Financial institutions propping up agribusinesses with poor social policies will come under the spotlight as investors take greater care to ensure value chains comply with more stringent environmental, social and governance (ESG) requirements. Banks run the risk of loan defaults and stranded assets due to the impacts of climate change and harmful social practices that will ultimately undermine the profitability of agribusiness, according to a new report by Fair Finance Asia (FFA) in collaboration with the Gender Transformative and Responsible Agribusiness Investments in Southeast Asia (GRAISEA).

The study, Harvesting Inequality, conducted by FFA-GRAISEA assessed banks in Cambodia, India, Indonesia, Japan, Laos, Malaysia, Pakistan, Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, and Vietnam. It found that social issues are very poorly integrated into the sustainability policies of Asian banks. The report said the scores of the policy assessment (of the publicly disclosed policies of the banks) equate to a “significant gap” between what is expected from banks in international and regional sustainability standards and the banks’ public sustainability policies and management framework.

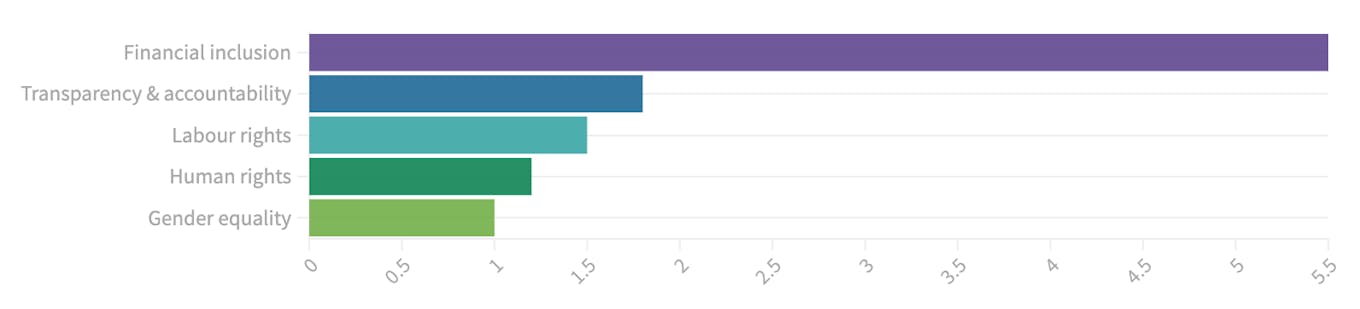

Fair Finance Asia’s (FFA) new study assessed the policies of 54 Asian financial institutions actively providing credit and underwriting services to agriculture companies. The results highlight weak enforcement or overall lack of policies on gender equality, human rights, labor rights, and transparency and accountability. Source: Harvesting Inequality, FFA & GRAISEA.

Agriculture remains a major employer in many developing economies in Asia. Eight out of 10 countries in ASEAN depend on agriculture and its production with about 350 million smallholder farmers producing most of the food consumed in the region.

Banks are a significant source of capital for agribusinesses in Asia. Between January 2016 and December 2020, selected companies received US$22.6 billion in loans and underwriting attributable to their agribusiness activities from financial institutions active worldwide, according to FFA’s research. The majority is provided by financial institutions with ASEAN, with the largest creditors being from Japan, Singapore and Malaysia.

Dogged with problems

The agriculture and food production sectors are at a critical juncture as they meet the demand of growing populations, rising wealth, and changing diets in the region while ensuring a sustainable and resilient future.

But social issues have become rampant with the sector’s rapid growth. Agri-companies in Asia, and the banks supporting them, have been tarnished with a legacy of poor land management and exploitative working practices. Modern slavery, forced and child labour, gender inequality, informal and precarious work remains prevalent in agribusiness in the region.

Other violations include low wages, dangerous working conditions and discrimination, including gender-based discrimination. These issues are compounded by little or no rights to land. Change is made harder by the fact that the right to organise is becoming increasingly difficult in parts of Asia with workers intimidated, or attacked, to deter such gatherings of protest. Farmer and farm labourers have limited bargaining power as a result.

Women, as well as people of other marginalised group are disproportionately impacted by the irresponsible business conduct of some agribusinesses, according to FFA. They face discrimination in the access to land, capital, inputs, information and training. Most inheritance systems disadvantage women in developing regions, including their right to be recognised as farmers.

Lax regulatory oversight and social frameworks

A legacy of socio-cultural issues, coupled with weak policy implementation, have a large role to play in the sustained inequalities in the agricultural sector.

These social issues do not exist in isolation. Labour-intensive and with huge differences between countries in the region, the social policy weak spots in agriculture are often multi-layered and complex, according to Bernadette Victorio, regional programme lead, Fair Finance Asia.

Banks are struggling to measure and quantify the impact of social issues in the sector. Unlike markers measuring greenhouse gas emissions and their impact on the climate, it is harder to quantify social standards. “That’s another reason why there’s not a lot of attention,” Victorio told Eco-Business. “In technical terms, there are no accounting standards”.

Gender equality remains a blind-spot for financial institutions. Most (90 per cent) of the financial institutions assessed by FFA-GRAISEA do not disclose information about how gender issues, and particularly women’s rights, are addressed in their relationships with clients or investee companies.

A 2019 investigation conducted by FFA into banana production in the Philippines uncovered the violations of workers’ rights by firm, Sumifru (Philippines) Cooperation, originally established by Japanese trading house Sumitomo Corporation. It found that state-owned banks including Land Banks of the Philippines, fostered unfair and inequitable relationship between farmers’ cooperatives and large companies like Sumifru.

Meanwhile, frameworks established by banks remain voluntary and lack any enforcement muscle.

Foreign banks, for example, will sometimes defer to country-level regulatory frameworks in place to govern social practices, superseding their own, often more stringent, benchmarks. With discrepancies in compliance and oversight across the region and a chasm between investor expectations and the delivery on the ground, social issues in the agriculture sector persist.

Australian and New Zealand Bank Group Limited (ANZ Group) came under fire for its involvement with Phnom Penh Sugar in Cambodia. The project allegedly evicted families with little compensation, taking their land and farms to make way for a controversial sugar plantation and refinery. In February 2020, ANZ agreed to compensate the hundreds of Cambodian families by paying them profits from the loan. After being grilled by Australian regulatory bodies, it became clear that ANZ fell short of its own international standards.

“Financial institutions continue to provide credit to agribusiness companies without implementing structural changes in their policies and processes to comply with international, regional and national sustainability standards and regulations,” according to the FFA-GRAISEA report.

Pressure is on

Pressure on financial institutions by investors, regulators and consumers to embed environmental and social risks into their policies has ramped up in recent years. Investor pressure is mounting on banks to ensure that ESG factors and associated risks are managed more consistently.

A 2019 S&P Global survey of 194 credit risk professionals working in banks and other financial institutions found that 86 per cent agreed that heightened investor demand is making it critical to consider ESG factors more fully in credit risk analysis.

Customers are also scrutinising where they put their cash – looking for banks that align with their views and beliefs. Millennials are increasingly interested in placing their bets on companies and fund with demonstrable ESG credentials, according to a recent survey by consultancy, EY.

If banks don’t act, they risk being exposed publicly serving a significant reputational and financial blow. Data from Sigwatch, an organisation which tracks NGO campaigning activity globally found that the number of campaigns targeting the financial sector have nearly doubled between 2011 and 2019.

Measure, train and include

With their financial heft, banks can play a key role in supporting a shift away from socially harmful practices in the agriculture and the food sector. Mapping the blind-spots in a bank’s policy is a good first step. Committing to internationally recognised human rights and labour rights would reduce ambiguity and ensure consistency.

Financial institutions also need to focus on building staff capacity to do the required audits and to devise and apply relevant ESG policies to the field, said FFA. This would help close the gap between theory and practice.

Better focus on financial inclusion would mean supporting smaller businesses, which might not be as lucrative, but tend to be aligned with sustainability practices. Demand for smallholder finance in the broader region stands at about US$100 billion annually with less than a third of this demand being currently met, according to the World Wide Fund for Nature. Bringing smallholders into the investment portfolio would also foster competition.

“It also benefits governments when the invisible market or informal markets are better seen by government agencies when they can access financial systems, either through approaches to credit or financial literacy and inclusion,” Victorio said.