A new study has identified the United States—the nation where the idea of mass production was born—as the world’s top producer of waste while also being the worst among industrialised nations at managing it.

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

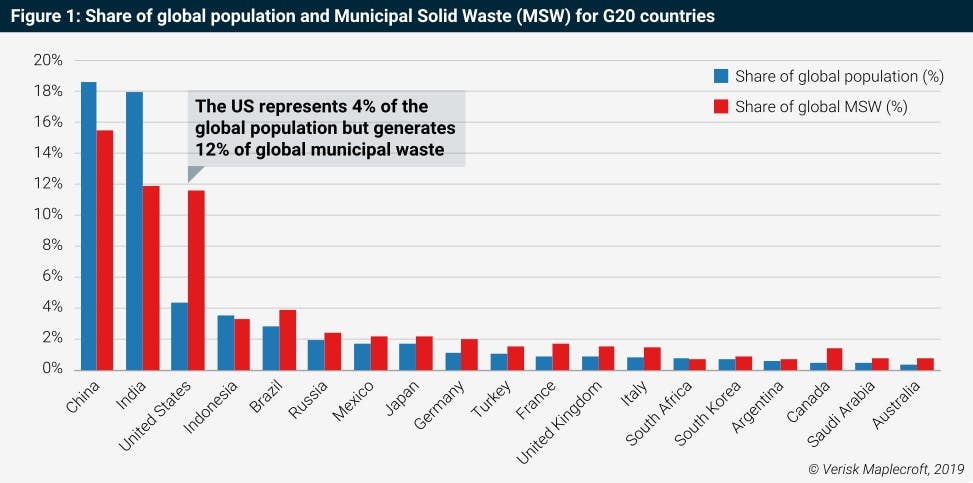

The US generates 12 per cent of global municipal waste—three times the global average—but only accounts for 4 per cent of the world’s population, reads the report, which was produced by Verisk Maplecroft, a United Kingdom-based research firm and consultancy specialising in global risk data and country risk analysis.

Worse still, of the staggering volumes of junk the country that created globalised consumer goods brand names such as Starbucks, McDonald’s and Coca-Cola as well as the Black Friday sales produces, only 35 per cent are adequately recycled, the study shows.

The research indicates that at 773kg per head, American citizens produce over three times as much waste as their Chinese counterparts, while municipal waste generation per capita is four times higher in the United States than in India.

But the US is not the only country that is bad at managing waste. While better than America at recycling, other industrialised countries, including the United Kingdom, Canada, Germany, the Netherlands and Australia, are also disproportionately responsible for waste generation, the study shows.

Share of global population and municipal solid waste forG20 countries. Source: Verisk Maplecroft

Asia, often made the scapegoat for the world’s plastic crisis, has undoubtedly contributed to marine plastic pollution, but such criticism has neglected the fact that Asian nations have traditionally served as the world’s trash dumps, with industrialised countries shipping their waste to the region for recycling to prevent their homelands from getting swamped by the goods they discard.

According to the report, plastic waste flows have been directed at developing nations that tend to lack the resources to recycle adequately. What’s worse, such deliveries have often contained a mixture of various waste types, which make adequate recycling difficult if not impossible.

But, the study shows, this era is coming to an end. As waste importing countries, including Thailand, Vietnam and Malaysia, are moving to limit the material they accept or ban it outright following China’s foreign waste ban 18 months ago, industrialised nations must find ways to reduce the rate at which they devour resources and deal with their own plastic waste rather than dumping it in the developing world.

Only recently, more than 100 containers of waste mislabelled as recyclable plastics Canada had shipped to the Philippines in 2013 and 2014 sparked a dispute between the two countries. It took threats of armed conflict from the Philippine government to pressure Canada to repatriate its waste in May this year.

Will Nichols, head of environment at Verisk Maplecroft, said given that awareness of the impacts of waste are at a peak, it was not surprising that countries in the region were moving to halt imports of waste.

“Although there are certainly concerns about the type of waste they are receiving from Europe and North America— often shipments are contaminated with difficult to recycle materials—these nations are realising they cannot continue to be the world’s dumping ground if they want to achieve their own environmental objectives,” he told Eco-Business.

How is Southeast Asia faring?

Waste trade aside, domestic recycling rates in Southeast Asia are nothing to boast about. Nichols said: “With the exception of Singapore and Taiwan, our recycling index shows waste is handled pretty poorly in Southeast Asia.”

“Every other nation in the region disposes of at least a third of its waste inadequately. Myanmar, Vietnam, Indonesia and Philippines all mishandle over 80 per cent of their waste,” he said.

“

There is a perfect storm forming where countries are already unable to handle the waste they currently produce, but will soon have even more to deal with.

Will Nichols, head of environment at Verisk Maplecroft

Verisk Maplecroft’s research identifies the Netherlands, the US and the United Kingdom as the countries where the introduction of new regulations on plastic waste could hit the companies that produce and use plastic in the pocket. But, Nichols observed, while many countries in Southeast Asia currently rank ‘low risk’, the amounts of waste these nations produce are on the rise as incomes increase.

“There is a perfect storm forming where countries are already unable to handle the waste they currently produce, but will soon have even more to deal with,” he said.

“Without major investment in infrastructure or rapid moves towards a more circular economy, we can expect a significant uptick in pollution, not just of rivers and soils, but increasingly the ocean too, where plastic particles present a severe threat to marine life,” he said.

A circular economy is a departure from existing modes production and consumption, implying that goods are repaired and recycled in order to minimise waste and ensure economic growth does not cost the earth.

Sumangali Krishnan, head of research and strategy for GA Circular, a Singapore-based consultancy devoted to finding business opportunities in post-consumer waste in Asia, told Eco-Business: “Southeast Asia is challenged given the limited capacity of existing waste management infrastructure.”

“Mismanaged waste – that is, uncollected or dumped waste due to limited waste management facilities – results in plastic pollution. Where collection exists, there is often limited source separation resulting in the limited or poor-quality collection of recyclables from household waste,” she said.

Southeast Asia’s recycling industry, she noted, is heavily reliant on an informal sector rather than the formal waste collection system. But, she adds, informal recycling systems could be vital in tackling the region’s mounting waste crisis.

Krishnan said: “The absence of complete diversion towards recycling combined with poor collection coverage has earned Southeast Asia the disrepute for plastic pollution. That said, the informal sector and recycling economy can definitely be harnessed to drive the collection of plastics for recycling and reduce pollution.”

The culpability of business

The seeming lack of resolve of developed nations to address waste issues domestically may turn into a mounting problem and result in a myriad of risks to businesses in the face of bans on plastic imports, Verisk Maplecroft’s study finds.

While the discrepancy between what is produced and what is recycled creates challenges for governments and populations, it is companies deemed to be the key drivers of waste production that may find themselves footing the bill if they fail to address the issue, the study reads.

“

As the waste crisis mounts, we will be spending a disproportionate amount of resources and efforts in responding to the various health and environmental disasters and challenges.

Sumangali Krishnan, head of research and strategy, GA Circular

As waste generation in countries soars, governments are more likely to establish more stringent regulations to reduce the levels of resource consumption, the study reads.

Such regulatory measures present additional costs to businesses in countries with insufficient recycling infrastructure. Often, the study points out, responsibility has been passed to the private sector, with companies having to finance disposal facilities and processes.

Already, companies face growing domestic pressure to deal with waste, notably plastic, as more than 60 countries around the world are introducing legislation aimed at mitigating the use of single-use plastics such as plastic bags, according to the research.

In addition, elevated rates of waste generation can lead to direct resource constraints. Plastic pollution, for instance, has already heavily impacted marine ecosystems and disrupted both fishing and tourism industries.

With global attention firmly fixed on plastic pollution, businesses linked to waste issues also face reputational risks for the impacts of waste on ecosystem services, biodiversity and human health, the study said.

Branded bottles washing up on pristine beaches, for instance, do not reflect well on a company at a time when consumers increasingly express a preference for companies that operate responsibly.

To avoid brand damage and financial risks in the wake of regulatory action, companies must develop action plans to shift production patterns towards circular material flows, the report reads.

“Companies, especially those connected with the production and manufacture of plastics for packaging, can lead the way in identifying interventions to bolster the recycling industry,” Krishnan noted.

The world generates over 2.1 billion tonnes of municipal solid waste each year – enough to fill 822,000 Olympic-size swimming pools, according to the report, but only 323 million tonnes (16 per cent) are recycled and a staggering 950 million tonnes (46 per cent) are disposed of unsustainably, the research has found.

The dramatic increase in rates of waste generation in recent decades is the result of rapid urbanisation, population and economic growth coupled with unsustainable consumer behaviour, according to the report.

“As the waste crisis mounts, we will be spending a disproportionate amount of resources responding to the various health and environmental disasters and challenges. This is especially wasteful when we have the opportunity to not only prevent such crises but, with the implementation of circular economy solutions, actually build on the economic potential of plastic waste,” said Krishnan.