The evidence is getting harder to dispute. Clean energy can provide 100 per cent of society’s electricity needs. Current renewable energy technology is reliable 24 hours a day, every day of the year, and industries’ insistence on using coal and other polluting sources for fear of intermittency—the inability of renewable energy to ensure an uninterrupted supply—no longer has a basis.

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

So why does Southeast Asia continue to be a global laggard in renewable energy deployment?

Rapid economic growth exceeding 4 per cent annually has seen the region double its energy consumption since 1995, and demand is expected to continue to grow by up to 4.7 per cent per year through to 2035.

Coal largely feeds this demand, accounting for up to 40 per cent of consumption. But coal’s impact on climate change and air quality have made the need for a transition to clean energy more pressing than ever.

Eco-Business asked the experts what Southeast Asian countries should do to accelerate the renewable energy transition, and this is what they say.

“

There is no place for coal subsidies in today’s energy markets.

Peter du Pont, clean energy advisor, Asia Centre, Stockholm Environment Institute

1. Scrap fossil fuel subsidies

For decades, Southeast Asian governments have helped the fossil fuels industry with generous subsidies.

But energy subsidies should be cut back or scrapped altogether—except in cases where they serve a specific public purpose, such as giving the poor easier access to energy, or short-term incentives to get new clean energy technologies into the marketplace, says Peter du Pont of the Stockholm Environment Institute’s Asia Centre.

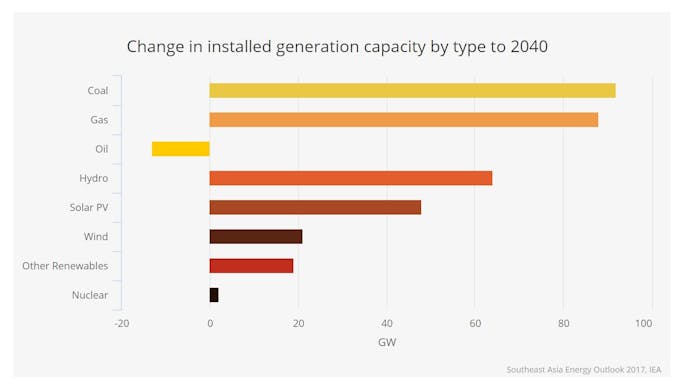

Renewables and high-efficiency coal, followed by gas, lead the charge for new power generation to 2040. A transition to more sustainable energy sources holds multiple benefits, says the International Energy Agency (IEA). Image: IEA

“There is no place for coal subsidies in today’s energy markets,” he says. “The cost of coal power in Asia does not include the significant negative health and environmental externalities caused by the combustion of this dirty energy source.”

Sara Jane Ahmed, energy finance analyst with the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis (IEEFA), adds: “Governments need to be efficient with their use of capital. Subsidies are not necessary in an industry where there are cheaper competing technologies,” she says, referring to the tumbling price of solar.

2. Swap feed-in-tariffs for auctions

Another energy policy which is in need of replacing is the feed-in-tariff (FiTs), which assure power players a fixed payment for energy production over long periods. While FiTs were responsible for the rapid growth in solar energy adoption in Germany where it was first trialled in the early 2000s, in countries like the Philippines, where energy policies may get scrapped with each change of administration, FiTs are proving discouraging to renewable energy investors.

Meanwhile, renewable energy auctions, where governments call competitive tenders to install a certain capacity of renewable energy-based electricity, have become prevalent in Europe, China, India, and Latin America in recent years.

Auctions, says Heymi Bahar, an energy analyst from the International Energy Agency (IEA), were the reason why India’s renewable energy investments topped those of fossil fuels last year. Investors were given confidence that they could recover their upfront costs over the long term, he says.

3. Open energy markets

One of the biggest obstacles to economic development is the cost of energy, and in many Southeast Asian countries, power costs are high because of base load, or the minimum level of demand on the grid which most coal-powered utility companies impose on consumers. Ultimately, consumers pay for energy they do not use.

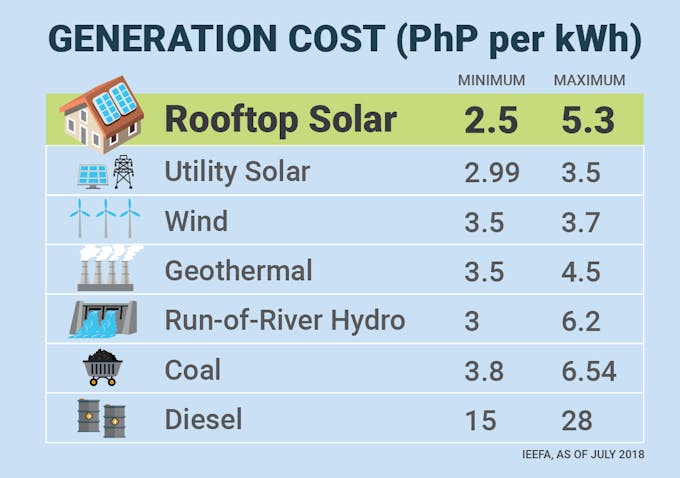

The cost per kilowatt-hour of electricity generation in the Philippines from renewable energy and fossil-fuel sources. Image: IEEFA

Ahmed says that to override the base load factor, countries must adopt “least cost thinking”, and find ways to produce energy at the lowest possible cost. “We should take advantage of the renewable energy technologies we have to reduce the actual cost per kilowatt-hour (kWh) of what we use,” she says.

IEEFA recently released a report that showed the Philippines can reduce electricity costs to just P2.50 per kWh and improve energy security by installing rooftop solar. The report showed that renewable energy has the ability to reduce overall systems costs, which will result in lower price electricity for the country.

Ensuring a range of different sources such as solar, wind, natural gas, hydropower, and geothermal in the energy mix will also boost the resilience of local energy supply. So if one source fails, other sources will pick up the slack, says Ahmed.

4. Make energy data more accessible and transparent

A transition to renewable energy depends on accurate energy demand data, Ahmed says.

Although increased rooftop solar in some countries has reduced demand for fossil fuels, it is seldom reflected in national energy demand projections. This causes governments to overestimate the energy capacity needed from coal, enabling them to continue to burn it, she says.

“This means if there is an oversupply we will be left with either stranded coal assets that will be paid for by the banks or consumers,” she warns.

“

If you want to fight climate change and do good for your country, improving energy efficiency is the cheapest way to do it.

Heymi Bahar, energy analyst, International Energy Agency

5. Prioritise energy efficiency

“If you want to fight climate change and do good for your country, improving energy efficiency is the cheapest way to do it,” Bahar says. He points out that governments only need to implement simple regulations to make certain appliances, such as energy-guzzling cooling systems, more efficient.

“The economics is very clear,” says Bahar. “Using LED lights, for example, is a no-brainer: You will get back your money very quickly because you save on electricity bills.”

6. Wake up to stranded assets

Coal investors in Southeast Asia may not yet see the climate risks of power sector financing, but they will soon wake up to the reality of stranded assets, says du Pont.

SEI Asia Centre is conducting a study to examine investor perceptions of climate-related risks in power sector financing in the region. “Our initial interviews reveal that the potential severity of the stranded asset problem in Southeast Asia is not yet a major part of the discussion in power sector investment circles,” du Pont says, citing a general lack of transparency on pricing and tariffs.

He argues, however, that commercial coal plants will be in decline in the next 20 to 25 years, and consumers will be locked into paying higher rates for coal-powered electricity as the price of renewable energy continues to fall.

7. Heed corporate climate action

While governments may be dragging their heels, climate-conscious companies are increasingly demanding clean energy in Southeast Asia. Firms like internet giant Google, which is planning to build a third data centre in Singapore and uses more energy in a year than the city of San Francisco, want to only use renewable energy to power their operations.

Google is one of the RE100, a group of some of the world’s most influential companies that have set a public goal to source 100 per cent of their global electricity needs from renewable sources by a specified year. The collective strength of these multinational brands—which includes just one Southeast Asian company, Singapore’s DBS Bank—will put pressure on governments to develop easier access to clean energy.

The future and the death of king coal

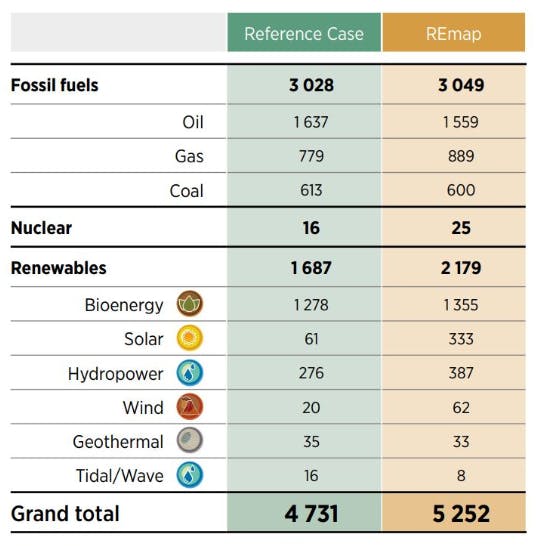

Employment in the energy sector by 2030 (thousand jobs). Image: IRENA

Energy experts agree that the energy transition will not be easy, with some job losses inevitable in the fossil fuel sector. But an inescapable fact is that the cost of renewables is declining, while the cost of coal-fired generation capacity remains constant.

“Southeast Asia and South Asia are the last markets for coal. If coal does not succeed in these markets, it’s dead,” Ahmed says.

The good news is that renewable energy has created thousands more jobs than fossil fuel-based energy. According to the International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA), the renewable energy sector worldwide employed 10.3 million people in 2017, more than offsetting fossil fuel job losses.

“Research has shown that clean energy resources such as energy efficiency and renewable energy are better at creating jobs than fossil-based power plants,” du Pont says.