This is part of a series on landscapes. Read Part 1 – Why are Landscapes Important?

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

My previous “why” question was all but rhetoric – everyone I have spoken with agrees that landscapes are hugely important, and also agrees that they are essential for human well-being at large as well as life on our planet.

Asking “What are landscapes?” is more delicate and requires some thought as to where we are aiming with landscape approaches. The way we use “landscape” should be determined by the context we want and solutions we aim for, not the other way around.

The word landscape has been used for hundreds of years to encompass aspects of art, laws and geography. It is not often I quote Wikipedia but, I found this article on “landscape” enlightening, particularly the etymology with several references to landscapes as a social construct. I also note an article by Kenneth Olwig that explores the historical concept in depth, including to say that “A substantive concept of landscape is more concerned with social law and justice than with natural law or aesthetics.”

The concept of landscape approaches for sustainable development has been around for decades. This recent PNAS article by Jeff Sayer, Terry Sunderland et al. provides a good review and also highlights how the UN Convention on Biological Diversity, an intergovernmental process, has recently included the landscape concept in their negotiation process.

“

The aim of a landscapes approach, as we have expressed in the objectives of the Global Landscapes Forum, is to contribute to sustainable development and support actions to curb climate change. This is a tall order

So, where do we take the landscape concept now, given all these experiences from the past?

Coming to a definition

Having worked many years with forest-related definitions, I am well aware how different opinions, positioning, professional affiliations, political agendas and feelings can go into arguments over a definition, such as the one for “forest.”

I am not keen to have the same debate over the definition of “landscape.” What we need is an understanding that is generic and broad enough to include all combinations of forestry, agriculture and other land uses. And we need a definition that encompasses human interests and actions, as well as the biophysical constitution of the landscape. In other words, in defining a landscape we need to include both the landscape extent and resources, as well as society’s interaction with the landscape.

The aim of a landscapes approach, as we have expressed in the objectives of the Global Landscapes Forum, is to contribute to sustainable development and support actions to curb climate change. This is a tall order.

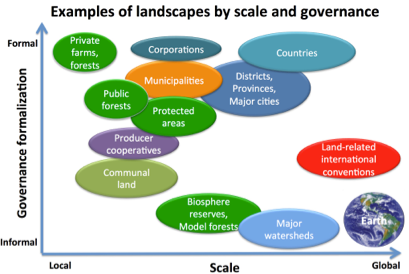

We should therefore define “landscape” in a way that does not exclude any real-world situation. We should also, preferably, define “landscape” so that it can be used across scales. A farm is a landscape. Earth is the ultimate landscape. The concept must apply across this entire range of scale if we are to meet the above objectives.

But we can’t define a landscape only by locating a geographic area and drawing a boundary on a map. It is the human dimension that makes it a landscape. That is, there has to be some form of institution(s) to express ambitions for the geographic area, set priorities and help transform these ambitions into action. We can call this landscape governance and should acknowledge that such governance arrangements can be wildly different and exist as entirely informal as well as strictly formal arrangements.

By those two basic parameters — geographic extent and governance — I propose the following definition:

Landscape = “A place with governance in place”

(1) A place: A landscape is a geographical area that can be of any size — from very small to very large.

(2) with governance in place: There exists institution(s) that will consider options for the landscape and set priorities. The formalization level of this governance can vary, from informal to formal.

The graph above illustrates how different types of landscapes can be mapped into these two dimensions. As you can see, this is a very inclusive way of defining what a landscape is. In fact, it is so inclusive that a given location would always be part of several landscapes of different scales at the same time. This is perfectly fine and also reflects the layers of simultaneous governance situations we find ourselves in.

This discussion of what is meant by a landscape provides a starting point for the next step and the topic of my next blog — discussing how we can determine objectives and measure progress in landscapes in a comparable way across all these situations.