“We have moved passed the point where we could debate the reality of climate change, we are now at the point where we need to ask how it will affect our daily lives, and what we can do about it.”

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

This was how Dr Cindy Bruyère, director for the Capacity Center for Climate and Weather Extremes, National Center for Atmospheric Research, Colorado opened the climate resilience breakfast hosted by The Purpose Business in Hong Kong.

Focusing on regional climate modelling, the Center has developed the Global Risk, Resilience, and Impacts Toolbox which interprets data like the impact of cyclone intensity that can be aligned with other data such as property development or transport for business operations.

Running real-time scenarios showing how cyclones or sea level rises could affect businesses left no one in the room in any doubt about the urgency with which businesses need to act beyond mitigation, that is, to pursue climate adaptation as an overall strategy.

Yet even companies with sophisticated sustainability strategies and multi-year environment, social, and governance (ESG) disclosures find it difficult to incorporate climate resilience into business strategies.

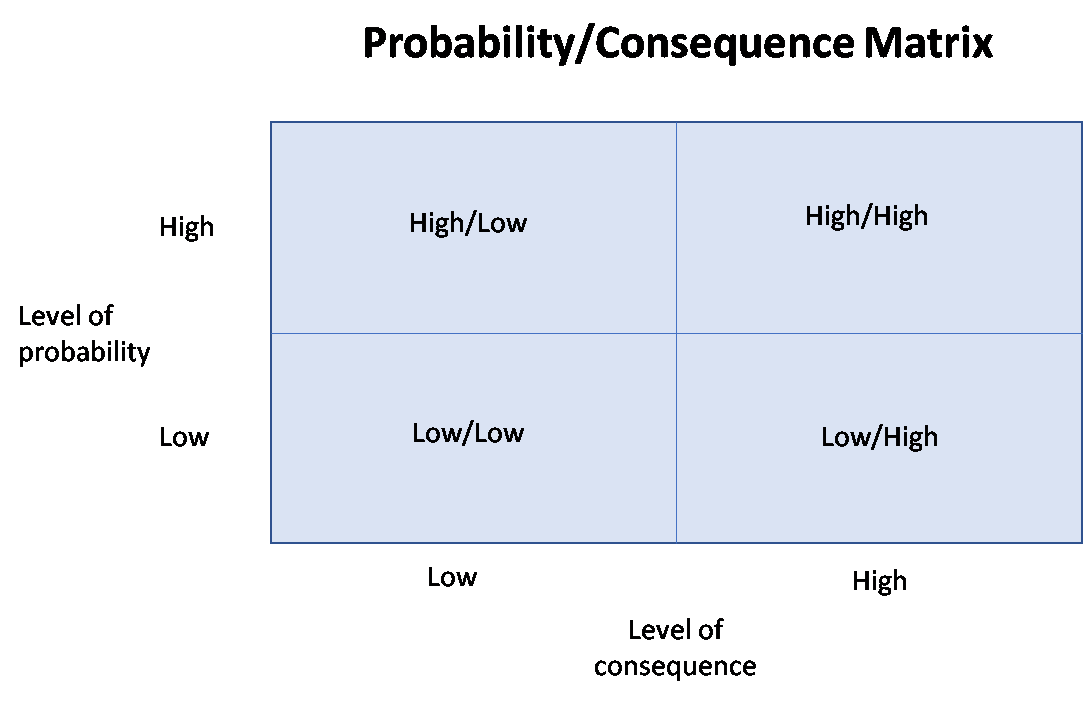

Responses range from “we don’t know how to do this—and we don’t have a starting point” to “we agree that disasters are climate change-related, but do they really have a high probability of occurring, and if so, how often and how bad are the impacts?” Often the excuse is that other critical priorities are ongoing and, besides, most companies are reluctant to be the pioneers for anything different.

One underlying sentiment is that understanding climate resilience exposes an organisation’s vulnerabilities—and that’s not easy to defend to shareholders. In presenting this to a board of directors or executive leadership, no one wants to deliver ‘bad’ news on another set of risk exposures. The task though is not to respond to a crisis. Rather, it is seeking preparedness for imminent yet uncertain crises.

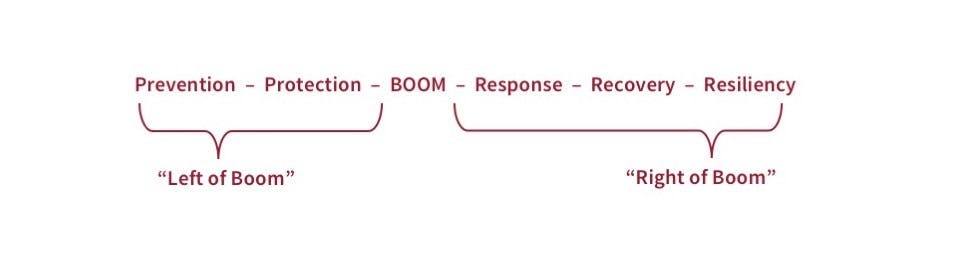

This is about resilience, says Juliette Kayyem, former assistant secretary at the US Department of Homeland Security. At its simplest, resilience is the ability to mitigate and withstand disturbances and bounce back afterwards, while continuing to function. Now a lecturer at the Harvard Kennedy School, Kayvem offers the ‘BOOM’ framework, BOOM being the point of when the crisis occurs.

This framework helps map vulnerabilities making the business case for climate resilience. If a property developer were to map investments and activities across the BOOM spectrum, most of the built-in hardware would be left of BOOM in “protection”, where green building and safety standards offer protection like double-glazed windows, fire exits and emergency response plans.

A transport company would have more in “prevention” (road safety, traffic dispersion, etc) as well as to the right of BOOM where systems “recovery” needs to be quick for airlines or mass transit operators.

Perhaps the missing phase is “preparedness” for the likelihood of disasters that may occur given specific business operations. There are two possible starting points.

First to systematically manage climate risks, we must secure relevant climate data. Companies that acknowledge climate risk need to invest in this process especially those with portfolios in multiple geographies facing various disaster types. Hotel groups that operate in island destinations or food companies invested in agriculture or manufacturing in low lying areas will find this useful as day-to-day operations depend on these data.

Second, use a probability vs consequence matrix. A hurricane sweeping the Atlantic would have been a low probability/low consequence phenomenon ten years ago but 2017 proved us wrong. In Southeast Asia, typhoon season timing has shifted so that severe weather events now span the year.

As high probability/high consequence events, managing for typhoon weather requires careful planning. Airlines need typhoon paths to plan for flight delays, fuel costs and compensation for passengers. Companies building infrastructure need to plan for re-work, improve sewage systems and work with public works agencies so that traffic, disruption and efficiency are all managed.

In short, it is prudent to consider scenarios other than those currently in the high probability/high consequence quadrant and prepare for them—fast.

In revealing vulnerabilities, companies will feel exposed, especially if it is unclear whether competitors have the same information.

“Common” industry vulnerabilities though exist in the public domain. Lack of supply chain transparency, brand-damaging labour abuses and poor environmental performance are vulnerabilities across entire industries. Regardless of big-name brands or start-ups wanting to position themselves as eco-alternatives, consumers will be sceptical if expectations of responsibility and ownership are unmet.

Climate resilience lies at the heart of our communities’ interaction with our environment. Best-selling author M Scott Peck said: “There can be no vulnerability without risk; there can be no community without vulnerability; there can be no peace, and ultimately no life, without community.”

To be a force for good, businesses should be ultimately working on what creates value both in the community and for our environment.

Pat Dwyer is the founder and director of Hong Kong-based sustainable business consultancy The Purpose Business.