In the Sungai Asap settlement in Sarawak, social distancing is near impossible. This ramshackle town 2 hours east of Bintulu is home to thousands of indigenous people displaced in the early 2000s to make way for a mega-dam.

Living in communal longhouses, often with bathrooms and kitchens shared amongst extended family, an outbreak of coronavirus would be disastrous.

Medical facilities here are already stretched, with one small clinic serving the 10,000 strong community. “There’s only one ambulance.” explains Miku Loyang, a local carver of poison blowpipes.

“If someone is sick enough to need an ambulance, they wait until another sick person comes along so they’re not wasting the drive. Too bad if you’re having a heart attack.”

Further into Borneo’s interior, logging companies continue to extract timber, according to Penan headman Komeok Joe. The state of Sarawak is a world leader in tropical timber extraction, with 80 per cent of its forests degraded within the last few decades.

“

Coronavirus is hitting indigenous communities in Sarawak hard even while the virus is, thankfully, yet to reach them. In order to prevent the next devastating pandemic, policy makers need to be able to see the forest for the trees. Deforestation is a public health issue.

In 2010, more timber was exported from Sarawak than all Latin American and African countries combined. The forests that are left standing—along with the staggering array of wildlife that call them home—remain thanks to communities like Komeok’s.

Unsurprisingly, logging has been classified as essential by the Sarawak government during the lockdown, meaning potentially virus-carrying crews are still venturing into indigenous lands where medical supplies are non-existent.

“Ongoing logging will help spread the virus and is, therefore, an immediate health threat to communities,” says Komeok. This is especially risky in the many communities whose population is made up largely of retirees.

Remote communities would ordinarily protect their unceded lands by putting their bodies on the line, forming a blockade between themselves and the bulldozers, or by reporting illegal loggers to authorities.

Under the Movement Control Order, indigenous villagers have also been told to stay put. While a free-for-all is greenlighted for logging companies, resistance has come to a grinding halt.

In mid-March, Malaysia rolled out one of the swiftest shutdowns in Southeast Asia. The Movement Control Order has left many afraid to leave their homes even for essential reasons, with those who break curfew facing heavy fines and up to 6 months in prison.

Kenyah leader Peter Kallang is concerned about how remote communities will cope with complete shutdown. “Indigenous communities need to travel to town to get coffee, milk powder, sugar, flour and tea. You can’t get these essentials from the jungle supermarket,” he says, referring to the hunting and gathering that forms the majority of food for traditional indigenous villages in Sarawak.

“Rural communities still need to travel to the nearest town to buy these things, even if doing so poses a threat to their safety”.

Seemingly lost in the Malaysian debate is the growing evidence that diseases such as Covid-19 emerge from the way humans interact with the natural world. It is not just a story of wayward bats or infected pangolins, the coronavirus crisis is a story of tropical rainforest destruction.

Zoonotic diseases such as Covid-19 could be caused by the very industries that are being protected from shutdown. These activities disturb the ecosystems where diseases live, forcing animals out and humans in, increasing interaction between species.

Another pandemic caused by human and wildlife interaction is not far-fetched—Malaysia has already created one epidemic-level virus through environmental degradation and mismanagement.

The 1998 Nipah outbreak has been linked to fruit bat displacement, with slash and burn deforestation to make way for industrial planting pushing the bats into areas with pig farms. This is also the plot of the movie Contagion.

If the coronavirus has shown us anything, it is that reality is stranger than fiction. Previously unthinkable social and economic upheaval has been legislated in a matter of hours all around the world.

Rethinking how we treat our natural environment is not outside the realm of possibility. It might even be a moral imperative.

Outposts like Sungai Asap are starting to receive rations, distributed via logging road and helicopter by army and rescue personnel. But local politicians and NGOs are receiving complaints about the distribution methods and lack of information about eligibility.

“Many hopefuls are not getting it,” DAP Senadin Chairman told The Borneo Post. “This seems to be the case in both rural and town areas. We understand that the budget may not be enough for everyone to get a share.”

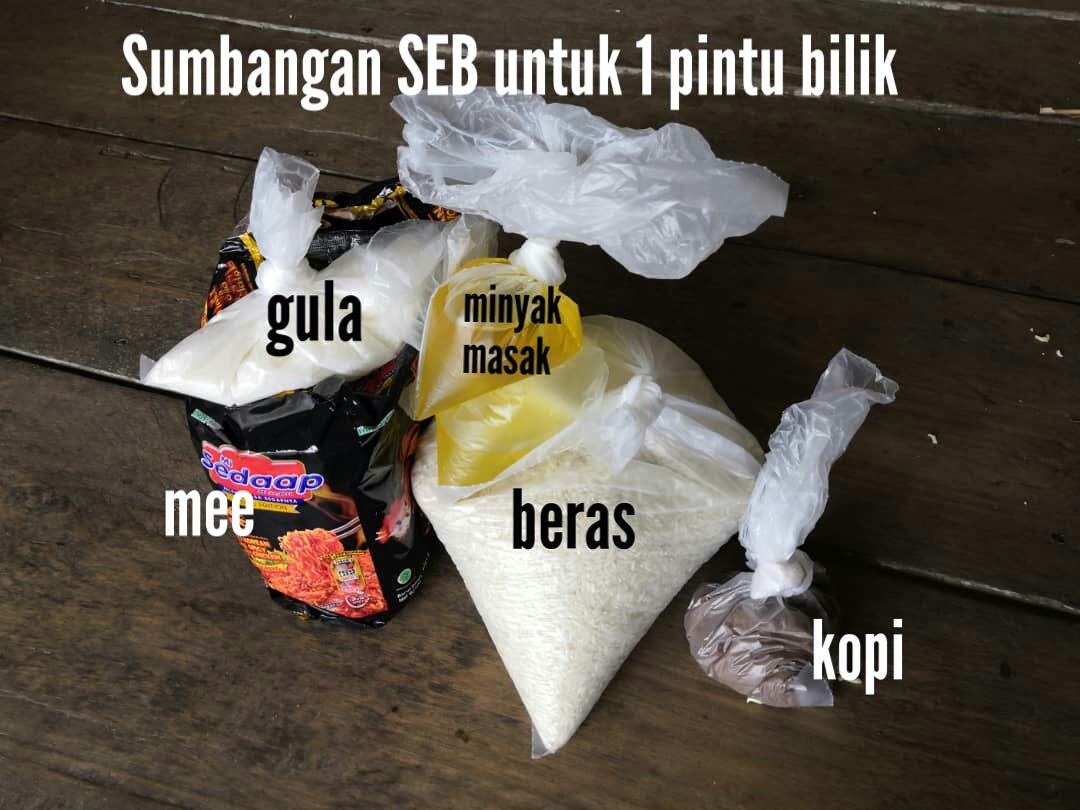

Per family rations of noodles, sugar, oil, rice and coffee distributed by Sarawak Energy Berhad in Sungai Asap, April 2020. Image: SAVE Rivers

While limited rations are worrying, a crackdown on access to wild meat would be a much greater risk to indigenous food security.

Although a shutdown on the trade of wildlife and illegal sale of wild meat to people who have access to other protein could help prevent health crises of the future, banning the capture and consumption of wild animals by subsistence hunters could leave indigenous communities malnourished. As in Sarawak, indigenous people all over the world rely on the forest as their main source of protein.

In response to calls from indigenous leaders to shut down destructive industries, many in Malaysia are pointing to the economic cost of doing so. The cost of leaving palm fruit to spoil would be immense, and the price of timber has reportedly dropped by nearly half within a matter of weeks.

If these industries were to crumble, many would lose their jobs, especially the impoverished Indonesian migrant workers on the bottom rung. But these costs pale in comparison to the trillions that coronavirus has wiped from the global economy. Not to mention the loss of human life around the world.

As if the climate arguments for forest protection and restoration weren’t reason enough, it is hard to argue against the fact that the world can’t afford another coronavirus. Pandemics are bad for business, no matter what that business might be.

Coronavirus is hitting indigenous communities in Sarawak hard even while the virus is, thankfully, yet to reach them. In order to prevent the next devastating pandemic, policy makers need to be able to see the forest for the trees. Deforestation is a public health issue.

We should be halting the destruction of tropical rainforests as a matter of urgency, not exempting the very industries that create the problem.

Fiona McAlpine is Communications and Project Manager for The Borneo Project, a non profit working with indigenous communities in Malaysian Borneo. To find out more about their work head to borneoproject.org