Plastic pollution action has been slowed down considerably by the Covid-19 pandemic – but there’s a new emerging angle that could help rebuild momentum behind our transition to a greener and more circular society. Governments at the World Trade Organization (WTO) are showing increased interest in tackling plastic pollution.

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

In a world of global value chains and integrated markets, there is an important cross-border component, both existing and potential, to ramping up efforts on plastic action. Until recently, limited plastics recycling efforts often involved exports, the overwhelming majority of which flowed to China. These flows have become a source of controversy due to waste dumping and inadequate infrastructure for proper disposal.

In 2018, China introduced a ban on certain plastic waste imports, a move followed by several other countries. Subsequently, in May 2019, the 187 parties to the Basel Convention—a treaty on the transboundary movement and disposal of hazardous and other wastes—added most types of plastic waste to the list of controlled wastes. From 2021, plastic waste that is sorted, clean, uncontaminated and effectively designed for recycling can be traded freely, while other types will require the consent of importing and transit countries.

These changes could prove positive to improve plastic waste management and reduce leakage into the environment. Yet, without additional implementation efforts, a risk of increased trade frictions develops that could stymie global plastics recycling markets. Such frictions have not developed to date, but trade facilitation measures to aid reduction and re-use have also not been enough in focus.

The World Economic Forum recently gathered a group of experts from consumer goods brands, industries, governments and civil society to discuss the role that trade could play in advancing action on plastic pollution. The result of that initial cross-sector discussion—as well as the many that followed—have led to a new community paper that outlines trade barriers to accelerating action on plastic pollution.

We hope that trade policymakers and environment practitioners alike will find this paper a helpful resource to aid their discussions and promote new supportive actions for the 3Rs—reduce, re-use and recycle.

1. Domestic bans and slow approvals curb recycled plastic use

Countries’ regulations determine which items can be brought into a market. In addition to bans on plastic waste imports, several countries have implemented more complex rules on high-quality recycling plastic imports, which limits the use of recycled plastic packaging. Further, in other cases, manufacturers have had to switch to virgin plastic inputs for certain consumer goods, as the same quality of recycled plastic could not be sourced in the domestic market. Some markets have slow regulatory approval processes regarding the use of recycled plastic products.

2. Diverse standards and limited data are complicating circular supply chains

In a world of value chains, differences in standards create challenges – whether on recycled plastic production, use or labelling. Varying grades of plastic by producers require recyclers to create different recycled plastic grades that add to costs. Missing information on materials’ properties complicates recycling processes since certain additives can pose risks to human or ecological health during the mechanical recycling process.

The absence of traceability and data shortages, meanwhile, creates uncertainty on what materials are where in the market—especially for recycled content.

3. More efforts are needed to facilitate circular plastics investments worldwide

Part of the challenge in building a circular plastics economy lies in insufficient investment upstream and downstream in emerging and advanced economies alike. There is a need to incubate and scale innovations and new ventures – including new material design and new businesses models – and to close the operational financing gap for city-level waste collection and recycling systems while mobilising capital investments for circular options and waste management more broadly.

Circular plastics investments can be slowed down or sped up based on several factors, not least the regulatory environment, local infrastructure and skills, incentives, government procurement policies and overall investment assistance. Facilitating and attracting investment in sustainable plastic solutions by matching solution providers with public and private funding opportunities will also help to close this gap.

4. Processes

From 2021, most plastic waste trade will be subject to the Basel Convention prior informed consent (PIC) procedure as controlled waste. Interviews with companies highlighted that to date some countries lack the capacity to efficiently review and process PIC notifications. In many cases, documents are still in paper format causing long delays in shipments.

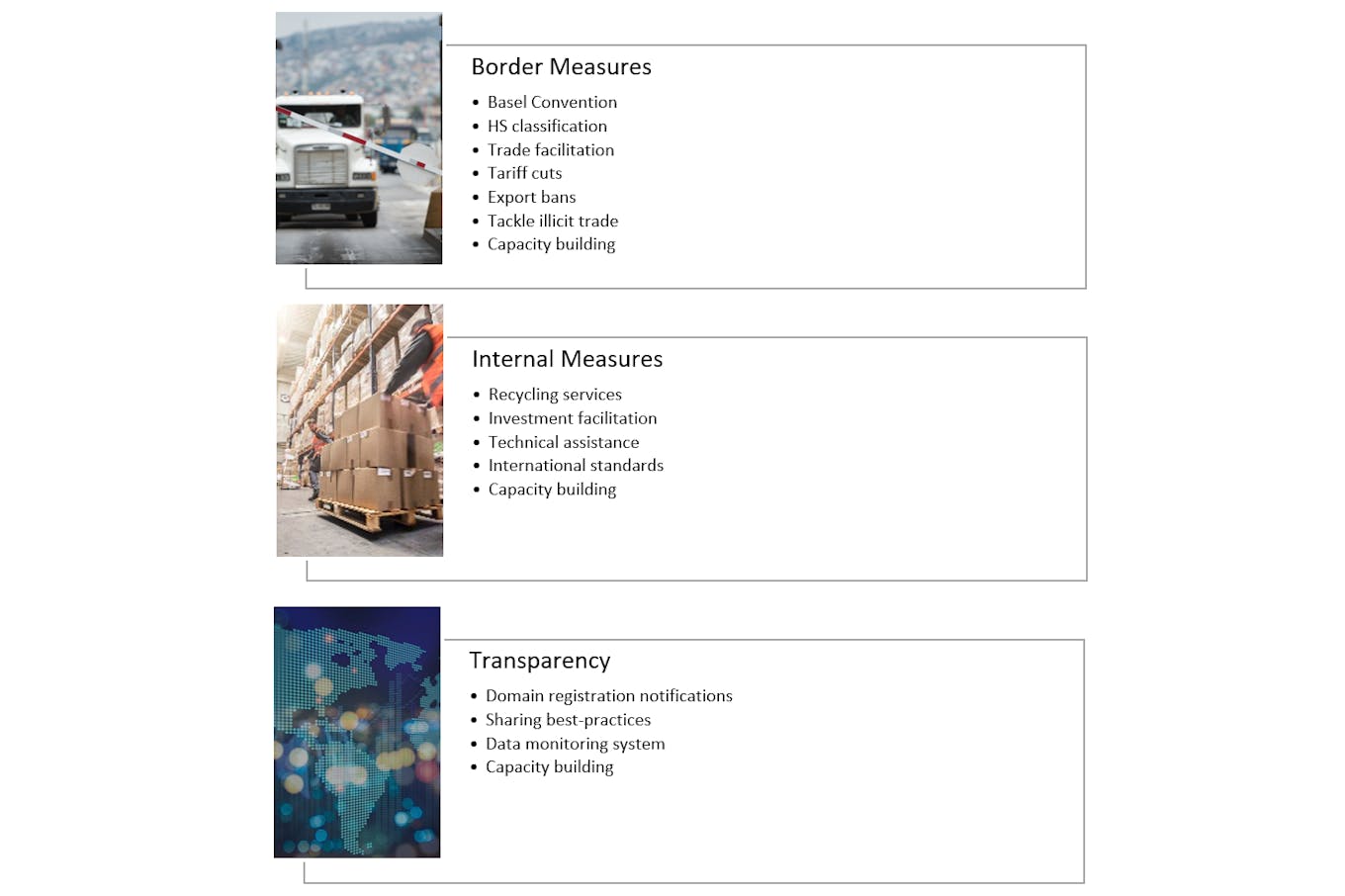

So, what role can trade policy and capacity building play in tackling these challenges? Our community put forward ideas for further exploration in three areas, complemented by regulatory cooperation:

1. Border measures

Efforts can be made to refine the Harmonized System (HS) classifications, an international classification for traded goods, which does not yet distinguish between hard- and easy-to-recycle plastic waste, nor between virgin and recycled plastics. Doing so could help ensure traded waste for circular economy objectives is more easily identified and policies adapted. The Basel Convention secretariat is drafting proposed amendments in this space.

For example, trade in easy-to-recycle plastics could be encouraged by placing lower tariffs on these specific kinds of plastics. Countries could equally ban exports of plastic types that are restricted domestically to avoid the dumping of lower-quality materials in foreign markets.

Links could be made between capacity building around the WTO Trade Facilitation Agreement (TFA) and digitising the PIC procedure. Countries have shown some appetite to move to electronic and automated notification for PIC requirements, but it is important to avoid running electronic and paper systems simultaneously.

Work could also be undertaken between countries and companies to pinpoint the weak points in the system that are driving illegal trade for plastic waste dumping. The Global Plastic Action Partnership (GPAP) will be taking a close look at how we can facilitate this type of collaboration as a platform for key industry leaders and decision-makers.

2. Internal measures

Some policies operate away from the border but nonetheless have an impact on trade flows and investment decisions. Trade commitments can be used to enable foreign services providers to offer recycling services within a market and grant them the same treatment as national players to create competition. Work could be done on facilitating investment, including financial or regulatory incentives for production and consumption of recycled plastics.

The agreement of international standards in related areas can be promoted through trade policy as a guide for domestic regulatory initiatives to avoid arbitrary discrimination and promote convergence.

3. Transparency

Transparency on domestic measures is critical for businesses to engage in trade and develop cross-border markets. Countries could agree, whether at a global level through the WTO or elsewhere, to share information on trade-related measures and sustainability standards relevant to plastic production, waste and recycling.

Data sharing on recycling rates as well as monitoring and analysis of trends in global recycled plastic production would also be helpful. Similarly, there is a need for improved trade and cross-border flows of plastics and plastic waste at a sufficiently disaggregated level (facilitated by a refined HS classification system).

Internal measures such as investment facilitation could stimulate advancements in the circular plastics economy. Creating a regulatory environment that increases transparency, consistency, and lowers risk will encourage investments in both developing and advanced economies and will support the procurement of resources for more robust internal waste management facilities.

Increased transparency by means of data collection and monitoring is key—an area of focus for GPAP. Creating publicly accessible digital systems on cross-border plastics flows will allow governments to better tackle illicit activity and provide more accurate statistics on plastics recovery and recycling rates.

Governments can use a range of different trade instruments to advance these ideas. At a global level, some WTO members have shown interest in launching a new initiative, while free trade agreements (FTAs) are another option. Regulatory cooperation—whether on standards, rules on materials treatment or on chemical governance—will also be critical. Trade policy can support a scale-up of the circular economy for plastics both upstream and downstream. These opportunities should be seized to reset the global economy for sustainable development.

Kristin Hughes is director of Global Plastic Action Partnership and member of the Executive Committee of the World Economic Forum Geneva.

Kimberley Botwright is the Community Lead, Global Trade and Investment at the World Economic Forum.