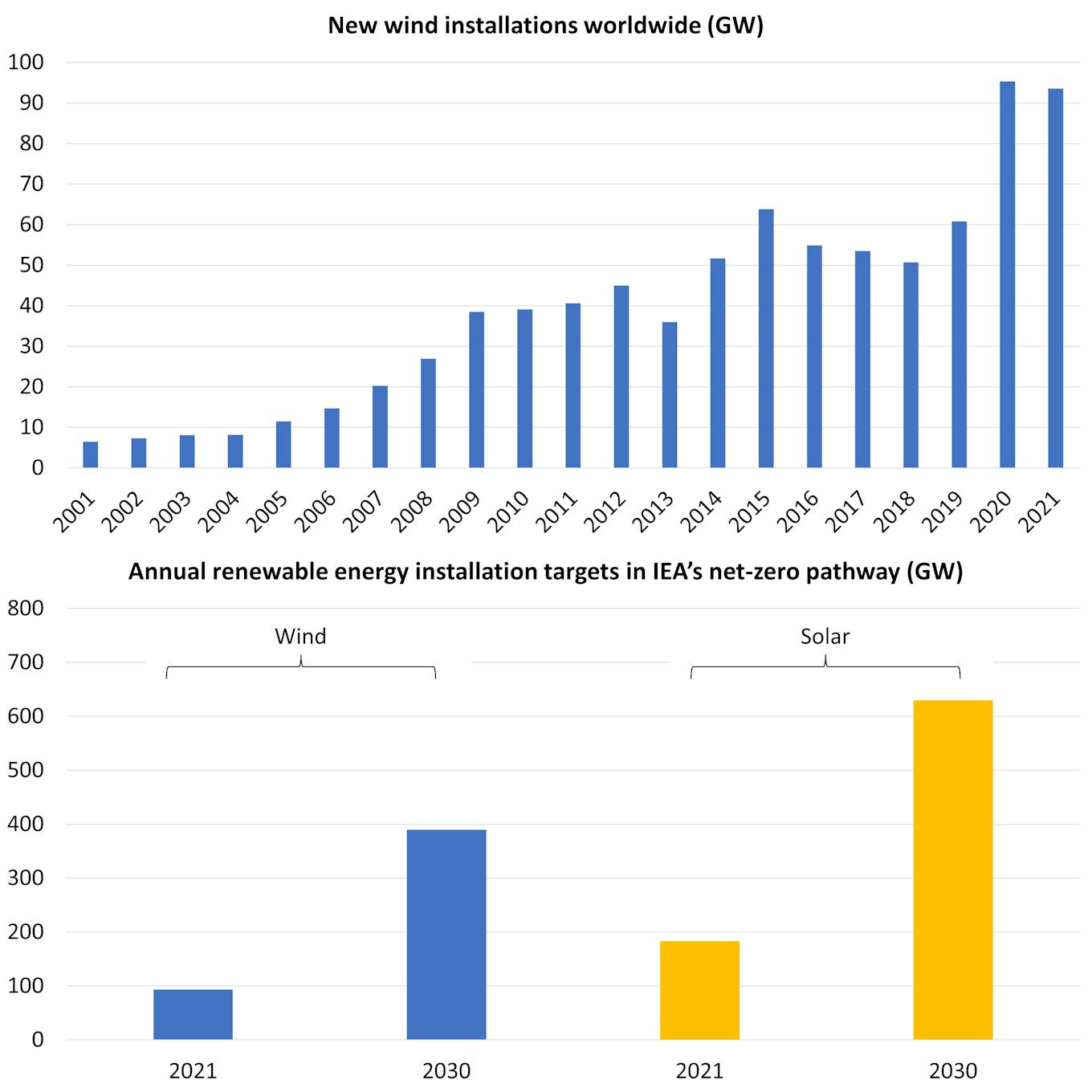

In 2020, while Covid-19 brought the world to a standstill, the wind power industry reported a windfall – a record 95.3 gigawatts worth of new projects were built. That was a 57 per cent increase compared to 2019.

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

Last year, new installations fell to 93.6 gigawatts, according to figures from the Global Wind Energy Council (GWEC), a Belgium-based international trade association.

The drop was largely due to financial incentives ending in China and the United States. Mild boom-bust cycles have also plagued the market in the past decade.

But such hiccups are becoming increasingly costly for a world relying on the proliferation of clean sources of power to quickly address climate change and energy insecurity.

Wind energy, along with solar, are among the most effective solutions by cost and carbon-saving potential, said scientists in the latest report by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Global carbon emissions need to drop nearly 50 percent by 2030 and reach net-zero by 2050 to limit global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius and keep humanity safe from the worst climate risks.

To hit such heady targets, annual wind power installation needs to hit 390 gigawatts by 2030, or four times the current rate, according to the International Energy Agency. For solar power, 630 gigawatts needs to be generated by 2030, up from about 183 gigawatts last year, predicts analytics firm BloombergNEF.

Top: New wind installations worldwide. Bottom: Wind and solar installation targets for 2030 in the International Energy Agency’s net-zero pathway. Data: GWEC industry report 2021, 2022, IEA, BloombergNEF.

Scaling so quickly is likely to be tough for the wind sector, with the upfront development costs of giant turbines being several times higher than that of solar panels, especially if they are built out at sea to catch stronger winds. Unlike wind, the pace of yearly solar installations has never dipped in the past decade, according to BloombergNEF data.

“It will take a lot of focus,” said Dave Jones, global programme lead at climate and energy think tank Ember.

“You need governments to be really paying attention to all the issues, to make sure there are no bottlenecks to unlocking ambition,” he added.

While short-term price and shipping issues exist, energy experts said that ramping up wind power installations is contingent on good governance – such as by providing simple regulations and ambitious roadmaps. Regulatory wrangling could throttle the growth of the world’s cheapest forms of electricity, they add.

Permitting woes

Bureaucratic bottlenecks is an ongoing gripe for the wind developers that have secured contracts but need a government’s green light to proceed.

Permitting can stretch up to eight years in Europe and Japan, according to GWEC. In the United Kingdom, only 16 land-based wind turbines were permitted between 2016 and 2020.

The backlog has a toll. The number of new projects in the UK fell over 90 per cent in the past seven years. A reduction in financial incentives also put a brake on growth. Europe’s wind lobby said slow approval is a key reason why interest in wind projects has fallen in Italy – only 30 per cent of its latest round of wind auctions were awarded.

“Permitting is a universal barrier for wind energy,” said Joyce Lee, GWEC’s head of policy and projects, at a webinar this month. GWEC said that governments should enforce a cap on permitting time and beef up resources available to look into wind permits.

There have been calls worldwide for a “one-stop shop”, or a central government office, to facilitate faster paperwork. As it stands, the process could involve multiple departments, from finance to environment to defence.

Things didn’t always take so long. In the UK, permitting slowed considerably after residents complained that the turbines were ugly and noisy. There are also fears badly sited projects could pose a risk to birds.

“In the interest of minimising the environmental impact of wind farms, a certain timeframe to do permitting is really important,” said Oliver Metcalfe, head of wind research at BloombergNEF.

“We go into a project and community with 20 to 30 years in mind. When a government makes decisions, they make it in the 30 to 50 years’ time frame. I can appreciate why they take longer, why they have to be measured in their approach,” said Nitin Apte, chief executive of Vena Energy, which has solar and wind energy projects across the Asia Pacific region.

But there remains room for improvement, Apte added.

“The wind industry is looking for clarity and efficiency,” he said. Clarity in terms of which government departments are involved, and efficiency — by designating wind and environmental impact studies to governments to complete ahead of auctions.

Such help with the permitting process is especially important because wind energy projects have to overcome more hurdles than solar before becoming operational, according to Apte. For example, turbines need to be typhoon certified in Japan and the Philippines. Apte said Vena Energy’s solar projects could be permitted in just over a year or two, several times faster than the wind projects.

Protracted permitting times also provide a bigger window for external shocks, extending projects timelines. The supply and logistics price spikes from the post-pandemic industrial recovery and the Russia-Ukraine crisis are affecting projects auctioned some three years back, said Apte.

“There’s not a lot you can do about that,” he said.

However, the Ukraine crisis could see the acceleration of clean energy projects given the increasing focus on reducing reliance on Russia’s gas supply. The European Union has set a year-end deadline to cut two-thirds of its gas imports from Russia. Last month, Italy cleared the construction of six wind farms, in a bid to reduce its reliance on Russian energy imports. This month, the UK has vowed to cut permitting times for offshore projects from four to one year. It has also said it will phase out imports of Russian oil by the year end.

Clearer, more ambitious outlook needed

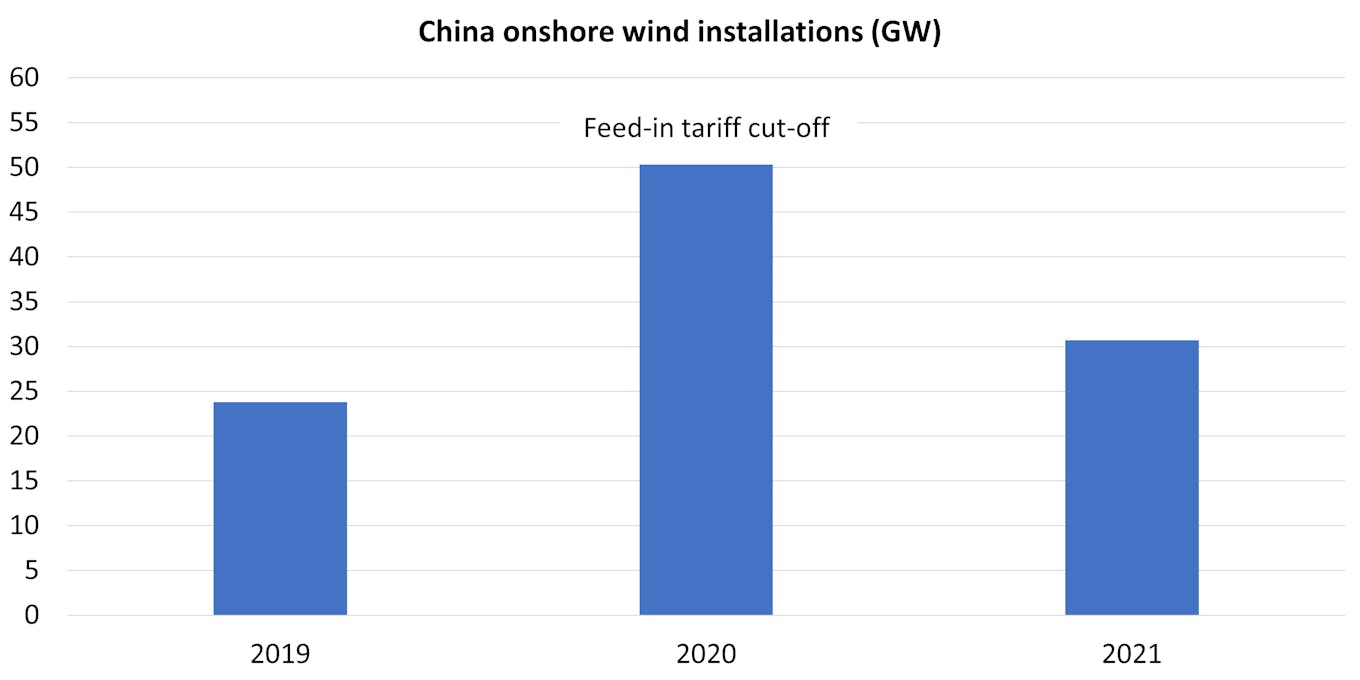

China, the world’s biggest wind market, told developers to complete their onshore projects by the end of 2020 to be eligible for central government subsidies and favourable prices. Installations more than doubled that year compared to 2019. The surge meant that east Asia accounted for about three-fifths of global installations, up from about 50 per in 2019.

But the number of installed projects tumbled by almost 40 per cent in 2021, as developers now have to bid in competitive auctions to secure projects, lowering the price at which they can sell electricity.

It’s no surprise numbers fall after financial support expires, said Metcalfe at BloombergNEF. But the key to recovering from that is to provide visibility on what comes next.

“Uncertainty isn’t good in terms of maintaining installation rates,” he said.

Policy visibility could determine how fast the industry grows in the next few years. Similar subsidy measures in Vietnam are set to expire 2023, and there are scant details about how the auction system will look like once those incentives are removed.

“Wind requires huge levels of investment and this requires clear and stable regulatory frameworks. Any unexpected changes causes uncertainty and will result in a reduction in the appetite to deploy new renewable capacity,” said Xabier Viteri Solaun, managing director of Spanish energy firm Iberdrola Renewables, which specialises in wind power.

Analysts added that future government plans will also need to be more ambitious, so that the number of project openings can match the market interest.

“Auctions used to be just the remit of large European utilities. Now we’re seeing more pure-play project developers as well as oil and gas companies with deep pockets getting involved, especially in offshore wind,” said Metcalfe.

“The supply of projects hasn’t kept up with demand, so that means competition is really high and that is driving down the costs that we’re seeing in auctions,” he added.

GWEC warned in this year’s industry report that the plunging price of wind energy could deflate market enthusiasm.

Some positive signals are coming out of Europe. The UK is shifting from biennial to annual renewable energy auctions to speed up adoption. Germany is setting aside 2 per cent of its land for wind farms. Both countries increased their wind energy targets this month.

Part of the solution could also be adding qualitative criteria in the design of wind project auctions. This could ensure that firms have the incentives to provide more jobs for locals or create less pollution, instead of pinning business plans purely on price.

Such mechanisms are already used in Japan, where factors such as cooperating with fisheries on offshore projects and boosting the local economy are prized. Germany is considering adding criteria in sustainability and innovation.

Other markets, such as the UK, still focus largely on cost, according to Metcalfe.

Crucially, governments will have to fortify their electricity grids to support variable output from wind farms, and accelerate the phase out of fossil fuels to create more market space for renewables, GWEC added.

The trade group said competition with gas power, which is more expensive but less variable, is a key issue for the industry in the next five years. Both the gas and wind industry are eyeing emerging markets in Southeast Asia, where electricity demand is set to increase 60 per cent by 2040.

Headwinds forecasted

High shipping costs associated with the pandemic are likely to come down. However, steel prices have skyrocketed predominantly due to the Russia-Ukraine conflict, piling pressure on manufacturers whose turbines are three-quarters steel.

“It is important to realise that when input costs rise, the cost of wind is going to rise. That is something that has not necessarily needed to be communicated until now,” said Metcalfe

The scramble for critical minerals that are used in wind turbines, electric vehicles, solar cells and semiconductors, will also drive prices up particularly as mining is concentrated in only a handful of regions in the world. China is a big supplier but Beijing made it clear in its latest five-year plan that exports would be cut to satisfy growing domestic demand.

But GWEC said the outlook for the wind industry remains positive, buoyed by national decarbonisation and energy security agendas. It expects 557 gigawatts of new wind installations by 2026, regardless of the hurdles.

Apte said that wind projects do have their inherent benefits over solar power in the renewables space, such as being more efficient in generating electricity.

“Wind does take a bit longer than solar to develop but the benefits are also commensurate,” he added.