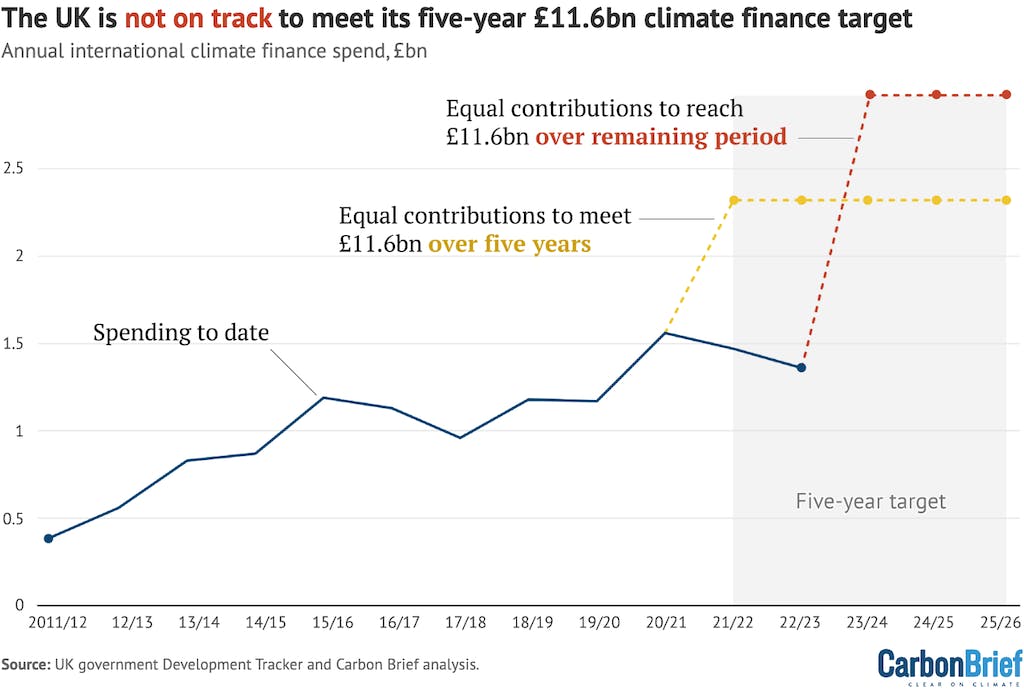

A freedom-of-information (FOI) request reveals that, rather than rising steadily to meet a target of £11.6bn over five years, UK climate spending overseas has fallen for two years in a row.

It is now around £2bn off track – assuming there should have been even progress towards the goal.

Boris Johnson’s government, with current prime minister Rishi Sunak as chancellor, committed in 2019 to ramping up its international climate finance (ICF) in order to reach a target of £11.6bn between the financial years 2021/22 and 2025/26.

The figures obtained by Carbon Brief show that UK spending has dipped from £1.56bn in 2020/21 to £1.47bn in 2021/22 – and around £1.36bn in 2022/23.

The numbers for 2022/23 are described in the FOI release as “provisional”, but the total sum is similar to one recently reported by the Guardian, based on leaked civil service documents.

Carbon Brief understands that the government’s figures for that period could be revised upwards when the final numbers are released, but are still likely to fall short of the £11.6bn trajectory.

The government would now have to roughly double its recent annual spending over the next three years, on average, if it is to stand any chance of delivering its pledge.

The UK is facing mounting pressure to provide more money to help vulnerable nations deal with climate change. Yet the government has slashed its overall budget for foreign aid, citing economic pressures at home. It has also redirected some of its foreign-aid spending towards the domestic processing of asylum-seekers.

Climate-finance experts tell Carbon Brief that the current shortfall is “troubling”, adding that it will now be “highly challenging” for the UK to achieve its goals without strong political will.

£11.6bn pledge

Former prime minister Boris Johnson announced in 2019 that the UK would spend £11.6bn on ICF between the financial years 2021/22 and 2025/26.

This has since been reinforced by his successor, Rishi Sunak, who told leaders at the COP27 climate summit in 2022 that he “profoundly believe[s] it is the right thing to do”.

“

Engagements of the current government also show that the commitment to the climate agenda is not as strong as one might have hoped. So I would be surprised to see the spending doubled.

Faten Aggad, adjunct professor, University of Cape Town

The target doubled the government’s previous five-year pledge to spend “at least £5.8bn” on tackling climate change between 2016/17 and 2020/21 – a goal that has been achieved.

Both targets make up the UK’s contribution to a wider promise by all developed countries, as part of the Paris Agreement, to ramp up climate finance for developing countries to US$100bn a year by 2020. Three years on, these nations are still yet to reach this target.

Without significantly increased climate finance, developing nations say they will not be able to transition to low-carbon economies and protect their people from climate hazards.

The UK’s climate finance spending has been under intense scrutiny in recent years.

First, the government slashed its overall development aid spending from the UN-backed benchmark of 0.7 per cent to 0.5 per cent of gross national income (GNI), citing the economic shock of Covid-19. Climate projects are among the many under threat from cuts.

Since then, the expansion of military aid to Ukraine and diversion of foreign aid to support refugees arriving in the UK have sucked up more of the shrinking resource pool.

In July, the Guardian reported on a leaked civil service briefing for ministers, explaining why the combination of these factors would justify dropping the £11.6bn goal altogether. The government has denied that it intends to drop the pledge.

Responding to a written question on 17 July, development minister Andrew Mitchell confirmed that the UK had spent “over £1.4bn” on ICF in 2021/22. However, he did not share data for 2022/23 or plans for spending out to 2025/26.

FOI requests

Carbon Brief submitted FOI requests to the three government departments responsible for running climate-related development projects: the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO); the Department for Environment Food and Rural Affairs (Defra); and the now-defunct Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (BEIS).

They provided data on ICF spending between 2011/12 and 2022/23, although Defra withheld its 2022/23 data, stating it was “yet to finalise” it. Both the other departments provided this data, with the caveat that the figures were “provisional”.

(For in-depth analysis of more than a decade of climate finance spending, see Carbon Brief’s full analysis.)

The annual totals, broken down by financial year, can be seen in the chart below. (Spending by Defra, which makes up roughly 3 per cent of total climate finance, has been estimated for 2022/23 based on the average spend over the previous five years.)

Annual ICF spending has more than tripled since the UK started officially providing it in 2011. However, as the data obtained by Carbon Brief shows, for the past two years it has been in decline, pushing the £11.6bn goal further out of reach.

Annual ICF, £bn, by financial year for the period 2011/12 to 2022/23, indicated by the blue line. Red dotted lines indicate the annual average spend that would be required to meet the government’s five-year £11.6bn goal by 2025/26, both from a starting point of 2020/21 (yellow) and a starting point of 2022/23 (red). Data for 2022/23 is “provisional”. Data from Defra for 2022/23 is based on the average amount provided in the previous five years, as this department declined Carbon Brief’s FOI request for this year. Source: UK government data obtained by FOI request.

If the £11.6bn target had been split evenly over the five years covered by the pledge, the UK would have spent £2.32bn annually on climate finance between 2021/22 and 2025/26.

So far, however, the government has fallen far short of this, spending £1.46bn in 2021/22 and just £1.36bn in 2022/23. This amounts to a £1.81bn – or 39 per cent – shortfall over the two-year period, relative to even progress towards the £11.6bn goal.

If the government is still to meet its £11.6bn target, climate finance would have to more than double to £2.92bn in 2023/24 and stay that high until 2025/26 – an unprecedented increase.

The 2022/23 figure obtained by Carbon Brief aligns with the Guardian’s reporting on a leaked civil service document, which “confirmed” that ICF spend for 2022/23 was £1.35bn – and expected to rise to around £1.59bn in 2023/24.

Despite this confirmation, Carbon Brief understands that, when the final spending total for 2022/23 is released, it could be higher.

Jonathan Beynon, a senior policy associate at the Center for Global Development who, until 2022, worked for FCDO on climate finance and other issues, tells Carbon Brief this could be achieved in part by reclassifying more funds within existing foreign aid projects as climate-related. Again, this was mentioned in the leaked document.

A government spokesperson tells Carbon Brief that “the government remains committed to spending £11.6bn on international climate finance and we are delivering on that pledge”, adding that “we will publish the latest annual figures in due course”.

‘Shockingly low’

All of this means that the £11.6bn target is slipping out of reach, according to former Conservative FCDO minister Zac Goldsmith, who resigned from government in June, citing its “apathy” towards climate change and the environment. He tells Carbon Brief:

“Technically, [the target] does remain government policy, but the shockingly low levels of expenditure make it a mathematical impossibility that the promise can be kept. Among beleaguered and hard-working civil servants this is an open secret and well understood. Indeed, the only way the promise can be kept is if the next government in its first year spends well over 80 per cent of all its bilateral spending on climate, which clearly cannot happen with all the other important commitments we have.”

Clare Shakya, a climate finance expert at the International Institute for Environment and Development (IIED), tells Carbon Brief it would be “highly challenging” for the government to “double the level of spending in a year and still ensure the projects and programmes it was supporting were of good quality”.

Faten Aggad, a climate diplomacy expert and adjunct professor at the University of Cape Town, agrees that it is “doubtful” the UK government would prioritise climate spending with its current economic outlook and a general election looming. She tells Carbon Brief:

“Engagements of the current government also show that the commitment to the climate agenda is not as strong as one might have hoped. So I would be surprised to see the spending doubled.”

However, Beynon tells Carbon Brief a “backloaded trajectory” – where spending started off relatively low and then increased more towards the end – was always envisaged for the five-year £11.6bn target period. (This is confirmed in the Guardian’s reporting, which says the government’s internal target for ICF spending in 2022/23 had been £1.77bn.)

He notes that the same pattern can be seen in the previous five-year target period, which still resulted in the goal being successfully met. A slow start can reflect the time taken for new climate projects to be set up and developed.

That said, Beynon adds that he would have expected an “uplift” by 2022/23, so the trend continuing downwards would be “troubling”. As for whether the target can still be achieved, he says:

“The short answer is: it’s possible, but it’s challenging…Primarily because of the wider context – the cuts in ODA [official development assistance] and the decision to choose to spend a good chunk of that ODA on hosting refugees.”

While developed countries are technically allowed to spend some of their aid budget on housing refugees, the UK spent an unusually high amount – around 30 per cent – on this in 2022, to accommodate people arriving from Ukraine and Afghanistan. Only three nations, none of them major aid providers, spent higher proportions of their development aid in this way.

Experts tell Carbon Brief that, depending on the government in charge and how much they prioritise international development, the target could still be achieved.

“The goal is certainly within reach if the political will is there to achieve it,” Saleemul Huq, director of the International Centre for Climate Change and Development (ICCCAD) in Bangladesh, tells Carbon Brief.

The Treasury has confirmed that foreign-aid spending will likely not be restored to 0.7 per cent of GNI until at least beyond 2027/28, if the Conservative government remains in power – two years after the £11.6bn deadline. The opposition Labour party has said it will examine a “pathway back to 0.7 per cent” over the course of the next parliament, if it wins the upcoming general election.

Beynon says that, with such widely publicised targets in place, climate-related development spending has, in his view, been “relatively protected”, compared to other areas of development aid that have felt the impact of cuts.

At the recent G20 summit in India, Sunak announced a pledge of £1.62bn in climate finance to the Green Climate Fund (GCF), described by the government as a “major contribution” towards its £11.6bn commitment.

Yet given the wider state of UK climate finance, Goldsmith says the prime minister, or chancellor Jeremy Hunt, would need to “personally intervene” to bring the UK back on track for the goal. Goldsmith criticises Sunak for “pretending we are on course when [he knows] we simply are not”.

Experts warn that a failure to scale up climate finance would seriously threaten the UK’s international reputation. Shakya says:

“If the UK does not meet its own promised contributions, this will not only impact the UK’s standing, but also whether any rich countries can be trusted.”

In less than two months, Sunak will travel to COP28 in Dubai where there will once again be significant pressure placed on developed countries to meet their existing climate-finance pledges – as well as raise the bar higher in the coming years.