Women may “hold up half the sky,” as China’s founding father Mao Zedong once famously declared, but when it comes to climate change, they take more than their fair share of suffering.

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

According to a United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) report on Gender and Climate Change in 2013, women and children make up the majority of the 200 million people affected and 70,000 casualties that are caused by natural disasters worldwide.

Finding strategies to protect women in environmentally vulnerable regions is not only an urgent imperative, it also has a beneficial effect on society because of their roles as caregivers who secure food and water for their families.

Highlighting this in her message to commemorate International Women’s Day (IWD) this year, UN Women executive director Phumzile Mlambo-Ngcuka points out that “women and girls are critical to finding sustainable solutions to the challenges of poverty, inequality and the recovery of the communities hardest hit by conflicts, disasters and displacements.”

Celebrated on March 8, International Women’s Day, in a large way, celebrates the ecofeminist idea that the key to solving the global problems of climate change and environmental degradation lies in the empowerment of women, specifically those most affected by the exploitation of natural resources, such as in the developing world.

What is “ecofeminism”?

Coined by French writer Francois d’Eaubonne in her book Le Féminisme ou la Mort (1974), the term “ecofeminism” was a way to label the convergence of the social movements that gained momentum in the 1960s.

Activists fighting for gender equality were aligned with those who sought protection and conservation of the environment, and their goals came together in the struggle to develop narratives and power structures that were not male-dominated.

The theory of ecofeminism is based on the perceived affinity between women and nature, where the oppression and degrading of one – often by societal, “masculine” forces and structures – leads to the disenfranchisement and destruction of the other. Women and nature, in ecofeminism, are seen as intertwined and inseparable entities.

The assumption that there is an inextricable relationship between women and nature comes partly from the symbolic connection that the two share. The language used to describe nature is often feminised, for instance, with terms such as Mother Nature, barren, fertile or virgin; and women are often “naturised”, as when they are described in animal terms as birds, chicks, or bitches.

Throughout history, the domination over women is also paralleled in the domination over nature, particularly during the industrial age (late 18th to 19th century) which was heralded by the invention of the steam engine and its many applications.

Modern science of that period provided more efficient, mechanised and unchecked ways to exploit nature by systematically depleting resources and causing pollution. It similarly marginalised women by keeping fields of knowledge and the benefits afforded by this knowledge (such as wealth and power) the exclusive domain of men.

But beyond these symbolic and historical concepts of connection between women and nature, ecofeminism also sees a parallel between the level and type of damage both suffer as a result of patriarchal systems as well as climate change.

In their book Ecofeminism (1993), authors Vandana Shiva, a pioneer activist from India, and German feminist scholar Maria Mies explain that everywhere, women have been the first to protest against environmental destruction.

“As activists in the ecology movements, it became clear to us that science and technology were not gender neutral…we began to see that the relationship of exploitative dominance between man and nature, and the exploitative and oppressive relationship between men and women prevails in most patriarchal societies, even modern industrial ones, were closely connected,” they write.

In other words, the authors charge that the exploitation of natural resources that contribute to global warming are analogous to the abuse and deprivation suffered by women under the same male-dominated structures and practices that enable capitalistic expansion.

For one thing, there is evidence that in the developing world, the already disadvantaged female suffers more than the male whenever the environment is compromised.

According the same Gender and Climate Change report by UNDP “women—particularly those in poor countries—will be affected differently than men. They are among the most vulnerable to climate change, partly because in many countries they make up the larger share of the agricultural work force and partly because they tend to have access to fewer income-earning opportunities.”

Significantly, the report also notes that “this cycle of deprivation, poverty and inequality undermines the social capital needed to deal effectively with climate change.”

International Women’s Day

Ecofeminism has demonstrated that gender-sensitive approaches to solving problems can have a ripple effect throughout a community.

The theory provides a way to understand the ways in which the fates of women worldwide are tied to the state of the planet, and how improving women’s lives will help alleviate some of the damage that climate change and systemic political and social oppression have wrought.

Part of the improvement, as posited by ecofeminism, involves finding a new status quo with a more gender-balanced order through various means. This is directly aligned with the International Women’s Day 2016 campaign theme, #PledgeforParity: it is a way for the public to commit to making change “for gender-balanced leadership, to respect and value difference, and develop more inclusive and flexible cultures or root out workplace bias.”

One key way of achieving this gender-balanced order is through education. It is the reason that organisations such as United Nations Children’s Emergency Fund (UNICEF) and United Nations Girls’ Education Initiative (UNGEI) actively promote and expand schooling for girls in developing regions.

As UNICEF’s communications specialist Maritza Ascencios says, “Educating girls is a surefire way to raise economic productivity, lower infant and maternal mortality, improve nutritional status and health, reduce poverty, and wipe out HIV/AIDS and other diseases.”

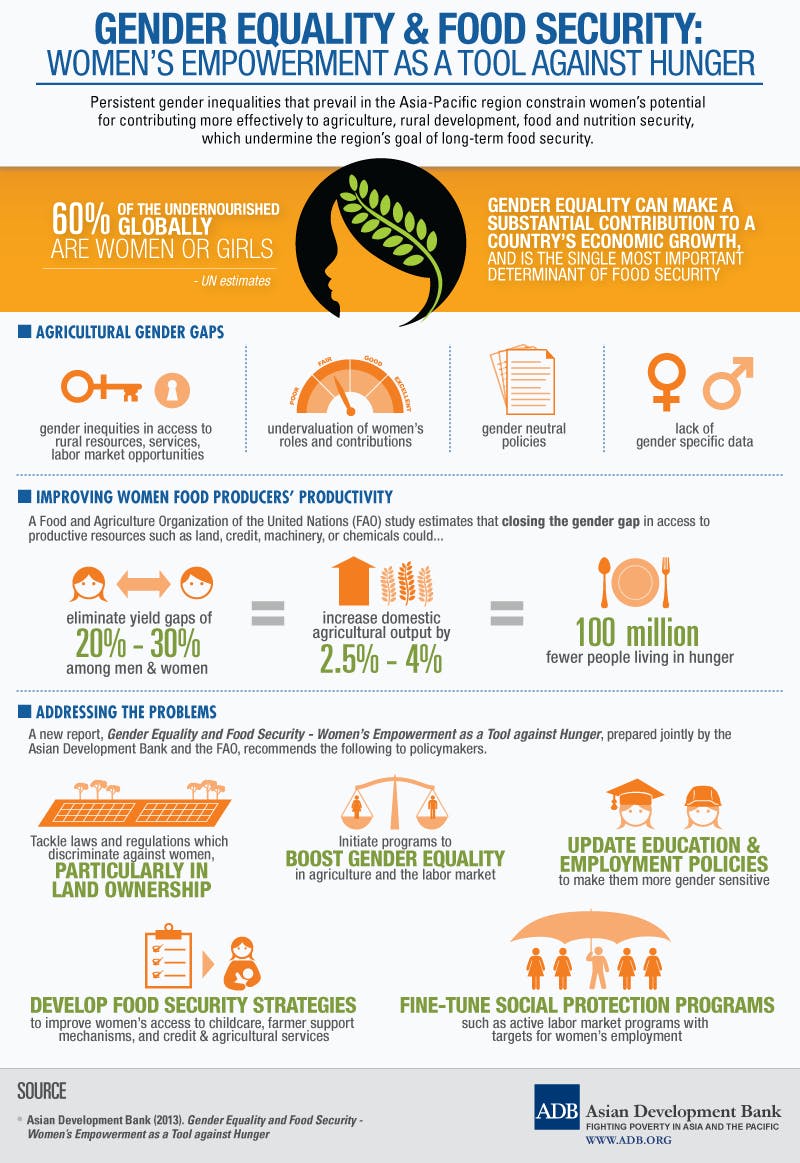

The equality gap addressed by ecofeminism is another way to target global problems, as shown in a report by Asian Development Bank published in 2013, which demonstrates a direct link between empowering women and gender parity with the elimination of hunger.

This infographic lays out the various benefits to be gleaned from achieving gender parity. Image: Asian Development Bank

Besides providing educational opportunities for girls and women to improve gender parity, directly channelling funds to foster entrepreneurial endeavours by women can also vastly improve their lives and communities.

Micro-lending organisation Kiva, for example, notes recognises that “women reinvest 80% of their income in the well-being and education of their families” and is focusing much of their lending programme on supporting women’s entrepreneurial efforts in both developing and developed countries to commemorate International Women’s Day.

Ecofeminism in popular culture

While firmly rooted in social activism and theoretical assumptions, ecofeminism as a way to think about the modern world has become ubiquitous enough to be folded into themes and narratives in mainstream culture.

For instance, the recent Hollywood hit “Mad Max: Fury Road” (released 2015, dir. George Miller), which garnered six Academy Awards at the Oscars last month, made headlines for its feminist take on survival in a post-apocalyptic world.

Whether intentional or not, Miller’s film can be seen as a study of ecofeminism; its narrative framework is a broad guide to the relationship between women, nature and the ecological movement.

In the film, director George Miller’s vision of an apocalyptic wasteland is a dusty, bleak war zone where water is scarce and humanity even rarer, a veritable dystopic vision of ecological exploitation and destruction.

While Max is the protagonist, the story belongs more to Infuriosa, the female warrior-leader whose quest for redemption becomes Max’s own as he gets swept up in her efforts to dismantle the stronghold of Immortan Joe, who hoards water as tyrannically as he does women, whom he uses as “breeders”.

Head shorn and wearing a prosthetic arm, Infuriosa not only rebukes and rebels against the male establishment in her demeanour and appearance, she also takes on the (traditionally male) leadership role as protector and saviour of the subjugated women.

Ecofeminism, as seen through the lens of this film, is about the empowerment of women and the potential, far-reaching good that can come of it, but the ultimate resolution (the dethroning of Joe) is achieved only through an alliance with other (non-malevolent) male forces (including Max).

From this perspective, ecofeminism is not just about the gender-inflected challenges that the world faces, but also the opportunities for both sexes to collaborate on solutions to solve climate change, its causes and effects.

Outside of the West, the ecofeminist idea of women as the agents of change for a better, more environmentally sustainable world is something that is embraced in popular culture elsewhere.

For example, many of Japanese animation auteur Hayao Miyazaki’s famous works, such as Nausicaä of the Valley of Wind (1984), Princess Mononoke (1997), Spirited Away (2001), all centre on empowered female characters who have special relationships with aspects and forms of nature, and are called upon to salvage the earth from damage done by mankind.

What is also significant about these works is that their creators are men: the idea that women can and should be the focal point of our ongoing struggle to solve the problems associated with climate change is something that both genders can get behind.

And there is no better time to celebrate this than International Women’s Day.