As popular travel destinations have reopened, or prepare to reopen for international tourism, it remains to be seen whether the coronavirus will serve as a wake-up call to advance the decarbonisation of tourism, or whether sustainability will take a backseat to economic recovery.

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

The tourism industry has been heavily impacted by the pandemic. Globally, tourist arrivals suffered a 22 per cent drop in the first three months of 2020—the equivalent of $80 billion in lost tourist receipts.

The Asia-Pacific region was the worst hit with 33 million fewer arrivals. With international travel projected to decline by as much as 60-80 per cent in 2020, the World Tourism Organization (UNWTO) predicts that 100 to 120 million jobs in tourism are at risk.

On the flip side, the short-term environmental benefits of COVID-19 are undeniable: increased sightings of wildlife species, improved air quality and declining carbon emissions. The pandemic alone cannot, however, stop climate change.

“In the developed world, the effects of the coronavirus on our natural world have been largely positive: carbon dioxide emissions have dropped, leatherback turtles are nesting in Phuket and Florida, and more people are becoming aware of the real cost of the wildlife trade,” said Marit Miners, co-founder of Misool, an eco-resort in Raja Ampat, Indonesia.

“However, in the developing world, an entirely different set of levers and knobs determine conservation outcomes,” she added.

Ecotourism—and conservation efforts—at risk

Organisations that rely on visitors to fund conservation projects, or to employ and support local communities, have been dealt a devastating blow, as declining revenue and cuts in external funding hinder their ability to finance law enforcement activities and staff salaries.

The Misool patrol crew. Image: Shawn Heinrichs

Reduced or suspended patrolling has led to a surge in illicit activities, including poaching, illegal fishing or deforestation, especially as community members who have lost their source of income because of the pandemic have few other alternatives.

Efforts to combat illegal fishing in Indonesia have also been impacted by a slash of more than a quarter in government funding, as resources were redirected to fight Covid-19.

As a stark example, on a routine patrol in April 2020, the Misool team encountered three commercial boats fishing illegally inside the Misool Marine Reserve—not too far from Magic Mountain, an ecologically sensitive sea mount and cleaning station for both oceanic and reef manta rays.

“These poachers were 165 km away from home, equipped with GPS and depth sounders, taking advantage of the sudden vacuum created by the collapse in tourism,” Miners explained. “With the support of marine police, our team confiscated 150 kg of fish, including groupers, giant trevally, and red snappers.”

Eco-tourism key to local livelihoods and community engagement

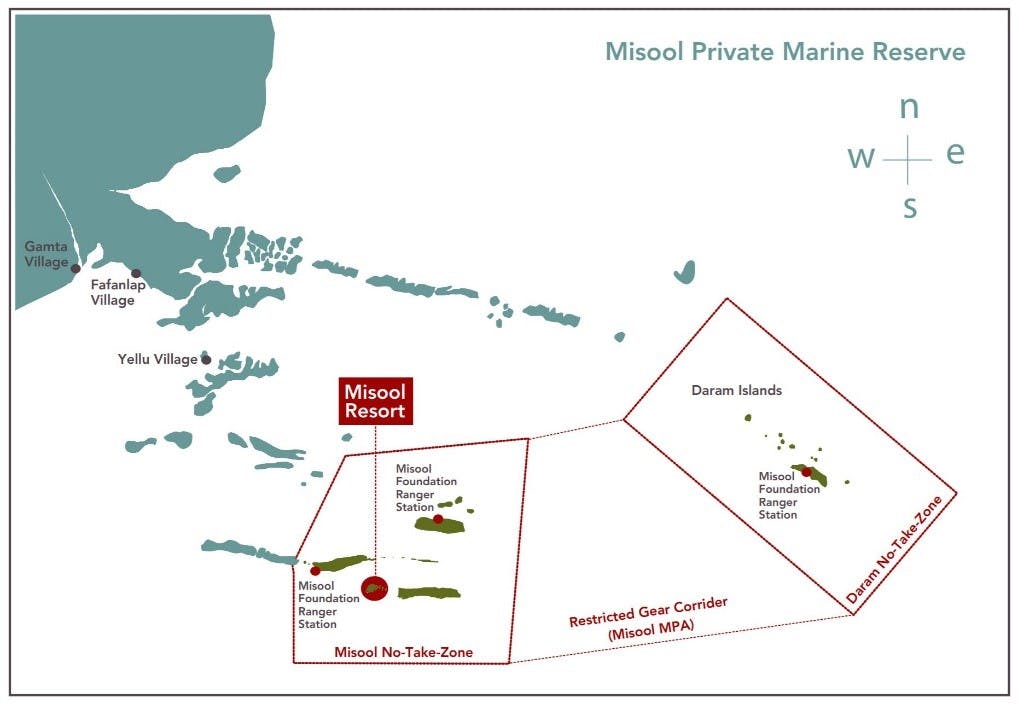

Misool, which opened its doors in 2008, does not only provide a crucial source of employment in the region, but partnered with the local community to create a no-take zone in what used to be a notorious shark-hunting ground. This means no fishing, no collecting of turtle eggs, no reef bombing, and no netting. It also operates a patrol team with members of the community, the local marine police and the army to enforce the fishing ban.

The 300,000-acre Misool Marine Reserve protects complex coral reef systems and deepwater areas in Raja Ampat, Indonesia. Image: Misool

Employing and directly engaging local communities in conservation efforts are critical to ensure that those who call your latest travel destination their home can reap the socio-economic and environmental benefits of responsible tourism.

“Before Misool was established, there was nothing to stop people from the community and outsiders from catching any marine animals that they chose. They could fish without restrictions, even using dynamite fishing in some places,” shared village elder Bapak Mohammad, who was one of the resort’s first employees and the founder of its charitable arm, the Misool Foundation.

“Part of what I do is to act as a bridge between the resort, the foundation and the community to help them to understand each other’s needs. At first, fishermen did not welcome the idea of a no-take-zone, however, as they started to see the changes in the environment, they began to understand that the future for their children is brighter now that the reefs are protected.”

Tourism as a critical funding source for conservation

Before the official registration of the Misool Foundation in 2011, the resort was the sole funder of the conservation and law enforcement efforts in the area. Foundation initiatives include coral restoration, manta and mobula ray research and conservation, community recycling and early childhood education.

Early childhood education on environmental issues is one of the key initiatives launched by the Misool Foundation as part of the organisation’s conservation efforts. Image: Pambajeng Putro Otomo

When they first came across the abandoned shark-finning camp in 2005, Miners and her husband had planned to create a conservation centre with no thoughts of opening a resort. They quickly recognised, however, that without the financing and human resources of a profitable commercial enterprise, they would be unable to sustain their conservation efforts on the long term.

The fishing ban and the conservation programmes enabled a 250 per cent increase in biomass in the span of six years (2007-2013) in the resort’s 300,000-acre marine reserve, including more fish species than anywhere in the world, and 25 times more sharks in the protected area than directly outside.

Misool’s example demonstrates that tourism can provide a crucial funding vehicle for conservation and that recovery for the sector and for nature must go hand in hand.

A responsible recovery for tourism

Ultimately, the industry must leverage the current health and economic crisis as an opportunity to rebuild in a more sustainable manner.

“Sustainability must no longer be a niche part of tourism but must be the new norm for every part of our sector”, said Zurab Pololikashvili, Secretary-General at the UNWTO as he unveiled the One Planet Vision for the Responsible Recovery of the Tourism Sector. “It is in our hands to transform tourism and that emerging from COVID-19 becomes a turning point for sustainability.”

Hygiene measures should balance health and safety with sustainability, without leading to excessive use of single-use items instead of reusables, or harmful pollutants instead of eco-friendly disinfectants.

Social distancing protocols must not limit accessibility for the elderly or people with disabilities.

Responsible recovery must include targeted support to vulnerable communities, including women, the youth, rural or indigenous populations, who have been especially hard hit by the pandemic due to their reliance on tourism as a main source of livelihood. They also typically work in the informal economy, with no social protection or health and safety measures at work, and are often excluded from Covid-19-related financial assistance programmes.

Businesses should consider measures to cut their carbon footprint and integrate circular economy processes to ‘build back better’. In the words of a recent campaign launched by Misool, together with actress Bo Derek and marine conservationist Shawn Heinrichs, we must ‘come back slowly’, and place sustainability at the heart of economic recovery.