Sustainability claims made by the Singapore Formula One Grand Prix (SGP) have been questioned for overlooking the huge carbon cost of the race, which gets underway this weekend (30 September to 2 October 2022).

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

SGP has been promoting its efforts to reduce its environmental impact in line with F1’s ambition to achieve net-zero emissions by 2030, a target set in 2019 to appeal to younger fans and woo green-minded sponsors.

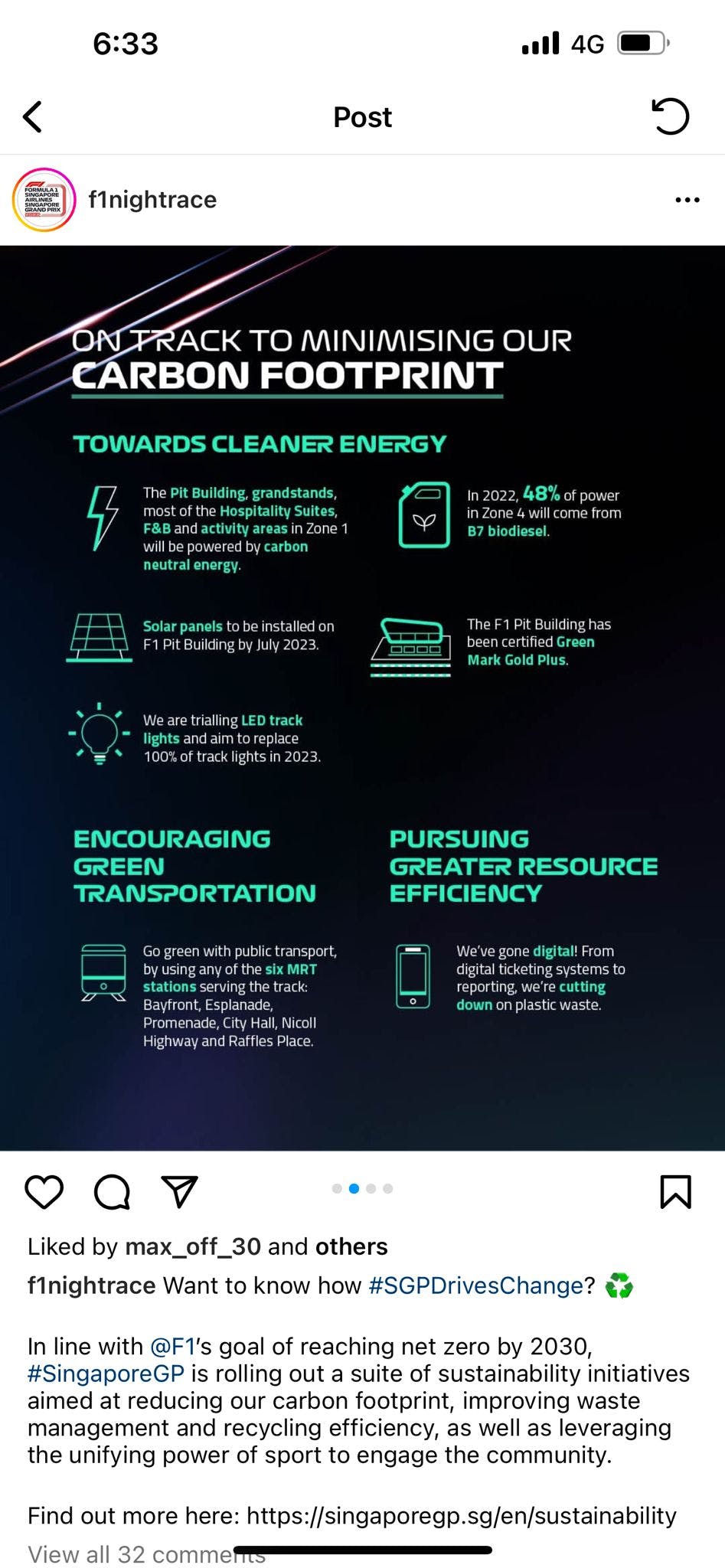

In social media posts, SGP claims that it is “on track to minimising our carbon footprint” by digitising tickets, trialling LED track lights and using carbon neutral energy to power the event venue, but provided no information on the actual carbon footprint of the event.

By next year, SGP said solar panels will be installed on the pit building, which has been certified sustainable by Singapore’s green building rating system.

The event organisers also said they are “encouraging green transportation” by informing punters which subway stations are nearest to the venue.

“

Our commitment is to become one of the most environmentally sustainable street circuits on the F1 calendar

Singapore Formula One Grand Prix spokesperson

Singapore Formula One Grand Prix’s Instagram post on the event’s carbon reduction measures. Image: Instagram

Other measures SGP is taking include ending the sale of water in single-use plastic bottles, switching to disposable beverage cartons and introducing more refill stations.

It is also trialling biodigestors, recycling cooking oil, and using more segregated recycling bins and sustainably-sourced tableware.

A post about the SGP’s sustainability efforts using the hashtag #SGPDrivesChange posted on Instagram received a mixed response.

One poster pointed out that the emissions from logistics far outweighed event operations, and the sport’s plans to increase the number of races in a season from 22 to 24 next year would negate any measures to reduce the carbon footprint of the Singapore race.

Another poster wrote: “hypocrites.”

A few fans meanwhile complained that they would no longer receive plastic tickets as memorabilia.

Ho Xiang Tian, co-founder of environmental group LepakInSG, noted the event’s green credentials were being promoted without acknowledgement of the wider climate impact of the race, which he said was greenwashing.

According to a 2019 audit of F1’s emissions, the sport emits the equivalent of 30,000 homes in a year, or 256,000 tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent.

Ho said the promoted sustainability measures focus only on the event operations, which constitute 7.3 per cent of the race’s overall carbon footprint; “so not really significant in the larger scheme of things.”

Far larger are F1’s emissions from logistics (45 per cent of the total), business travel (27 per cent) and production processes and team factories (19 per cent).

“More than 70 per cent of their carbon emissions come from flying crew and equipment around the world – not including their fans who jet in to watch the races. This is not mentioned on their website when they are talking about sustainability,” he said.

A spokesperson from Singapore Climate Rally, the non-profit behind Singapore’s first climate protest, said if SGP was serious about reducing its carbon footprint, it should be transparent about the total carbon emissions caused by a single F1 event and show how much of a reduction these measures amount to, as a percentage of the total.

The Singapore Grand Prix is the only night race on the F1 circuit, so the emissions from flood-lighting the event are likely to be particularly high.

Counting the carbon cost

SGP told Eco-Business that 2022 is the first time the carbon footprint of the event will be measured, using the GHG Protocol, a framework for measuring emissions. It plans to measure its emissions from mobile power generators, electricity, gas, water, waste and local transport.

SGP said it recognised that events are resource-intensive, and has taken a “measured and gradual” approach to sustainability “to ensure that we can continue delivering a world-class sporting event that is safe and smooth for all involved.”

The event organiser said disposables had not been removed from the event entirely, and water would be available in beverage cartons rather than plastic water bottles, and at refill stations. SGP did not explain the difference in the carbon footprint of plastic bottles and beverage cartons.

“It remains important to make the purchase of still water available to our patrons, especially in the Singapore heat,” SGP said.

Formula 1 has rolled out a range of measures to reduce its environmental footprint globally since 2019.

According to F1, switching to remote operations has almost halved the number of people the sport flies around the world to stage the races, and reduced travelling freight by 34 per cent.

The sport has also banned single-use plastic for staff at events, is switching to lower-carbon biofuels for the racing cars – there are no plans to abandon internal combustion engine vehicles – and plans to power its facilities and factories by renewable energy.

However, Ho said that F1 needs to rethink its model if it is serious about reducing its carbon footprint, rather than continue “with the same model but greener.”

He proposed holding the races in fewer regions, or using one circuit that is reconfigurable, to slash the transport and logistics emissions that make up the biggest chunk of the sport’s carbon footprint.

Singapore welcomes the Formula 1 party a month after the government held a public consultation to debate whether to set more a ambitious climate target in line with the Paris Agreement on climate change.