indigenous Peoples to free, prior and informed consent for all programmes affecting them or their territories, and aims to assist GCF in incorporating considerations related to Indigenous Peoples into its decision-making.

5. Why has the pledged US$100 billion not been fully mobilised yet?

A research paper released last week by HSBC suggested that the climate fund has not been fully mobilised because the collective agreement made in 2009 had no details on how it would be met or how each country would contribute.

“In the ensuing years, there has been austerity, such that developed countries have not provided funding to the levels required. There is also no clear and agreed definition of what climate finance is, so it is open to interpretation,” said Wai-Shin Chan, global head of Environmental, Social, and Governance research at HSBC.

However, climate finance advocates claim it is nothing more than the developed countries’ lack of commitment that is to blame for the unmet pledge, especially since their invesment in fossil fuels is several times more than their expenditure to meet net-zero targets.

“Climate finance is not only for covering the costs loss and damage in developing countries. It is also for fulfilling the fair shares of wealthy nations in mitigation actions so the world can reach real zero by 2050,” said Lidy Nacpil, coordinator of the Asian Peoples’ Movement on Debt and Development (APMDD), a regional alliance of peoples’ movements, community organisations, coalitions, and non-government organisations.

“Failure to deliver on adequate climate finance will mean failure in achieving these goals. While impacts are greater for peoples of the South, wealthy nations and their peoples are and will be suffering the consequences, too,” she said.