When park ranger Allan Daganta travels to work from his home in a village just outside Palawan’s Puerto Princesa Subterranean River National Park (PPSRNP), he’s usually welcomed by a cool forest breeze. That, he says, has changed since Dec. 17, 2021, when Super Typhoon Rai hit Palawan, turning the park’s once thriving forest from green to brown.

“Now, every time I drive to work I can feel the hot weather,” Daganta told Mongabay a month after the catastrophic storm, known in the Philippines as Typhoon Odette, struck the island. “I was born and raised here and in my 51 years of existence, it’s so far the strongest typhoon to ever ravage the park.”

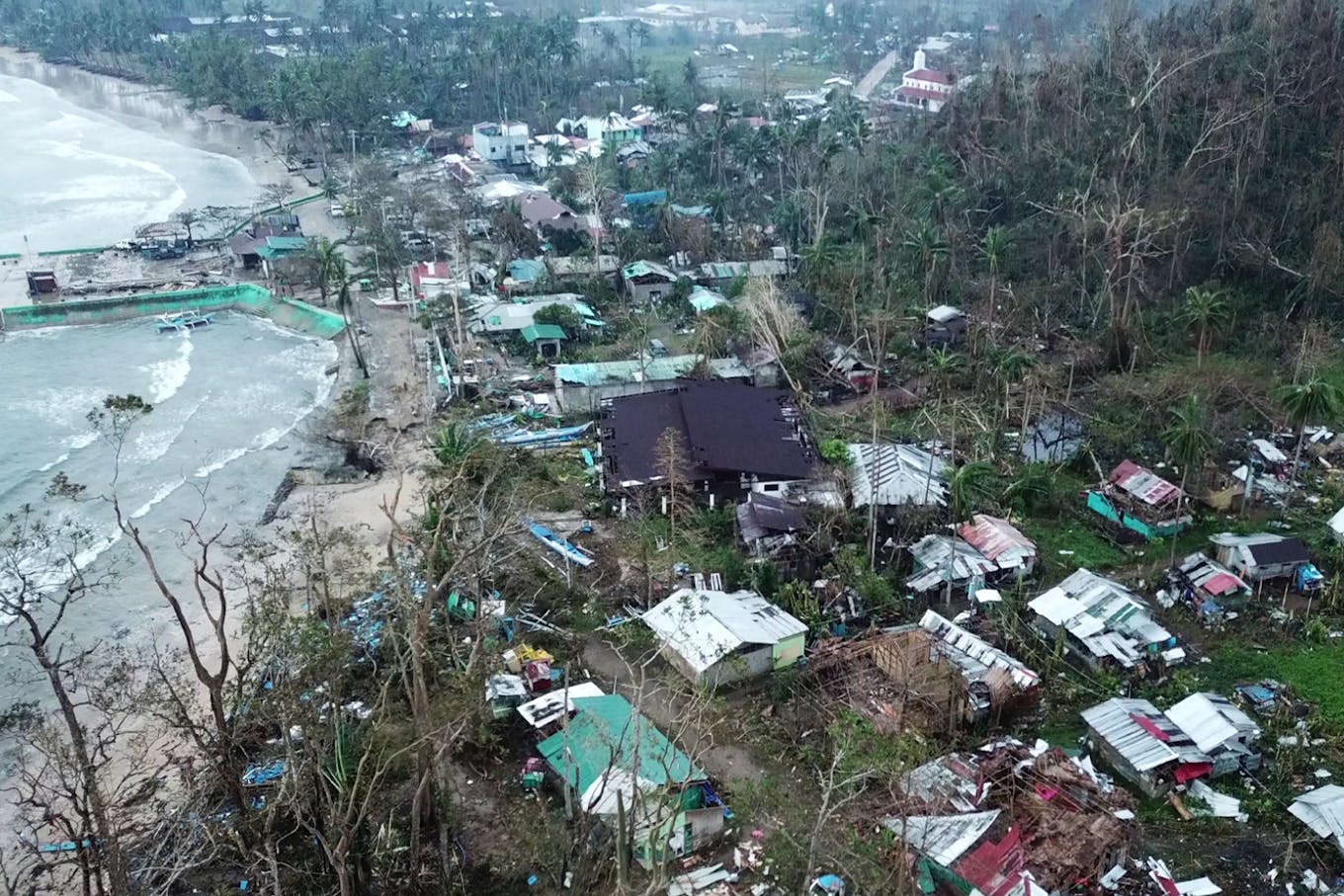

On duty a few hours ahead of the storm’s ninth and final landfall over northern Palawan, Daganta left the ranger station to seek safety at a colleague’s house. Shortly before noon, the park started to feel Rai’s ire. The howling wind toppled trees and flattened houses and park buildings, and the sea raged, swallowing up patrol and fishing boats anchored on the shore.

“During its onslaught, all I can exclaim was, ‘Oh, God, let this storm pass by,’” Daganta said. “The next day, fallen trees made roads impassable. When I returned to the station, its galvanised iron roof was torn down and all you can see inside were fallen tree branches.”

Puerto Princesa Subterranean River National Park (PPSRNP). Image: Sophia Lucero via Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

At the forest edges alone, at least 2,200 trees, including many century-old native dipterocarps, were damaged, based on park management’s initial estimates. The full extent of forest destruction left by Rai in the 22,202-hectare (54,862-acre) PPSRNP remains unknown; fallen trees have obstructed trails into the forest’s interior, hampering ground assessment.

The strongest storm to hit Philippines in 2021, Rai dismantled numerous park facilities and villagers’ homes, displacing more than 3,500 families a week before Christmas. It also destroyed 86 boats, once mainly servicing tourists but converted for fishing since the start of the Covid-19 pandemic. No casualties were recorded at the park, but the death toll across the Philippines reached 407, including at least 22 in Palawan.

The impact on wildlife has yet to be calculated.

PPSRNP is a UNESCO World Heritage and Ramsar site known for its impressive cave system and intact old-growth forests. The IUCN notes that it’s home to a large number of bird species, including the endemic Palawan hornbill (Anthracoceros marchei), Palawan peacock pheasant (Polyplectron napoleonis) and Philippine cockatoo (Cacatua haematuropygia), all of them threatened species. Wildlife law enforcement initiatives afford protection to commonly traded endemic mammal species taking refuge here, such as the Palawan pangolin (Manis culionensis), porcupine (Hystrix pumila) and bearcat (Arctictis binturong).

“It’s heartbreaking to see the devastation that the typhoon caused, not only to the forest, but to the wildlife as well,” park biologist Nevong Puna told Mongabay. “The adverse effect was huge, especially to birds depending on the canopy either for food or shelter.” During an assessment two weeks after the storm, bird sightings were down by 10 per cent from pre-storm levels.

PPSRNP’s neighboring key biodiversity areas, Cleoptra’s Needle Critical Habitat, Malampaya Sound Protected Landscape and Seascape and El Nido-Taytay Managed Resource Protected Area, were also hit by Rai, but assessments there are still ongoing, and the government and conservation groups have not yet provided figures on the true extent of the impacts of the storm on forests and wildlife.

Where did the wildlife go?

The state-run weather bureau reported that when Rai made landfall in Palawan, it had sustained winds of up to 150 kilometers per hour (93 miles per hour) and gusts of up to 205 kph (127 mph), battering the central and northern portions of the province. “With its vast coverage, how far could the birds, mammals and other wildlife have gone? So there’s a slim chance of escape,” Puna said.

Biodiversity expert Neil Aldrin Mallari said it’s possible some animals fled to more sheltered areas before the storm struck. “Wildlife have strong senses, most of them might have retreated,” he told Mongabay. “For those who were not able to retreat, because they’re not that mobile, like frogs, they might have perished.”

Mallari, chief scientist at the nonprofit Center for Conservation Innovation Ph Inc. (CCIPH), said he’s also concerned about the long-term survival of wildlife that did make it through the storm. “We hypothesise that, because of the strong typhoon, the flowers that would have been fruits by summertime, serving as food for wildlife, they might have been blown away; therefore, there would be famine in the wild, and eventually the wildlife might die out.”

Botanists are also concerned about the park’s plant life. “The hemiepiphytic and epiphytic species, like orchid, are the most affected as they cling on branches of the trees,” said Maverick Tamayo, research director of the nonprofit Philippine Taxonomic Initiative (PTI), which includes PPSRNP among its study sites.

Tamayo also noted that karstic or limestone-dwelling species are especially vulnerable to typhoons. “Those that have poor root system, for example, Amorphophallus species and tubers, can be carried away by the heavy rainfall since these species only thrive in humus within crevices of the limestones,” he told Mongabay.

On a positive note, he said, the passage of a typhoon can facilitate nutrient availability: “Typhoons can return and even out the nutrients in the forest through translocation … But still, typhoons, especially the strong ones, can have more negative impacts rather than benefits. For instance, opportunistic invasive species seeds and propagules can be effectively dispersed further.”

Prospects for a green recovery

Park superintendent Elizabeth Maclang said the destruction could have been even greater, and credited activities that have effectively protected the forest and managed the restoration of degraded areas. However, she said the park was not adequately prepared for a storm of this magnitude: “In the past, we’re spared [from] typhoons as strong as this, so we’d become complacent, and now we’re caught unprepared. Our big realisation from this? Invest in the improvement of our disaster readiness.”

The UN Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s sixth assessment report stated with “high confidence” that “the proportion of intense tropical cyclones (Category 4-5) and peak wind speeds of the most intense tropical cyclones are projected to increase at the global scale with increasing global warming.”

This further imperils developing countries like the Philippines, which on average sees at least 20 major tropical storms per year. Maclang is among the activists and climate negotiators in the Philippines calling on developed countries to set up a fund to compensate vulnerable countries for climate-linked losses and damages. “Our park hosts ‘globally significant habitat for biodiversity conservation,’” she said. “What we’d lose, the world would lose, so we urge developed countries to partake in raising this long-sought climate fund.”

Some efforts to increase climate resiliency are already in place. The park’s management has partnered with USAID’s Sustainable Interventions for Biodiversity, Oceans, and Landscapes (SIBOL) project, which launched in 2020. Some funds have already been channeled for post-Rai interventions in Palawan, including a “green assessment” set to begin in February, which will enlist the help of environmental authorities and nearby communities to pinpoint the changes in ecosystems since the typhoon struck.

The results of the assessment will be used to create hazard, vulnerability and community resources maps, aimed at guiding park management in crafting a plan to increase the park’s resilience to climate risks.

“We’ll help determine areas that will pave the way to green reconstruction, restoration and rehabilitation,” Mallari said. “In other words, it’s a pathway to a more resilient community.” With the assistance of community members as citizen scientists on a cash-for-work scheme, his team will also work to identify suitable habitat for various species, and their level of tolerance to disturbances before and after the typhoon.

Experts are looking towards green reconstruction, restoration and rehabilitation solutions. Image: Puerto Princesa Subterranean River National Park (PPSRNP).

Hitting the tipping point

Experts say the damage at PPSRNP is reversible, but note that it will take time to see full ecosystem recovery.

“If we leave it as it is and nature will take its course, it will definitely recover,” said Rogelio Andrada II, a forestry and protected area management professor at the University of the Philippines Los Baños.

Andrada said the inner forest, where post-Rai surveys have not yet taken place, may be in better condition than forest fringes, which received the most destructive wind force. In addition, standing trees without leaves are not necessarily dead and can sprout again, provided they don’t suffer from drought or attacks by insects, fungi or bacteria.

Without disturbances, the mix of tree species originally occupying the park can be expected to return naturally after about a decade. “Recovery starts the next day after a typhoon hit the area,” Andrada said. “But if you want it to return to climax vegetation, that would take a lot of time.”

The occurrence of equally strong or stronger typhoons in the future, as well as the incessant presence of people in opened canopies could disrupt this recovery process, he added. Moreover, park management is concerned about the risk of wildfires since no rains have occurred since Rai struck.

One technique that could speed recovery is “assisted natural regeneration,” which Andrada said entails replanting denuded areas with original species and ensuring these are protected from disturbances that could impact their growth and survival.

Mallari stressed the need to prevent further forest loss in Palawan, which he said is nearing the “tipping point,” beyond which ecosystems can no longer weather environmental pressures and perform their vital functions. As of 2015, the most recent year for which official figures are available, the province had just 694,459 hectares (1.7 million acres) of remaining forest cover, representing around 46 per cent of its land area. Losing 10 per cent more of this forest, Mallari said, is tantamount to hitting the tipping point.

“The challenge for us now is how we give it a hard reset, and if we’re able to, let’s make it count, because if we further let this degradation to continue, Palawan is moving towards that ‘point of no return,’” Mallari said. “If we hit that tipping point, any increase in population, for example, has an exponential effect on your loss of natural ecosystems. And the more ecosystems you lose, it increases your vulnerability when another Odette [Rai] comes. It becomes a vicious cycle.”

This story was published with permission from Mongabay.com.