What does it mean to live on the poverty line? For the poor in Brazil, one day’s income provides a bunch of bananas. In Japan, you could afford two carrots. And for people in Australia, you could get a full roast chicken, or a large bag of jelly beans.

While the poverty line is broadly understood as the minimum income humans need for the necessities of life, in reality many complex factors contribute to the decisions the poor make to feed themselves and their families.

Enter Chow and Lin – China-based economist and photography duo Stefen Chow and Huiyi Lin from Singapore. Using portraits of the food people living on the poverty line can afford to buy as the centrepiece, the artists explored the daily choices people face living on the bare minimum. Their project spanned 10 years, six continents and involved 200,000 kilometers of travel.

“

The breadth of decisions poor people have to make is a daily mental struggle.

Huiyi Lin

Image: Chow and Lin

Winner of multiple awards in Europe and exhibited in 15 countries and territories, the project was featured at the United Nations Conference Centre in Bangkok in 2018 for a session organised by the UN Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific (UN ESCAP).

The Poverty Line is now published as a book and available at the Nobel Peace Center in Oslo. It was recently featured in The New York Times as one of the top 5 visual books recommended.

In this interview, Lin Huiyi talks about the idea behind The Poverty Line, what poverty means to her, and how the Covid-19 pandemic has affected the lives of people living on the bare minimum.

How did you devise the concept for the project?

I’m trained in economics and Stefen is a photographer. We moved from Singapore to China in 2008. It was a very exciting time of exploration, understanding China and its relationship with the world.

We became particularly interested in how poverty and inequality varies in different countries. I had previously worked in the Ministry of Trade and industry in Singapore. From a public policy perspective, these issues are national policy issues and don’t often get communicated to people on the ground.

Photography became the visual medium we used to connect people with these issues. We did a lot of research on the economic frameworks, understanding how poverty is understood and defined in different countries. That was when we realised we hit upon something important, and that formed the basis of our work.

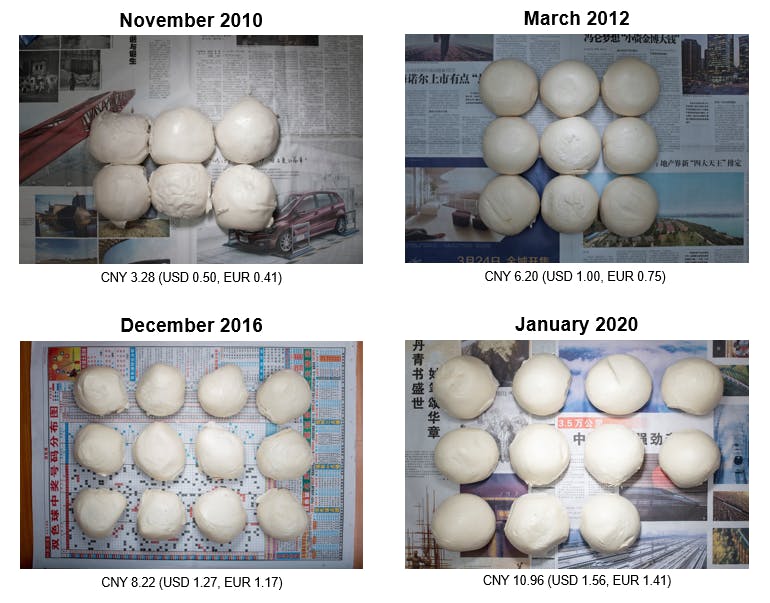

Case Study – China

These photographs show how the number of mantou (steamed plain buns) that a person living in poverty in China can afford has changed over the past decade (2010 - 2020). Factors such as poverty line adjustments and inflation affect the affordability of a staple food in China. Image: Chow and Lin

How did people react to the work?

The photographs triggered people to think and debate, and even challenge us. Food is something anyone can easily relate to, but the situational context of our own environments and our own assumptions of other countries and other cultures come into play.

There were people from Russia who remarked, “the vegetables in China look so fresh and green… unlike the vegetables we find in Russia.” But when netizens from China looked at the photos, they were outraged. They could not believe people could survive on so little.

That was what really got us thinking: How do we then make this bigger than what we set out to do?

So we started applying the same visual concept to different countries. As soon as we had the opportunity to visit a new geography, or if we saw interesting trends unfolding, we seized it. But the project has grown organically.

A person living on the poverty line in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil would be able to afford a bunch of bananas with a daily income of BRL 2.33 (USD 1.23) in 2012. Image: Chow and Lin

What was the thinking behind the foods chosen in your photographs?

There are three principles to it. The first is to choose foods that are available at supermarkets and markets where locals go. Second, we picked foods that are economic staples; they’re made up of carbohydrates, proteins, fruits and vegetables. Third, to examine the decisions people make every day.

Some people have asked why we included snacks [Chow and Lin’s work includes a photograph of deep-fried chicken feet]. Or why we even feature ‘expensive’ proteins like fish, something not often seen as a food choice for the poor.

We were inspired by a book called Poor Economics, written by Nobel laureates in economics, Professor Esther Duflo and Professor Abhijit Banerjee. One of the key lessons from the book was that people living in poverty are in very similar situations, and can be as rational or irrational as any other person. We shouldn’t assume that they should only want the very basic necessities. If they earn a little bit more income on a particular day, or if it’s a good day of harvest, they might choose something better like fish, or sweets for their children. It’s aspirational. They make these choices with very limited resources. The breadth of decisions they have to make is a daily mental struggle.

A person living on the poverty line in Paris, France would be able to afford 8 red endives with a daily food budget of EUR 5.99 (US$6.73) in 2015. Image: Chow and Lin

Why do you use newspaper as the backdrop in your photographs?

A lot of artwork or photography that focuses on poverty uses clichéd imagery, which can numb audiences to feel moved in that moment, but they may not take anything away long after the experience.

We wanted to create something that evokes a sense of empathy in our audience. That’s why we chose common objects that anyone can relate to. Everybody understands whether or not eating an egg or a slice of bread is going to sate their appetite.

The use of newspapers was something we experimented with that just seemed to work. Newspapers are commonplace objects that people can usually afford, and give the image a sense of place and time.

A person living on the poverty line in Cape Town, South Africa would be able to afford two cans of sardines (pilchards) with a daily income of ZAR 27 (US$1.81, EUR 1.75) in 2019. Image: Chow and Lin

Were there instances over the decade you’ve worked on this project that surprised you?

I’ll give a few examples. When we were in Rio de Janeiro in Brazil in 2012, the economy at that time was growing very quickly, with a lot of infrastructure being built. We found that a day’s worth of income for a person living on the poverty line was equal to the cost of a bus ticket to get to the other side of town.

This was significant because the locals buy food from the local stores in the favelas, or the slum areas. The food prices were expensive because they are sold in small quantities and didn’t have economies of scale. The prices could also be influenced by local gangs.

Cheaper options were available in the hypermarkets in the surrounding parts of the city, but you need transport to get there. The cost of going to the hypermarket was basically worth a day’s income if you are living on the poverty line.

In the US, nutrition is a challenge for low-income consumers. We realised that fresh produce actually comes at a premium. If you’re living on a very small budget, the choices are fairly limited to eating processed foods such as frozen TV dinners, which are widely available. That’s the result of the way the food supply chain is structured, and how fast food culture is shaped.

In many other countries, inflation was a common trend, even for food. But we found that in Vietnam food prices had been decreasing. This was the result of cheaper imports of vegetables and fruit from China. Of course, that has implications for local farmers in Vietnam competing against lower priced products, but from the perspective of poor Vietnamese consumers, lower food prices was a good thing.

A person living on the poverty line in New York, US would be able to afford three cheese burgers with a daily food budget of US$5.46 (EUR 4.84) in 2019. Image: Chow and Lin

How does an economist value art?

Art is a way to engage people on complex issues for which there are no straightforward solutions, such as climate change and poverty.

A lot of problems are intertwined because of the social structures or economic systems in place, and art also allows people to collaborate and recognise that we all need to be part of the solution if we are all part of the same problem. That’s the motivation behind our art and the way I’d like it to move forward.

Do you feel The Poverty Line paints a reliable picture of the poverty people are living in at the moment? What do you understand poverty to mean?

There are two ways to define poverty. One is absolute poverty – a fixed amount of income needed for an adult to survive and meet their basic needs for food, water and shelter in a given country. It’s the survivability threshold.

The other is relative poverty, which defined as the income gap between the average person in the population and lower income groups. Many European countries adopt the relative poverty measure (about 50 – 60 per cent of the median income of the population) as the poverty threshold.

We’ve learnt that governments find it necessary to measure and monitor poverty, but the issue is multi-dimensional. Besides just income, poverty means lacking access to resources, such as education, healthcare, job opportunities and transport.

The United Nations or the World Bank, for example, focus on poverty more from a survivability or a “bare minimum” perspective that applies to the more international sense of what ethical human development is. But countries have their own definitions of how different parts of society need to be taken care of. So local context is important for defining what poverty means in different countries.

How is poverty changing in modern times?

A key learning point we took away from this project was how tightly inter-connected social issues are. Ten years ago, the world was a relatively stable place. Major economies had certain political regimes in place, and things seemed to be moving along in a pretty optimistic way. But trom 2015, we started seeing breakouts of political instability, across the Middle East, the protests on Wall Street, and the yellow vest movement [which started in France in 2018, with protesters agitating against high fuel prices and the rising cost of living, and spread to 32 other countries].

Our project gave us insight into what didn’t seem right at the time. Poverty rears its head in ways that show how people live; it illuminates whether or not people’s material needs are being met, and if opportunities for prosperity are accessible to everybody.

Post-pandemic, is it worth being optimistic about a sustainable economic recovery?

For lower income groups relying heavily on the informal sector, Covid has exacerbated the problems they face — job security, access to infrastructure, and healthcare are all harder now.

The global food supply chain is so inter-connected – from production to trading to consumption and food culture. We see the same variety of bananas all around the world; Oreo is the most popular biscuit in the world found everywhere you go.

Disruptions such as Covid affect food supply on the ground on a daily basis. From logistics at production sites, to the availability and affordability of food at the supermarket, and the price at which it lands on the dinner table.

These issues are never too complex to try and understand and do something about, but they are never too simple either. Poverty impacts all of us. What matters most is: how do we contribute meaningfully to the conversation around poverty and take the action needed to reduce it?

This interview has been edited for clarity and condensed.

The Poverty Line is available in French and English, and is on sale in Singapore.