Houseboats in Australia evoke images of relaxing river cruises and serene waters, but underneath them lies the murky business of dumping untreated wastewater from the boats into the rivers.

This was prevalent even as recent as seven years ago, when South Australia’s Environment Protection Authority (EPA) finally ruled that by 2011, houseboats must treat their greywater before discharging it.

This would have been a serious challenge if not for an invention called Aerofloat, launched by 66 year-old chemical engineer Ray Anderson and his children - from Sydney, Australia - which enabled houseboat owners to treat their effluent greywater efficiently and cheaply.

In a recent interview with Eco-Business, Anderson recalls that back in 2009, there were simply no suitable water treatment technologies for houseboats in Australia. Existing solutions were not light enough to keep the boats afloat, and used more energy than its off-grid power supply could support.

It was around that time that Anderson was approached by a property developer who planned to build a residential development which would include berths for houseboats along the state’s Murray River. The company asked Anderson, who has specialised in wastewater treatment since the 1970s, to help find a suitable solution.

Together with son Michael, an industrial design specialist and daughter Katie, an engineer, Anderson set his sights on adapting a common water treatment method known as dissolved air floatation (DAF), and modify it for use on houseboats.

He arrived at this method after realising that the alternative method of treating water - a cumbersome biological treatment method which uses microbes to digest bacteria - could be replicated using DAF technology, a simpler technique.

Small scale, big impact

In DAF systems a chemical coagulant is mixed with the wastewater which causes the pollutants to bind together. Air is added to a portion of the treated water under pressure and then it is quickly decompressed, forming millions of microscopic air bubbles. The effect is similar to opening a can of soda.

These air bubbles are mixed with the wastewater containing the coagulated pollutants and floats them to the surface. Mechanical scrapers then remove the floated pollutants from the top of the water.

The scrapers are not only complex moving parts which cost more to install and maintain, additional energy is also required to operate them.

.jpg?auto=format&dpr=2&fit=max&ixlib=django-1.2.0&q=45&w=340)

L-R: Katie Moor, Ray Anderson, Australian Treasurer Scott Morrison, Michael Anderson. Image: Aerofloat

But with Aerofloat, the Anderson family have created a system that significantly cuts the energy needed and reduces the cost by about half. In their solution, wastewater is collected in a small, enclosed tank, fitted with a funnel at the top.

Once the chemical coagulant has been added and compressed air is released into the tank, the water level in the tank is simply increased till the foam is pushed out of the funnel and removed, eliminating the need for scrapers.

This design, which is patented by the company in several countries including India and the United States, makes for a DAF treatment system that is more affordable, compact, and sustainable, says Anderson, who financed the initial development of prototypes with AUD$150,000 of his own money.

For one thing, its small size and the lack of moving parts means that lightweight plastic is a suitable construction material, as opposed to the steel or concrete used in traditional tanks.

This is a key differentiator which allows the units to be installed on houseboats, and clean up grey water that would otherwise be discharged untreated.

Aerofloat also uses much less energy than conventional DAF systems because it increases the water level in the holding tank to remove the scum off the surface instead of relying on scrapers – while this is a must-have feature on houseboats, it also appeals to other industries wanting to cut their energy bills.

Following a few successful trials, the Sydney-headquartered Aerofloat received grants worth AUD$50,000 from the EPA and federal government to get its technology certified as effective, and to commercialise it.

Since it began mass producing the systems out of a small factory in South Australia in 2010, the company has installed more than 120 units on houseboats across the continent.

Aerofloat has also caught the eye of other industries with greywater treatment needs, such as the food and beverage and mining sectors, among others.

Katie Moor, Anderson’s daughter and Aerofloat’s marketing and systems manager, tells Eco-Business that the company had always intended to develop the same technology for larger scale facilities.

In 2011, Aerofloat began building a system which could process 100 litres of water a minute - about seven times the processing volume of a houseboat model. It did this with the help of the Australian government’s industry development agency, which financed half of the AUD$800,000 project.

By mid-2012, the company had installed its first industry-scale unit at the premises of food firm Sunfresh Salads in Adelaide, Australia.

An Aerofloat installation at Sunfresh Salads, an Australian fresh food company. Image: Aerofloat

Today, other Australian companies such as chicken farms, cheese factories, and a vegetable oil manufacturing plant also use Aerofloat’s technology, which help them avoid costly sewage treatment fees and complicated grease traps, says Moor. A total of 20 industrial treatment units have been sold to date, she adds.

On the back of the increased popularity of Aerofloat, the company went on to develop a unit that can treat 200 litres of wastewater per minute, it also designed a modular system where four 200-litre units can be linked up and used simultaneously.

Another AUD$250,000 grant from the Australian government, awarded this September, helped Aerofloat commercialise the modular technology, and the family, which has taken on three more staff members since its founding, has plans to install the first system at a plastic recycling plant in New South Wales early next year.

The technology will also help this facility, located in an arid part of Australia, reuse its wastewater and reduce overall water use, says Moor. The units sell for about AUD$9,000 for houseboat models, while the 800 litre/minute modular systems cost around AUD$70,000. Installation charges are separate.

From trial and error to precision design

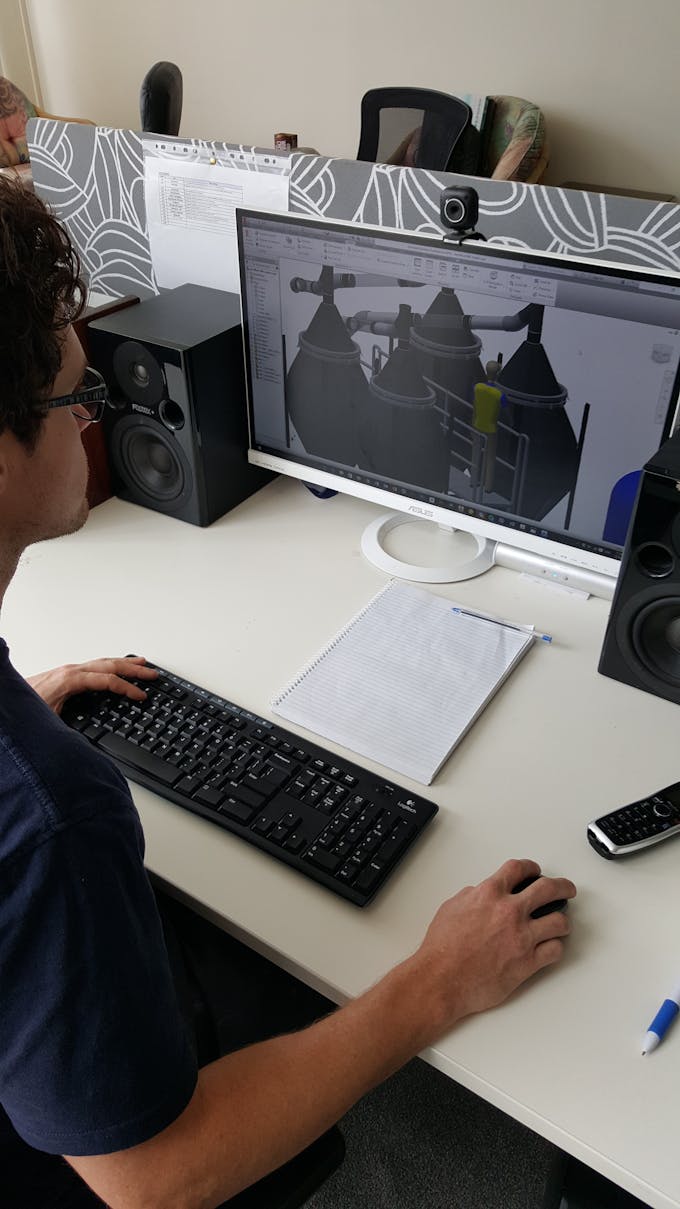

Michael Anderson, operations manager, Aerofloat, designs new systems using Autodesk Inventor. Image: Aerofloat.

Apart from manufacturing the units in its facility in Mannum, South Australia, Aerofloat also handles the design of these water treatment systems and manages their installation.

While the initial Aerofloat models were designed using little more than engineering expertise and basic trial and error, Moor shares that the firm’s rapid growth would not have been possible without 3D digital prototyping software.

“As we ventured into treatment system design and project management, we realised we needed software to plan layouts and help clients visualise the benefits,” she says.

Her brother Michael, who oversees Aerofloat’s operations, was familiar with Autodesk, a global leader in 3D design, engineering and entertainment software, when in university.

In the hope of gaining access to Autodesk software, the company applied for Autodesk’s Entrepreneur Impact Program last year.

This is an initiative to support early-stage start-ups and entrepreneurs in the social, cleantech, and environmental sectors. Eligible companies receive Autodesk software worth up to US$150,000 to design, visualise, and simulate their ideas and accelerate their time to market through 3D digital prototyping.

Aerofloat was selected for the programme in May, and now uses Autodesk’s Inventor tool to model all its treatment plants, and mock-up conceptual layouts for clients.

Another 3D modelling software, AutoCAD, helps Aerofloat create diagrams of how various components in the system - storage tanks, valves, pipes, and more - will fit together.

This ability has helped the company win over more clients, says Moor.

“The 3D modelling software gives a very complete picture of what the system will look like, so we can show clients exactly what they will be getting and alleviate any concerns they may have,” she explains.

For example, as space is often limited, clients worry whether the Aerofloat system will fit into cramped quarters. Mapping the exact location and position of the system virtually assures clients that the solution will be suitable.

A screencap of 3D modelling of an Autodesk system in Inventor. Image: Autodesk

The software also allows the company to see how its own technology will fit in with external structures like tanks or even biological water treatment systems, notes Moor. “It makes the detailed design more efficient, and realistic,” she says.

For example, Aerofloat has distributors in New Zealand. Sending them Autodesk drawings along with the equipment allows them to see exactly how components fit together. This not only helps with sales, but also ensures that distributors avoid mistakes in the assembly and installation process.

New frontiers

As demand for Aerofloat’s technology grows, the company has plans for bigger installations and newer products.

Anderson adds that the family is also eyeing overseas markets, especially Asia.

The family has installed a Aerofloat system at a factory which manufactures speaker components in Malaysia last year, and in November 2015 the company participated in a trade show to Vietnam.

It is also exploring opportunities in the Philippines, and the Middle East.

“These regions have major water security challenges, and struggle with industrial water pollution,” says Anderson. “Aerofloat can address both these challenges simultaneously with our affordable, effective technology”.

Aerofloat is part of the Autodesk Entrepreneur Impact Program. The program supports early-stage start-ups and entrepreneurs in the social, cleantech, and environmental sectors. As part of the program, eligible companies receive world-class software to design, visualise, and simulate their ideas and accelerate their time to market through 3D Digital Prototyping. To apply for or learn more, visit www.autodesk.com/entrepreneurimpact and follow @AutodeskImpact.