The global seafood market faces turmoil with the release of the Fukushima nuclear wastewater from Japan into the Pacific Ocean, computer modelling predicts.

Japan announced in 2021 it will release over 1.25 million tonnes of treated Fukushima radioactive wastewater into the sea as part of its plan to decommission the power station when its storage capacity reaches its limit this year.

Seafood is one of the most important food commodities in international trade, far exceeding meat and milk products. According to the United Nations Comtrade database, global seafood trade has grown from USD$7.57 billion in 2009 to USD$12.36 billion in 2019, an increase of 63.2 per cent.

The Japanese nuclear wastewater discharge raises global worries about the safety of Japanese seafood as public opinion influences consumers’ preference for seafood.

In this empirical study involving American consumers, 30 percent of respondents said they reduced their seafood consumption following the Fukushima nuclear plant accident and more than half believe Asian seafood poses a risk to consumer health due to the disaster.

Most of Japan’s seafood trading partners, such as China, Russia, India and South Korea, imposed temporary bans on food from several districts around Fukushima in wake of the accident in 2011.

This paper models the potential impact of the Fukushima nuclear wastewater disposal on the global seafood trade using the import and export data for 26 countries which make up more than 92 percent of the world’s trade in marine products.

A community classification theory of complex networks was used to classify seafood trading countries into three communities. Seafood trade is frequent among countries within each individual community and less between the communities.

The first community contains Ecuador, Italy, Morocco, Portugal and Spain. The second contains Denmark, France, Germany, Iceland, New Zealand, Nigeria, Norway, Poland, Sweden, and the United Kingdom.

The third community contains China, India, Indonesia, Japan, South Korea, Malaysia, Taiwan of China, Russia, Thailand, the United States and Vietnam.

Modelling shows China, South Korea, and the US maintain a steady trade of seafood imports and exports between them. Data used for the modelling shows that the rate of change in trade between China and Korea, China and the US and between Korea and the US is very close to zero.

However, China, South Korea and the US are expected to increase their seafood imports from Denmark, France, Norway and other community group two countries while reducing seafood exports to them. This is because these three countries have already reduced their seafood trade with Japan.

The increase in exports from community group three to community group two nations leads to a decrease in imports and exports between countries within community group two. For example, the study notes that Denmark, Norway and France are all experiencing a decrease in seafood exports and imports between each other.

While the rates of change in trade between countries look very close, the size of each country’s import and export market is different, so the actual trade volume can vary greatly.

The model also divided the global seafood market into two segments — the first being the Japanese market and the second comprising 25 other countries. It calculated that Japan’s seafood exports fell by 19 per cent in 2021, or USD$259 million.

Public opinion after the Fukushima wastewater is discharged will have different impacts on the import and export trade of seafood for each country, especially for countries which trade with Japan.

What people think (about the discharge) is closely related to the amount of Japanese seafood imported by each country. The higher the amount of Japanese seafood imported by a particular country, the more negative public opinion is likely to be, according to computer modelling.

Japanese imports of seafood will also be reduced, predicts the computer model. However, the amount of reduction depends on how well the Japanese public accepts local seafood after the discharge of the nuclear wastewater.

The Japanese government has announced it will spend USD$260 million to buy local seafood products if domestic sales are affected by the release of Fukushima wastewater.

If the Japanese public is more accepting of seafood caught in waters around the discharge area, seafood imports from other countries to Japan will likely fall. However, if public opinion does not go this way, Japan will have to import more seafood to meet local demand.

If 40 per cent of the reduction in Japanese seafood exports is absorbed by its own market, the modelling shows this would result in a USD$272 million reduction in Japanese seafood imports from other countries.

Image: UN Comtrade Database, 2021. Ming Wang, Dalian Maritime University

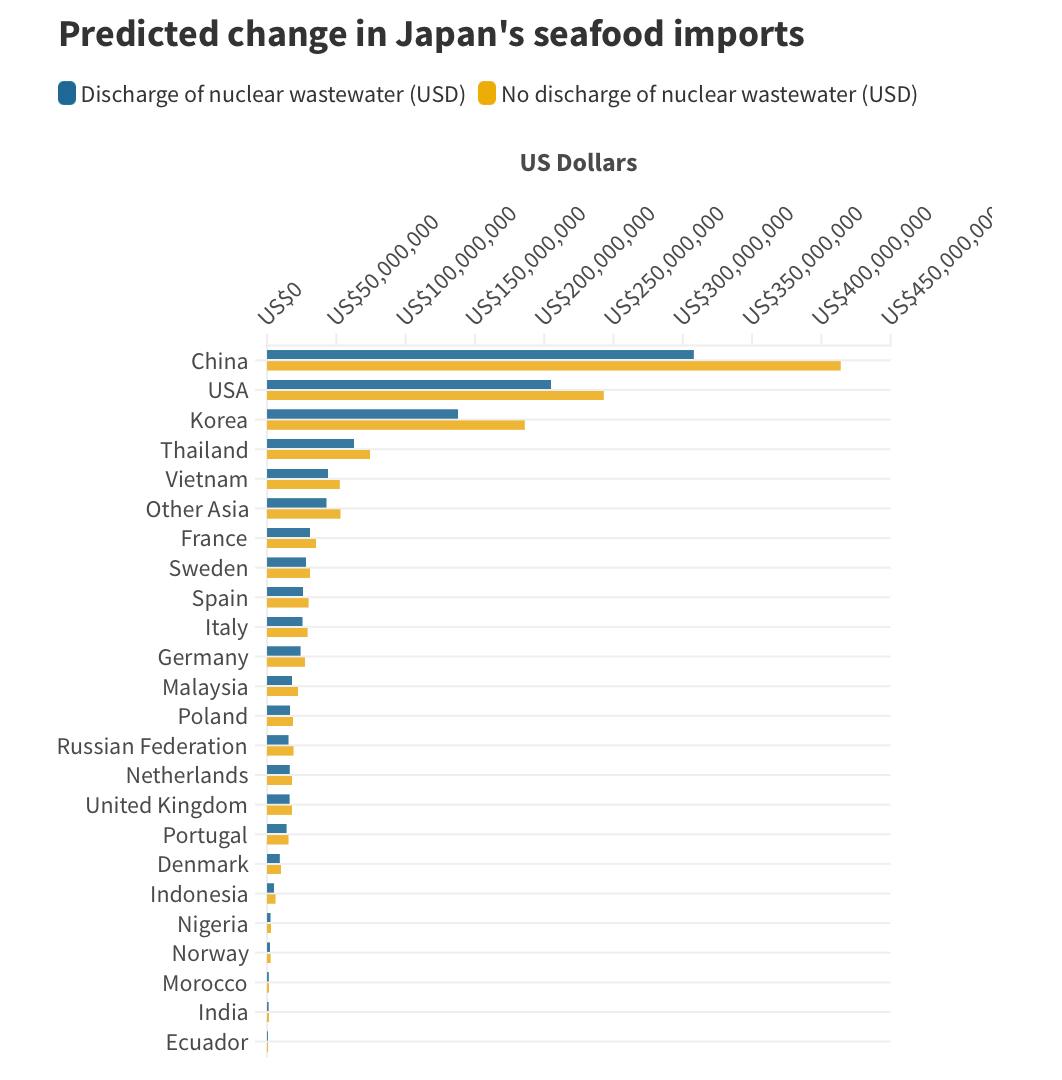

The above table from the computer model shows the predicted decrease in the trade volume of seafood exports from 25 countries to Japan. The impact of seafood exported to Japan is also related to the community classification.

Countries in the same community as Japan show a more significant reduction in their seafood exports to Japan while countries not in the same community have less impact. The planned Fukushima nuclear wastewater disposal will mainly affect countries in the same seafood trading community as Japan.

These countries will see more significant reductions in their imports of Japanese seafood and in the exports of their seafood to Japan compared to countries in other communities.

Ming Wang is a doctoral student in econometrics, complex networks and multi-modal transportation at the School of Maritime Economics and Management, Dalian Maritime University, China. He declares no conflict of interest.

Originally published under Creative Commons by 360info™.