A nationwide ban on single-use plastics in the Philippines will hinder the country’s transition towards a circular economy, industry experts said.

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

They are instead pushing for an extended producer’s responsibility (EPR) scheme, where private companies using plastic will be responsible for paying the cost of its collection, sorting, recycling and safe disposal.

The single-use plastics regulation bill, which consolidated 38 existing bills seeking to phase-out or regulate plastic bags, sachets, utensils, was approved by congress in March. It is now being reviewed by legislators for plenary debates. It will still have to get approval by the senate before it can be signed into law by the Philippine president Rodrigo Duterte.

“Single-use plastics cover most packaging materials. If you remove it and replace it with compostable material, the circular model is useless,” Bonar Laureto, executive director of non-profit Business for Sustainable Development (BSD), told Eco-Business.

“A shift to compostable alternatives, which are designed to degrade after single-use goes against the reusable model of the circular economy.”

“

Single-use plastics covers most packaging materials. If you remove it and replace it with compostable material, the circular model is useless.

Bonar Laureto, executive director, Business for Sustainable Development

BSD creates the sustainability reports and impact assessment for 53 of its members including Nestlé, Unilever, Coca-Cola, and Monde Nissin—food and beverage giants which beach audit studies have shown to be among the world’s biggest marine plastic polluters.

Laureto, who is leading an ongoing BSD research that studies options to the proposed plastic ban, is instead calling for the amendment of the existing Republic Act 9003 or Ecological Solid Waste Management Act of 2000, to include provisions on the practice of EPR in the Philippines.

Several bills have already been filed over the past four years mandating EPR, but legislation on it has been dragging.

Collected plastic materials are upcycled into marketable products like long-use plastics like pails, benches, slides or as an additive to asphalt road construction replacing bitumen, said Laureto.

A multi-sectoral organisation advocating for zero waste, whose members are similar to BSD’s, is supporting the same approach.

“Industry is in favour of an implementable EPR system that is inclusive, measurable and holds stakeholders accountable for the recovery of their plastic and packaging with reasonable and attainable targets,” Crispian Lao, founding president of the Philippine Alliance for Recycling and Materials Sustainability (PARMS), told Eco-Business.

Lao called for an EPR system that integrates and improves the livelihood of waste-pickers by putting more recyclables and set up the infrastructure for the recovery of low value recyclables.

Recycling in the country is focused on high-value plastics like polyethylene terephthalate (PET) and high-density polyethylene (HDPE) that is readily available in junk shops, but because of limited infrastructure for recycling of low-value plastics like single-use sachets, they usually end up in landfill and contribute significantly to the pollution of oceans.

Lao, also the managing director of a local plastics company, added that a plastic ban would cause a shift to compostable alternatives like glass, steel or paper which will only add to greenhouse gas emissions during the transport phase.

“Bans on plastic products and packaging without environmentally sound and economically viable alternatives will result to a bigger volume of mismanaged waste in a different form due to lack of government infrastructure, and increased cost to the consumers which can be inflationary,” said Lao.

However, anti-plastic advocates said initiatives pushed by industry groups and corporations like chemical recycling, plastics-to-roads, ecobricking, plastic credits, and plastic collection in exchange of basic goods for low-income families is “greenwashing”.

“Their methods require ongoing extraction of resources, because they fail to keep valuable materials within a circular economy, and generate harmful emissions of heavy metals, persistent organic pollutants, and greenhouse gases,” argued advocates from Break Free From Plastic and Heinrich Böll Foundation in an opinion piece.

Are zero waste cities a viable solution?

Even without an outright plastic ban, the city of San Fernando, Pampanga in the Luzon island group has been a “zero waste model city”, where most of its trash has been diverted from landfill.

Every household in its 35 barangays (village or community) segregates its own waste, has segregated collection, and each barangay has an operational materials recovery facility (MRF), where biodegradable waste is converted into fertiliser, recyclable material is recycled or sold to junk shops, and residual waste is collected for transport to sanitary landfills.

The city partnered with non-government organisation Mother Earth Foundation in 2012 to start its zero waste programme, which follows a door-to-door biodegradable and recyclable collection that ensures compliance of every household in the city.

The metropolis, with a population of over 300,000, established more than a hundred MRF’s, exceeding the requirement of the law of only one facility for every barangay.

Sonia Mendoza, chairwoman of Mother Earth, said that in 2012, 12 per cent of its total waste was diverted from the Clark Sanitary Landfill, costing the city some US$1.5 million per year in waste disposal.

After six months of implementing the zero waste project, the waste diversion rate increased to 53 per cent. Today, the waste diversion rate is 80 per cent, the highest in the country. San Fernando’s cost of disposal to the landfill is down to about US$250,000, climbing to US$300,000 in 2018 due to tipping fee increases.

Some cities in Metro Manila like Fort Bonifacio in Taguig City, Potrero, Dampalit, San Agustin, Concepcion, Hulong Dagat in Malabon City, among others, have likewise demonstrated successful source-separation programmes that prevent organic waste and recyclables from being dumped in landfills.

Lao, a former commissioner of the National Solid Waste Commission (NSWC), noted how other cities could attain an 80 per cent diversion rate like San Fernando, but face restrictions.

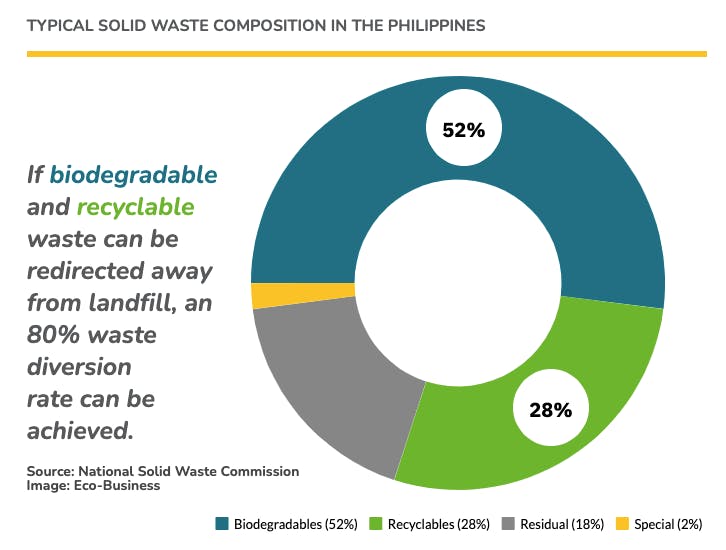

According to the NSWC, a typical solid waste composition in the country is 52 per cent biodegradable waste and 28 per cent recyclables. Lao said diversion of these wastes could be achieved if the Ecological Solid Waste Management Act of 2000 was strictly followed, where local government units are primarily responsible for drafting policies, collecting, recycling, and composting of waste, as well as maintaining MRF’s and sanitary landfills.

These facilities are constructed out of local funds, grants, and loans but have attained a limited degree of success with only 10,730 MRFs in the country as of 2018, catering to a meager 33.3 per cent, or 14,000 out of the total 42,046 barangays, based on NSWC data.

“[Zero waste cities] cannot be easily replicated because other high density urban areas do not have the space to do composting activities,” he said.

“Some cities don’t even have barangay halls (seat of local government in the barangay). And oftentimes politics come into the picture as the funds need to be downloaded if it is not a city programme,” he said. “In rural areas the challenge is more on funding resources.”

“

Corporations and industries insist on using single-use plastic despite knowing the harms that these products cause, because they don’t want to bear the expense of changing packaging or adopting reuse systems.

Marian Ledesma, zero waste campaigner, Greenpeace Southeast Asia

A national plastic ban is necessary

Zero waste cities may have been able to curb plastic trash, but still struggle with managing the sheer volume of it, said Miko Aliño, Asia Pacific programme manager for Global Alliance for Incinerator Alternatives (GAIA).

Local governments in tourist draws Boracay in Malay, Aklan, Siquijor, and Batanes have likewise made initiatives to regulate plastic use in their respective jurisdictions, but Aliño said “it is absolutely necessary for the national government to enact a more comprehensive national regulation banning single-use plastic to make these local laws more effective.”

He added: “Until problematic packaging have been removed from the market, the Philippines will continue to struggle with plastic waste.”

After China and Indonesia, the Philippines ranks as the world’s third biggest polluter, with 2.7 million metric tonnes of plastic waste generated each year.

Greenpeace Southeast Asia zero waste campaigner Marian Ledesma said that the plastic pollution crisis is not just a matter of waste management, but “a systemic problem with harmful impacts throughout the life cycle of plastic.”

“Corporations and industries insist on using single-use plastic despite knowing the harms that these products cause, because they don’t want to bear the expense of changing packaging or adopting reuse systems,” Ledesma told Eco-Business.

“But by refusing to shift away from plastic and changing current processes, corporate polluters are externalising the costs so people are bearing the burden. Communities, especially the vulnerable and marginalised, end up paying for the impacts and costs on continued use of single-use plastics.”