Communities around the world are already feeling the impacts of climate change. Finance is at the heart of the matter: adapting to rising sea levels, heat waves, floods and erratic weather is becoming expensive very quickly, particularly for developing countries.

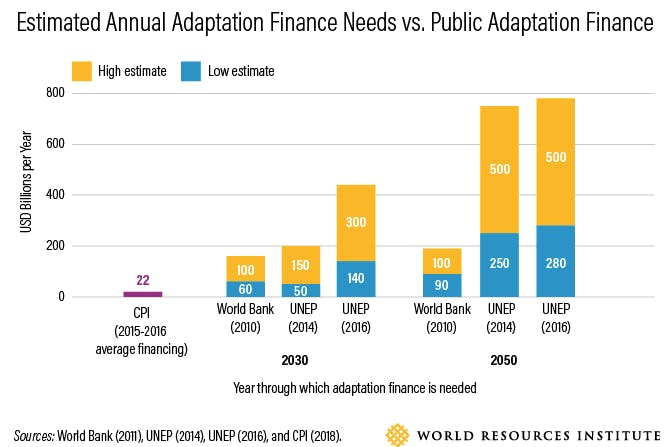

Estimates of annual costs of adapting range from $140-300 billion per year in 2030 to nearly double, $280-$500 billion per year, in 2050. Yet in 2015-2016, international public climate finance for adaptation averaged only $14.79 billion per year. These flows support critical investments like climate-smart agriculture and more resilient infrastructure, but they pale in comparison to the projected costs of preparing for and responding to climate impacts.

Countries on the frontlines of climate change are already using their own scarce domestic resources for adaptation to supplement international flows. The key for them is to use limited international and public finance as effectively as possible. That’s where civil society organisations (CSOs) can come in, and why WRI’s Adaptation Finance Accountability Initiative (AFAI) is working with CSOs to help them do just that.

Communities are at the center of climate finance

Many national governments can and are establishing climate expenditure tracking and monitoring systems to ensure that scarce flows of climate finance address priorities. This is one essential step toward determining whether finance is being used effectively and helping the communities who need it the most.

CSOs are also increasingly including climate issues and finance in their action agendas. In some cases, these groups are tracking and monitoring local and national budgets and financial flows themselves, to ensure that funds are reaching the right projects and communities. They are also evaluating the effectiveness of climate adaptation projects and advocating for change on a range of related issues — from water management to education to infrastructure, helping ensure that governments are listening to citizens’ needs. AFAI and our local partners are supporting their efforts by training CSOs in Ethiopia and Uganda to analyse available government budgets and preferences for climate-related investments, work with communities to prioritise their needs, inform decision-makers, and shape government investment decisions and the overall use of funds.

We’re basing our work on past experiences. For example, in the Philippines, the Institute for Climate and Sustainable Cities (iCSC), an early AFAI partner, found much more funding for adaptation was flowing into the country than was being reported by the government. From 2010-2013, the Philippine government and its international partners committed $880 million for adaptation, but only disbursed $396 million, and only a fraction made it to local communities. In response, the Philippine parliament created an Oversight Committee on Climate Change in 2014, strengthening management of adaptation finance in the country.

And in Uganda, the national government doesn’t yet have a system in place to track or code adaptation finance within the national budget (though it’s under development). Climate and budget advisory CSOs like the Civil Society Budget Advocacy Group and Climate Action Network Uganda are learning to track whether national and international resources for adapting to climate change are channeled through accountable mechanisms and if they reach vulnerable communities. Working with AFAI, these groups mapped the national finance landscape and tested methods to track adaptation finance.

But this is just the beginning. Much more needs to be done by governments, including: engaging and empowering a wide range of community stakeholders in determining local adaptation priorities and implementing adaptation actions; improving local and national decision-makers’ capacities to design and implement appropriate adaptation solutions; and evaluating the effectiveness of resilience investments. What’s working—and what’s not—should inform future plans across sectors to make sure money is actually building local communities’ resilience and reflecting their priorities.

Maximising the impact of scarce adaptation resources

Tracking and monitoring national climate-related spending is a necessary first step to maximise the impact of scarce adaptation resources. Effective systems will enable countries to ensure funding flows down to local levels and to continuously measure progress.

With strong tracking and monitoring systems, governments, civil society and communities will be better equipped to understand which ministries or agencies invest in adaptation, who receives resources, and what actions are being funded. This underlying accountability infrastructure is necessary for money to be channeled to communities, including the poorest and most vulnerable who are on the front lines of climate change and have a vital role to play in informing adaptation planning.

Nisha Krishnan is a climate finance associate for Climate Resilience Practice at the World Resources Institute (WRI). Stefanie Tye is a research analyst, while Marlena Chertock is a communications specialist for Governance at WRI. This post is republished from the WRI blog.