Singapore is trapped in a vicious circle caused by urbanisation, exacerbated by climate change and locked in by a national obsession with keeping cool. The city is getting hotter. As it gets hotter, the air-conditioning is cranked up. The more air-conditioning that is blasted out, the hotter it gets.

The outside air in Singapore’s built-up areas, where buildings belch aircon exhaust day and night, is up to 7 degrees Celsius hotter than in the tropical island’s shrinking green areas, observes Professor Lee Poh Seng, deputy director of the Centre for Energy Research & Technology at the National University of Singapore (NUS).

Lee is founding a consortium of government, industry and academic thinkers called CoolestSG—short for Cooling Energy Science and Technology Singapore—to find new ways to tackle a cooling conundrum that is particularly acute in the tropical metropolis.

The amount of energy used to cool Singapore—which has more installed air-conditioning units per capita than anywhere in Southeast Asia—is projected to grow by 73 per cent between 2010 and 2030, according to Lee’s figures, as the built environment mushrooms to house a population projected to grow from 5 million in 2010 to just under 7 million over the next 12 years.

Singapore’s late former prime minister Lee Kuan Yew famously called air-conditioning the greatest invention of the 20th century, but as Minister for National Development Lawrence Wong pointed out in a speech at the International Green Buildings Conference (IGBC) in September, air-conditioning is energy intensive and relies on century-old technology.

Cooling systems consume 40 to 50 per cent of a building’s energy, and produce large quantities of the greenhouse gases that drive climate change. If Singapore stands a chance of hitting its Paris Agreement target for cutting carbon intensity by 36 per cent of 2005 levels by 2030, it is going to have to get to grips with its addiction to air-con.

Finding better ways to chill

At IGBC, Singapore’s Building and Construction Authority (BCA) announced that by 2030, it wants the city’s thousands of high-rise buildings to be “super low energy”; 60-80 per cent more energy efficient than they were in 2005, with smart air-conditioning among the proposed methods for reducing energy consumption.

Among the island’s most energy-guzzling buildings are computer data centres. Facebook is planning to build a US$1 billion, 11-storey data centre on the island, while Google has a third facility in the pipeline. Singapore Info-communications Media Development Authority (IMDA) wants data centres to be run more efficiently and at higher temperatures to reduce cooling demand.

“

There’s a disconnect between what researchers know about new cooling systems, and what building owners actually need.

Professor Lee Poh Seng, deputy director, Centre for Energy Research & Technology, National University of Singapore

The problem with finding the solutions Singapore needs to tackle its cooling challenge is a gap between research and industry—and CoolestSG is being set up to bridge it, explains Lee.

“Researchers show how wonderful technology is in the lab without assurances that it’ll perform well in a building. There’s a disconnect between what researchers know about new cooling systems, and what building owners actually need,” he says.

Installing more efficient cooling systems is the best place to start, he says—the more efficient the system, the less waste heat, easing the urban heat island effect and lowering Singapore’s contribution to climate change.

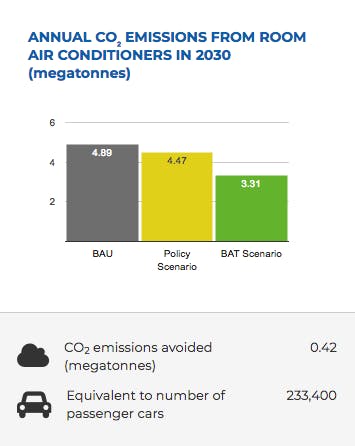

Singapore’s annual emissions from AC by 2030. BAU = busienss as usual; policy scenario = minimum energy performance standards ; BAT = best available technology. Source: United4efficiency.org

If Singapore switched to the best available cooling technology, it could cut energy consumption by 30 per cent—and by 2030 emissions would be cut equivalent to taking 233,400 cars off the road and energy costs saved equivalent to building eight 20-megawatt power plants, according to data from the United Nations’ United for Efficiency project.

Ideas to trim Singapore’s cooling budget include replacing data centre air chillers with liquid cooling systems, which are a far more efficient way to prevent data centres from overheating.

Traditional home air-con units could be replaced with breakthrough chillers developed by NUS that use water instead of harmful refrigerants, use 40 per cent less electricity to operate, and are cheaper to manufacture.

Dehumidifier membranes could dry the air rather than chill it—it is high humidity that makes Singapore’s climate feel uncomfortable, not the heat. But Lee points out that dehumidifier membranes use a lot of energy to suck air through them, and the systems are too big to use in residential buildings.

Membranes and district cooling systems—which save energy by pumping chilled water from a centralised plant to multiple buildings—are good examples of how CoolestSG could bring academia and industry closer together to work out how new technology can be adopted in practice, and how research can be guided on what the industry really needs, says Lee.

While Singapore’s cooling problem is big, so are the potential business opportunities from solving it, Lee says. Singapore could become a regional hub for cooling technology, and her neighbours—which face similar cooling challenges but on a larger scale—will “naturally look to us for solutions,” says Lee, who hopes CoolestSG can become a global platform for other countries to use and trade ideas.

Cool by design

The most cost-effective way for Singapore to hit its energy targets is to design buildings that don’t need to be cooled much in the first place. But that will require a mindset shift among building owners and occupants, Lee says.

Public buildings are kept about 40 per cent cooler than they need to be, because building owners tend to plan for the hottest days and don’t power the air-con down when it’s not needed, it was noted in Eco-Business’ study Freezing in the tropics: Asean’s air-con conundrum in January. No wonder Singaporeans complain more about being too cold indoors more than their Southeast Asian neighbours, the study found.

But while in less affluent Southeast Asian countries a chilled building is something of a luxury, in Singapore air-con is expected. “Passive design is a good way for buildings to keep cool without air-con. But society needs to accept it,” Lee says. “My son can’t seem to survive without air-con.”