Beijing is more than 4,200 kilometres (2,600 miles) north of the sandy beaches, oil palm plantations and tropical forests that distinguish peninsula Malaysia’s less prosperous South China Sea east coast from the rollicking economic growth on its western shore along the Strait of Malacca.

In November 2016, then-Prime Minister Najib Razak travelled to China’s capital to drum up investment in an audacious infrastructure development plan to balance the economic disparity between his country’s east and west coasts. He wanted China to finance and build a $14 billion trans-peninsular rail line, construct mammoth manufacturing plants, expand the port in the city of Kuantan, and encourage real-estate investment.

Conservation groups eyed the plan warily. They worried that one of the densest concentrations of new mega infrastructure projects in the world would produce runaway deforestation, erosion and pollution.

Following several days of ceremonies and negotiations, Najib left Beijing with an astonishing haul: China had agreed to spend $34.4 billion in Malaysia to finance and construct the big east coast infrastructure projects and 11 others across the country.

But what initially appeared to be a triumph of bilateral economic cooperation, albeit one with considerable environmental risk, was viewed by Najib’s opponents as a massive and threatening diplomatic overreach. Less than two years later, the consequences of Najib’s visit are visible in both countries.

A sweep of enormous construction projects is rising in this oceanfront district in Pahang state, and across Malaysia. And an outbreak of political disruption is occurring in Kuala Lumpur and Beijing. The two outcomes are a manifestation of the turmoil that so often occurs in planning and executing mega infrastructure in the 21st century. Project costs are exorbitant. Construction schedules are routinely violated. Civic opposition is often intense. Ambition can be overwhelmed by engineering lapses.

In Malaysia, corruption in 1Malaysia Development Berhad (1MDB), the national investment fund overseen by Najib, added another layer of uncertainty.

In May, Najib was ousted in a surprise election result by his former mentor turned opposition leader Mahathir Mohamed. Mahathir, returning for a second stint as prime minister, based his victory on withering criticism of the 1MDB corruption scandal and persistent nationalist concerns about China’s expanding sphere of influence in his country.

The change in administration altered China’s aggressive development plan for Malaysia, much of it connected to the 5-year-old Belt and Road Initiative, the most colossal economic development idea of the 21st century.

Determined to keep its economic engine running at maximum torque, China plans to spend three decades and trillions of dollars to build ports, airports, train lines, roads, power plants, transmission networks and online communications capacity for new international trade routes across 70 countries on three continents.

China regards Malaysia as a strategic base for its new Southeast Asia trade route from Beijing to Hong Kong, Kuala Lumpur, Singapore and Jakarta.

Weeks after the election, though, Mahathir suspended construction of the Chinese-financed trans-peninsular East Coast Rail Link project, saying its real cost was $20 billion, or $6 billion more than the price projected by his predecessor. He also curtailed two big Chinese energy pipelines, a high-speed rail line between Kuala Lumpur and Singapore, and put other China-financed projects under review.

During a visit to China this month to renegotiate some of the Chinese-financed projects, Mahathir and Chinese leader Xi Xinping agreed to indefinitely postpone the East Coast Rail Link and the pipelines. “Our priority is reducing our debt. For the moment, they are deferred until we can afford,” said Mahathir. “They are cancelled at the moment.”

The cancellations were another blow to the Belt and Road Initiative, which has encountered similar political and financial turbulence in Bangladesh, Indonesia, Nepal, Myanmar and Thailand.

In announcing the project suspensions in Malaysia, the new government has focused on finances and politics. But any slowdowns or cancellations could also benefit the environment. The suspensions are a break in activity and represent an opening for more public debate and review to reduce forest clearing and damage to streams and wildlife habitats.

“We’ve been worried about the rail project here,” said Noor Jehan Bt. Abu Bakar, a lawyer and chairwoman of the Kuantan branch of the Malaysian Nature Society. “It runs through protected forest. We don’t have a clear picture of how wide the corridor will be and how much forest will be cut.”

The start of Najib’s troubles

It was a journalist who broke up the infrastructure party between Najib and Xi Jinping, China’s president. On July 2, 2015, British journalist Clare Rewcastle Brown published an investigative article in her Sarawak Report blog that said Najib had diverted into his own bank account over $700 million from 1MDB, a figure later confirmed by the U.S. Federal Bureau of Investigation. The fund was also billions of dollars in arrears to its investors.

Rather than running from Najib, Xi marched straight to him. Chinese banks and developers, ripe with a vast investment treasury and ambition, sensed an opportunity to help Najib meet some of 1MDB’s financial obligations and gain easy entry to build projects in Malaysia. Some were viewed as good Chinese investments.

Most were needed for the new trade route.

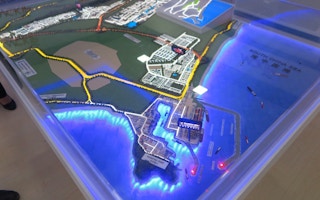

One is the $2 billion Melaka Gateway Port, a feature of a larger $10 billion mixed-use residential, retail, office, and entertainment project being built on reclaimed seabed on the west coast. Another is the planned $3.5 billion Robotic Future City, which is being constructed on 400 hectares (1,000 acres) of land reclaimed from the Strait of Johor.

China also wanted to invest in the $40 billion Bandar Malaysia mixed-use project planned for an unused military air base in Kuala Lumpur. The project faltered after Chinese investors dropped out last year and Prime Minister Mahathir cancelled the Kuala Lumpur-Singapore high-speed rail line, with its terminal in Bandar Malaysia.

Few regions, though, attracted China’s interest as intensely as the coast and scrub forest just outside Kuantan, a metropolitan district of 461,000 people, the capital of Pahang, peninsular Malaysia’s largest state. Outside the city lie ample state and private lands, available at competitive prices for new manufacturing bases to host the steel, chemical, palm oil, solar, electronics and gas-processing plants that China plans in Malaysia.

This story was published with permission from Mongabay.com. Read the full story.