Boracay Island, located in the Western Visayas region of the Philippines, has been the country’s top tourist draw since the 1980s when its fine powdery sand and clear blue water were first discovered by the world.

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

The island in Aklan province saw its tourism spike to a record high of 1.7 million visitors in 2016, followed by two million tourists in 2017, as it introduced new establishments such as a mall that housed the island’s first cinema.

The Malay Municipal Tourism Office said it was targeting 2.2 million visitor arrivals this year, but that was before trouble started brewing in paradise.

“

Once simple, the issues in Boracay were made complex by decades of apathy, short-sightedness and inaction.

Dr. Miguel D. Fortes, coastal ecologist, University of the Philippines

Last month, President Rodrigo Duterte highlighted the island’s long-running environmental woes and threatened to close the popular beach destination if these were not fixed in six months.

The feisty leader lashed at the hotels, restaurants and other businesses in the world-renowned island to clean up or he would ban tourism there.

“I will close Boracay. Boracay is a cesspool,” Duterte said in a speech during a business forum on February 9 in Davao City.

A fact-finding committee with the Senate and stakeholders was held recently to address the issue.

Dr. Miguel D. Fortes, coastal ecologist, biodiversity and integrated coastal area management specialist from the University of the Philippines, is one of the consultants for the project. He made a presentation in this meeting, where he cited the main issues facing Boracay: biodiversity loss, resource overexploitation, climate variability, habitat degradation, and declining water quality.

In an interview with Eco-Business, Fortes said these issues have persisted because programmes to solve the island’s problems have not addressed their root causes such as overcrowding, increasing pollution due to inadequate education and training, and the destruction of habitats due to weak law enforcement.

“Once simple, the issues in Boracay were made complex by decades of apathy, short-sightedness and inaction on the part of stakeholders,” he said.

As preparation for Boracay’s clean-up operation gets underway, local experts give their recommendations for how to get it back on its feet.

1. Regulate visitor numbers

Fortes cited overcrowding as one of the root causes of biodiversity loss and resource exploitation in Boracay.

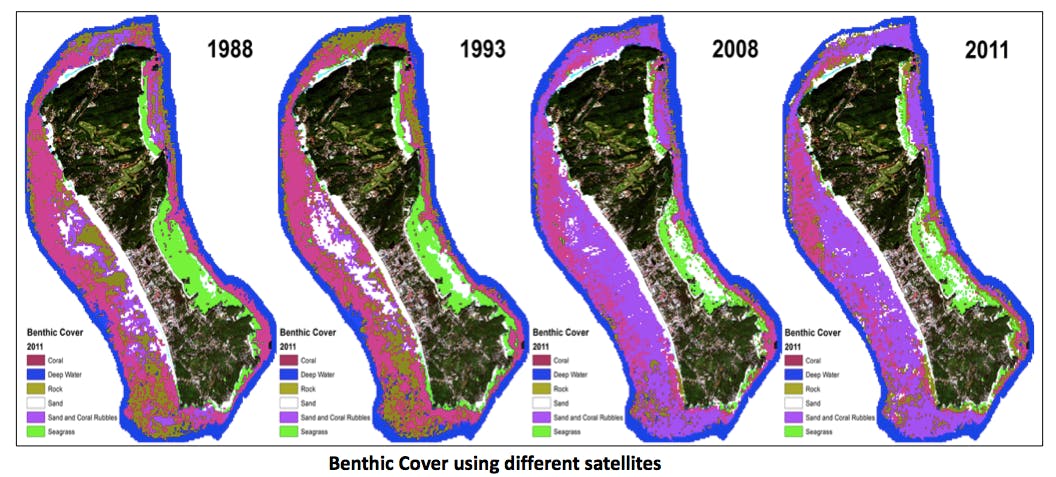

With a land area of just 1,032 hectares, Boracay has received more than a million visitors for the last two years. This weight in tourist numbers has meant an increase in unmonitored snorkeling and diving activities, which are blamed for damaging the island’s benthic cover, or the lower ocean floor where tiny organisms live and act as a source of food for bottom-feeding animals. Benthic organisms are good indicators of water quality.

Benthic cover, which is made of coral, seagrass, rock and sand, decreased by 70 per cent from 1998 to 2011, with the most significant decrease occurring between 2008 to 2011 when tourist arrivals increased by 38.4 per cent. There was also a dramatic increase in sand and coral rubble between 2003 and 2006, when tourism increased by 63.3 per cent.

Image: Dr. Miguel Fortes

2. Strengthen law enforcement to curb overbuilding

Habitat degradation and declining water quality are seen to be partly a result of weak law enforcement in Boracay, according to Fortes’ presentation.

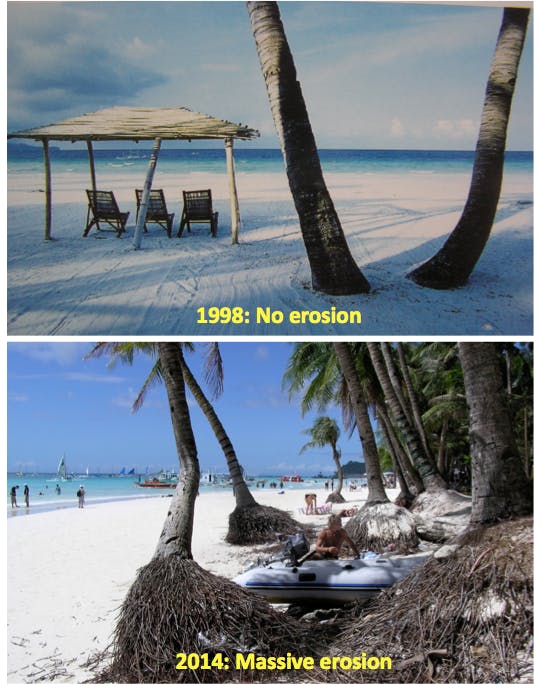

Due to the deterioration of the coral reefs there has been heavy erosion of White Beach, a four-kilometer stretch of pristine white sand which is considered the best part of the island.

Fortes said the erosion is caused by reduction of the reef’s two main functions: as a natural breakwater and as a supplier of beach sediment, all largely due to the improper construction of sea walls, restaurants and hotels on the backshore.

Boracay’s famous beach front “White Beach”. Image: Dr. Miguel Fortes

Water pollution has also worsened due to resorts and other commercial establishments that lack proper drainage systems that allow untreated waste water to flow directly into Boracay waters.

The dirty water results in “green tides” or algal blooms, now a common site in Boracay.

Algal bloom in Boracay. Image: Dr. Miguel Fortes

“How were these establishments able to get permits to build in the first place? The root cause is corruption or bribery. While the laws exist to limit building, those in authority with poor knowledge of the area issue permits without the proper building requisites,” Fortes said.

3. More education for policymakers and island residents

A lack of education and training among local policymakers is seen as another root cause for Boracay’s worsening water pollution.

Fortes cited a “lack of urgency among policy makers when addressing sustainable development issues,” such that they are not able to formulate and practice proper policies.

He recommended workshops for sustainable tourism in Boracay which would include creating a roadmap for environmentally-sustainable tourism in the central island.

He also pushed for collating scientific data, which would be useful for creating policies on coastal conservation. The database needed to be easily accessible and frequently updated—and also accessible for residents, he added.

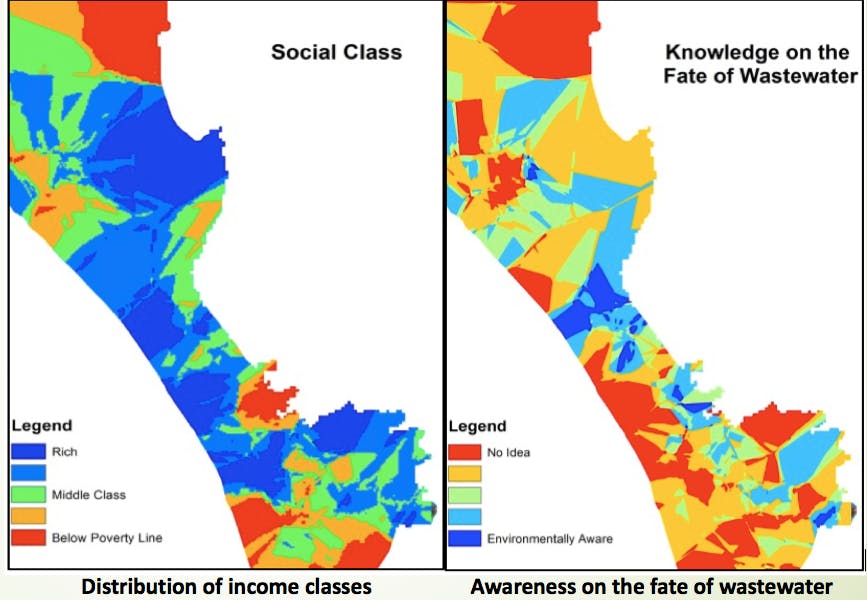

Awareness among households of the fate and effects of wastewater is worryingly low, Fortes showed in his presentation. Some 14 per cent of households do not have septic tanks, which means that wastewater from their homes flows directly into the environment, untreated.

“Most residents living in the western side of Barangay Balabag [where White Beach is located] have no idea of the fate and effects of wastewater discharged into public storm drains,” the ecologist said.

Image: Dr. Miguel Fortes

4. Switch to renewable energy

One of the identified root causes of Boracay’s issues is the high price of goods leading to an increase in demand for land, raw materials, food and energy.

Sarah Jane Ahmed, an energy expert for US-based think tank Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis (IEEFA), wrote a study in 2017 on how small islands in the Philippines can effectively replace outdated, polluting diesel fuel electricity-generation systems with solar and wind-powered grids.

A beach resort in Siquijor, Philippines makes use of solar panels which provide constant power, eliminating the need for outside sources for electricity. Image: Solenergy Systems, Inc.

In an interview with Eco-Business, she recommended the use of a renewable energy powered micro-grid with storage to reduce energy costs for Boracay.

“The financial and economic case for this is largely made on the high cost of imported diesel fuel and the need to improve the resilience of our islands from typhoons and the like,” Ahmed said.

“The Modernisation of small island power systems through the uptake of renewables and storage will supply cheaper, more efficient, secure, and cleaner power for Boracay.”

She noted how solar-powered electricity costs worldwide have fallen by 99 per cent since 1976 and 90 per cent since 2009.

“This stands to drive the eventual domination of renewables in the Philippines’ energy mix,” Ahmed said.

5. Protect indigenous people and the natural eco-heritage of the island

President Duterte has also been pressured to save Boracay’s social and cultural heritage, which is at risk of disappearing under the weight of tourism.

An online petition called on the president to empower the “Ati”—Aklan’s indigenous people and original residents of Boracay Island—to help protect the island.

Ironically, the Ati suffer from high unemployment levels in their native land, and face discrimination because of their dark skin.

The petition sought the government’s help “to give indigenous people the right to grow with their community in the island and participate in the local toursim industry.”

The Ati village in Boracay is being eyed by the Department of Tourism as an alternative tourist attraction on the island, to develop the cultural immersion experience for tourists.

Victoria Tauli-Corpuz, the UN special rapporteur on the rights of indigenous peoples, called the marginalisation of the Ati “scandalous” since they are the orginal settlers of the land.

“It is so scandalous that they are only given two hectares of land in Boracay, and they are not even allowed to cultivate and develop it. Their rights are totally violated,” Corpuz told Eco-Business in an interview.