So, exactly 12 minutes before boarding a plane to Jakarta on Saturday, I get a call.

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

It’s the head of international media relations from Asia Pulp & Paper, Randy Salim. It’s about the press trip that I’m just about to go on to check out their new mill in South Sumatra, which will be one of the world’s largest.

There’s a problem. APP are sorry but the trip’s been cancelled.

Um, why? I’m literally about to board the plane.

Well, the focus of the trip will now be on the commercial and financial aspect of the new mill, and not the sustainability angle. So there’s no story for you at the moment, I was told.

“You wouldn’t get the full experience for a sustainability story”, they explained, adding that the trip would be rescheduled for a more suitable trip for the sustainability press at a later date.

Curiously, the night before, APP’s comms guy had called to ask what I wanted to get out of the trip.

I told him that besides an understanding of how the mill works, and what it is capable of, I’d want to know how such a big mill can avoid breaking the zero-deforestation pledge that APP has made.

Four years ago, following a long campaign by green groups, APP, Indonesia’s largest pulp and paper company, promised to stop cutting down rainforest to feed its pulp mills.

APP has a history of breaking promises, and critics say the new mill will inevitably mean more deforestation in Sumatra to feed the mill’s enormous appetite for timber.

Its acacia plantations simply do not have enough trees to feed the mill and Asia’s increasing appetite for paper products such as toilet roll and tissues.

Even so, Salim said that the company would have an answer for my zero-deforestation question, although there was a snag with the arrangements for the trip.

Heavy rain and flooding had made access to a village near the mill impossible, they said. APP had wanted to showcase the village as an example of how a community engagement project was working to change the culture of forest burning to clear land.

To get around this, I was told, villagers would be brought to the mill where they would be available for interview anyway, so that part of the story could still be told.

But, just before getting on the plane to Jakarta, it became apparent that the compromise would not be a good enough “experience” for sustainability journalists. So the trip was off.

Could I just go along anyway? My editor later asked Salim.

Nope. I would not be hosted even if I showed up in Jakarta.

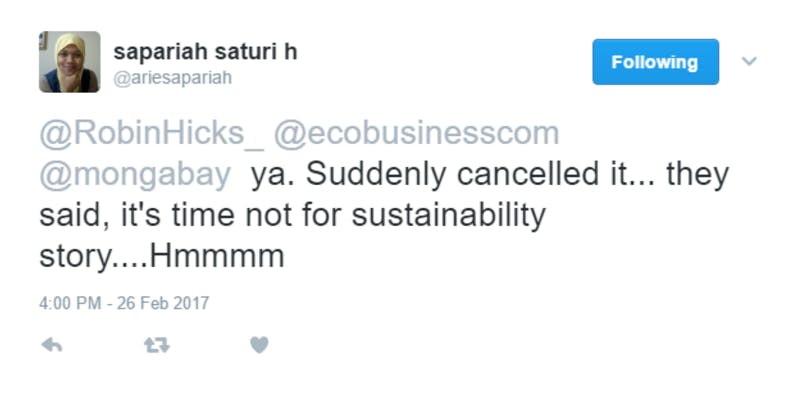

Before I could take this too personally, it emerged that the Indonesia editor of environmental journalism website Mongabay, Sapariah Saturi, was also suddenly uninvited.

She tweeted this, in response to a tweet I’d posted earlier:

But curiously, Audrey Tan, environment and science correspondent for Singapore’s The Straits Times, and Wataru Suzuki, Indonesia correspondent for the Japanese business title Nikkei Asian Review were not uninvited.

Apparently, this was because their stories would focus on the “business and finance” aspects of the mill, not sustainability.

But here’s the thing. Every story that has been written about the mill at Ogan Komering Ilir (OKI) has covered the environmental implications to some degree.

It’s virtually impossible for a journalist to write a story about a mill capable of churning through 70,000 hectares of timber a year without touching the sustainability angle.

Even The Jakarta Post failed to avoid it in a puff piece that hailed the launch of the mill in March last year. Right at the end of the story, it is mentioned that Indonesia’s pulp and paper sector is under scrutiny from international green groups.

Maybe it’s the sort of reporting that APP is worried about.

Eco-Business ran this piece at the start of the year, headlined ‘NGOs decry APP’s new giant paper mill’. The story cited criticism from green groups, and noted that the company had very quietly let it be known that production at the mill had begun, via a small pulp and paper trade publication just before Christmas.

Mongabay has taken a similar line, pointing out that limits on wood supply for the likes of APP have raised deforestation fears. APP would not have enjoyed the first line of the story, which pointed out that the company has “spent decades eating through Indonesia’s vast rainforests.”

But The Straits Times has been skeptical too. The paper, which tends to be pro-business, published this story in 2015, which highlighted how the mill could well mean more peatland destruction, more deforestation and more suffocating haze for Indonesia and its neighbours. And it published a story voicing the concerns of green groups just last month.

So does APP think the ST will now suddenly stop asking tricky questions about the environmental implications of the new mill?

Audrey Tan has written about APP before, highlighting how the company was among the first to be blamed for the record haze crisis in the region in 2015. The top story listed on Google written by her is about APP products being stripped from the shelves of Singapore supermarkets after it emerged that fires were started on the company’s concessions. Her story pointed out that other firms were ‘escaping the shame and blame’ for the haze.

In the bitterly competitive agroforestry sector, it is a story that APP will have liked very much. It took some heat off them in one of the most uncomfortable periods in the company’s history.

So what about Nikkei writer Wataru Suzuki? Well, he hasn’t written about Asia Pulp & Paper much yet. But he has covered plenty of stories about its parent firm Sinar Mas, such as when the conglomerate acquired a stake in a struggling coal investment firm, and when it started a massive telecommunications project to connect Indonesia’s eastern provinces.

Whatever the real reason for the black ball, it will be interesting to see what coverage emerges out of a media trip in which some members of the press were intentionally left out after being invited.