Today, all that burning of oil, coal and natural gas has warmed the planet toward dangerous levels, and science shows that fossil fuel use must decline to slow climate change. At the same time, more than 40 per cent of the global population survives on less than US$5.50 a day, primarily in developing countries.

Fossil fuels are still among the cheapest ways to power economic growth, making them hard for developing countries to ignore.

So, can we find a way to lift nearly half of the world out of poverty and still reduce fossil fuel use? As an environmental social scientist, I believe there can be no sustainable development, and likely no energy transition, if poverty is not addressed too. Current international efforts, like the chronically underfunded U.N. Green Climate Fund, whose board meets this week, aren’t doing enough.

Shadows of colonialism

The fact that nearly half the world’s population is still struggling to escape poverty while the thermometer’s mercury hurtles upward is not a coincidence.

Since the Age of Discovery, when European explorers began expanding trade and claiming colonies in the 1400s, problems of resource scarcity have been managed through colonial conquest and economic integration. These approaches impoverished Global South nations, robbing them of their natural wealth. The introduction of international financial institutions after World War II further locked them into a cycle of uneven exchange.

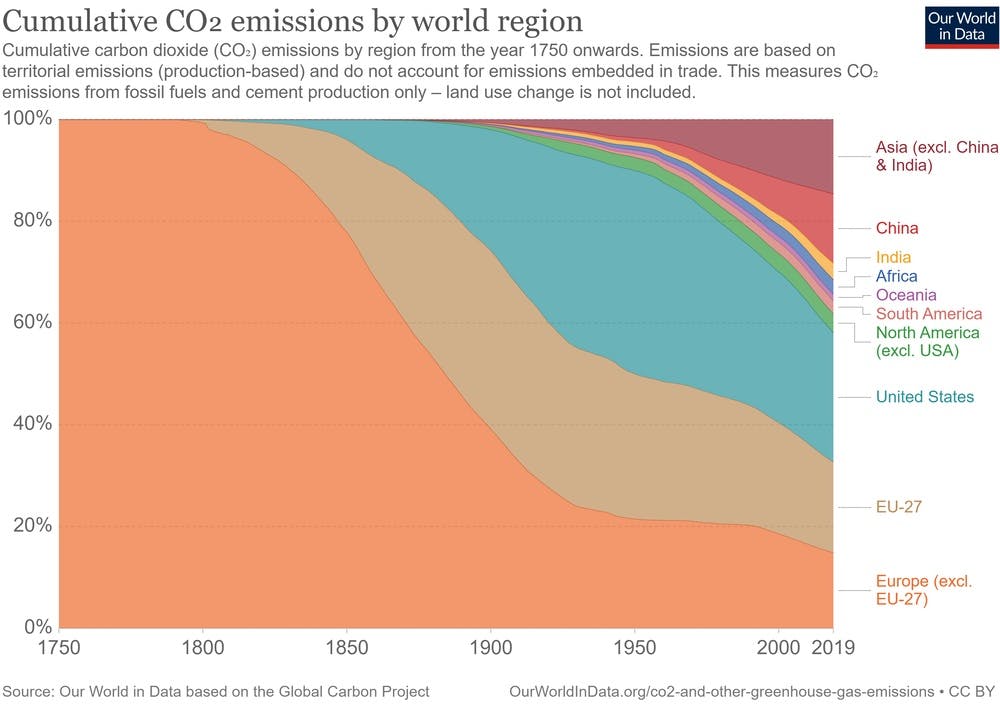

For hundreds of years the natural resources that southern nations exported to countries like Germany and the United States have been sold at a lower cost than the finished products they import for their own consumption. The result has been development in the Global North, destabilisation and impoverishment in much of the Global South and climate change for all.

Fossil fuels have been a central element in development history because they have provided a cheap, mobile source of energy. They still predominantly boost wealthy countries’ growth. In 2019, the 37 nations belonging to the Organisation of Economic Cooperation and Development, which represents industrialised economies, still accounted for a staggering 40 per cent of energy consumption. The remaining 60 per cent was spread across 158 countries whose combined populations were 5.83 times as large as those of Organisation of Economic Cooperation and Development nations.

Without a rapid transition to renewable energy, it is unlikely that populations outside the Organisation of Economic Cooperation and Development will be able to use energy as freely as others have while still keeping global temperature increases below 1.5 C (2.7 F), the goal countries set under the Paris climate agreement.

‘Development is not a right’

The inequalities born of these processes make stopping the drivers of climate change a real challenge.

Southern nations rightly insist that viable climate solutions must include a realistic pathway for them to continue to develop. This resulted in three principles included in the 1992 Rio Declaration on Environment and Development: that countries have a right to development, that the development needs of developing countries should be prioritised and that nations have a “common but differentiated responsibility” to address the dual problems of global development and climate change.

Women in South Africa fill wheelbarrows with free coal in 2015. Their settlement lacked access to the electricity grid, despite being less than two miles from an Eskom powr plant. Marco Longari/AFP via Getty Images

The U.S. famously rejected these principles during the George H.W. Bush administration, stating that “development is not a right.” That statement reflected a general concern among wealthy nations that they might be held financially responsible for ensuring the continued development of poorer nations.

The Green Climate Fund

In 2010, the recognition of ongoing injustices resulted in the creation of the Green Climate Fund.

The U.N. launched the fund with the goal that wealthy countries would voluntarily mobilise US$100 billion a year to support climate projects in developing countries and help enable them to pursue their development interests. But the Green Climate Fund has never been funded at more than US$9 billion a year.

While the Biden administration’s pledge to provide the Green Climate Fund with US$5.7 billion annually is a dramatic improvement, in my view it is still far from adequate. The wealthy G-7 nations, at their meeting in June 2021, recommitted themselves to the US$100 billion goal, but that is only a statement so far.

Historically, it has been difficult to displace cheap and readily available energy sources like fossil fuels in the presence of poverty and systematised economic inequality. Instead of energy transitions, countries made energy additions. My research with Julius McGee has found that nations with greater economic inequality have used renewable energy to carry electricity to underserved populations, increasing access to electricity, but they have not reduced overall fossil fuel use.

With more support to help cover the high upfront investments, the falling costs of renewable energy could help developing countries take meaningful steps toward the eradication of poverty without relying on carbon-packed sources of energy to do so. But that alone will not be enough.

Source: Our World in Data based on the Global Carbon Project

Trying to set limits in a fair way

The most effective path for allowing poorer countries to develop while the world reduces greenhouse gas emissions may be what’s known as contraction and convergence.

First introduced by India in 1995, the framework is meant to encourage the adoption of policies that would lead to an overall contraction in global emissions. Wealthier nations would cut their emissions, while poorer countries could continue increasing their emissions as they build the social and economic infrastructure to lift their populations out of poverty. Eventually, poorer nations would begin to reduce their emissions as well.

Ultimately, helping poorer countries develop in sustainable ways is in the interest of wealthier populations too, because climate change will affect lives everywhere. Ignoring the glaring social inequalities of past development and current responses to climate change ensures that much of the globe’s population will believe they have little choice but to lean on fossil fuels as they develop, and slowing global emissions may come far too late.

[Get our best science, health and technology stories. Sign up for The Conversation’s science newsletter.]

Patrick Greiner, Assistant Professor of Sociology, Vanderbilt University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.