Over the past 30 years, more than 50 per cent of reefs have disappeared and more than 75 per cent are damaged. Another 40 per cet of the remaining coral may disappear in the next 30 years, unless there is a global conservation rethink.

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

With every reef lost, essential food, protection and spawning grounds for marine life disappears and biodiversity decreases. With coral on the wane across the globe, the marine food chain is under strain and commercial fishing stocks are threatened.

Anuar Abdullah studied oceanography in Florida and began looking at ways to regrow coral in the Perhentian Islands in Malaysia in 1981. At first the 61-year-old Malaysian’s efforts proved futile.

“Locals used to come and watch me on the beach, tying bits of coral to rocks and they laughed. For twenty years, I observed the behaviour and life cycles of coral. And at first, I failed to grow coral. But looking back, I needed to fail many times to get it right in the end. On land we have been planting, growing and cultivating trees for thousands of years. With coral, we have only recently become aware, in the last 35 years, of the need to take action.”

Abdullah persevered and eventually came up with a new way to regrow coral.

“

We worked on reefs destroyed by typhoon Hayan in the Philippines in late 2013, which suffered 99.8 per cent damage. But we still managed to bring the coral back.

Anuar Abdullah, founder, Ocean Quest

Anuar Abdullah, 61 year-old coral conservationlist. Image: Anuar Abdullah

“I realised that artificial reefs are a mistake. Adding anything man-made to the reef environment such as metal grids, PVC piping or leather, doesn’t make sense as these structures eventually fall apart and are potentially poisonous. They also cost money – fabricating structures and transporting them to the sea and then placing them in the water is not cheap.”

Abdullah developed new techniques and methodologies that required no frames to be added to the marine environment. Instead, he used lumps of dead coral to grow new coral.

“Back in the 1980s, many reefs were suffering, but the decline really picked up in the 1990s when Southeast Asian economies developed rapidly and when mass tourism started to make inroads. Businesses back then didn’t think about sustainability and often built on top of reefs, to extend available land. Now there’s a growing awareness that the coral needs to be saved.”

By 2010, Abdullah had refined his technique and founded coral conservation group Ocean Quest. Initially active in Malaysia, the organisation soon began to work in Thailand, Indonesia and the Philippines, and began taking on projects outside Asia in 2017.

“As we are registered as a social enterprise, we are primarily engaged in training. We work with local stakeholders and we engage the local community on every coral reef rehabilitation project. In fact, we only work with governments if they come to us and ask us for help. It is much easier working with resorts or associations. Of course, our strategy depends on many factors. Not every reef is the same. Local climate and the amount of damage done, play a role in how we work. The measure of our success becomes apparent through how much a project is able to give back to the community and the environment.”

Ocean Quest enters four-year agreements with stakeholders. The organisation then typically builds a coral nursery and trains local people to look after it and how to help the coral grow.

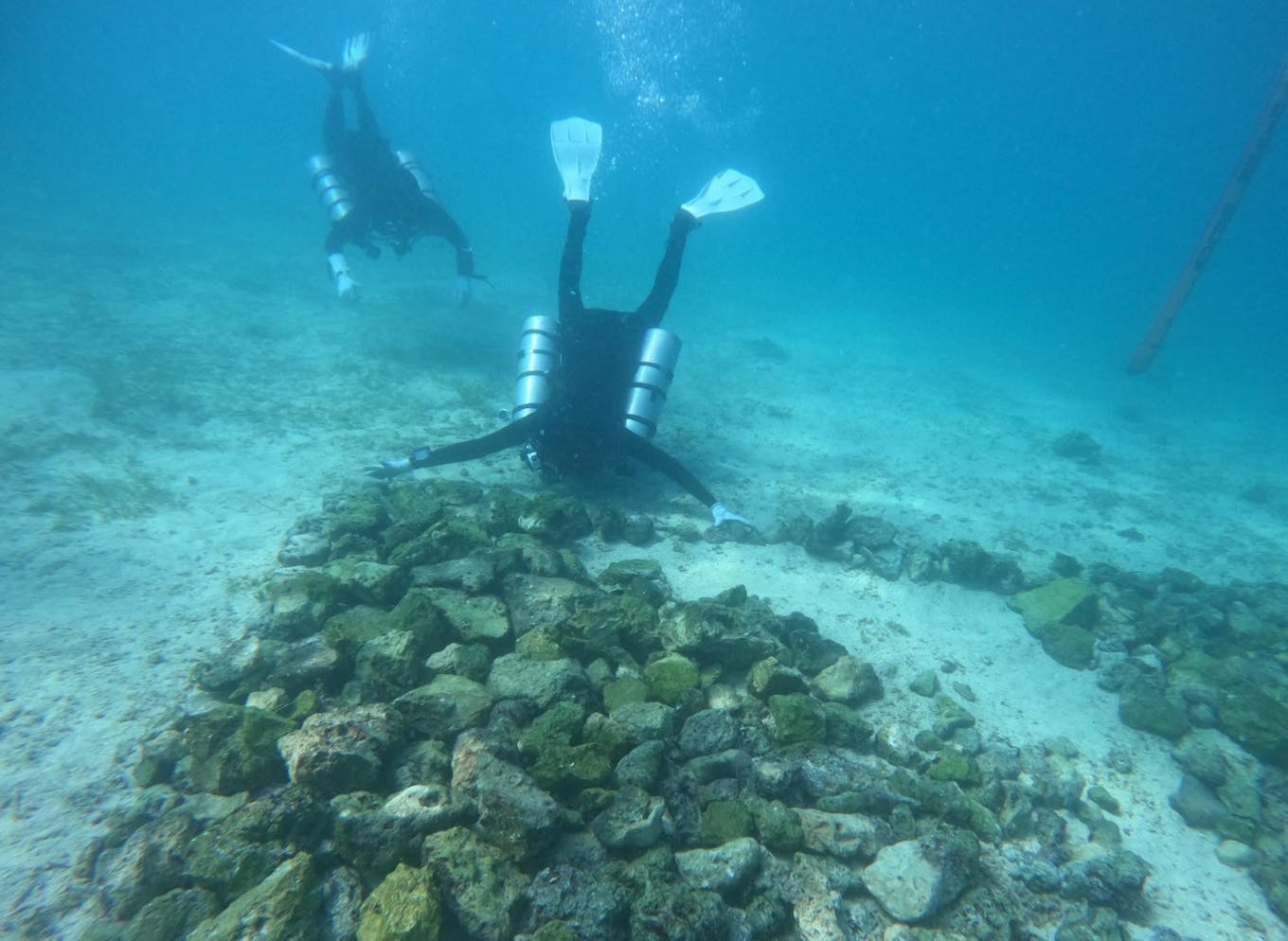

“We take direct action without delay and work in hectares, acres and square kilometers. Our approach is industrial. We rehabilitate entire reefs. We have developed a simple education system that allows the public to take part in coral reef rehabilitation and we apply this method everywhere we go. We worked on reefs destroyed by Typhoon Haiyan in the Philippines in late 2013, which suffered 99.8 per cent damage. But we still managed to bring the coral back.”

Ocean Quest working on a reef devastated by Typhoon Haiyan. Image: Ocean Quest on Facebook

Ocean Quest currently runs 13 projects around Borneo. Off the island’s west coast on Sepanggar Island, the local communities cut all the sea grass three years ago that grew along the coast line. It had made the beaches look dirty. As a consequence, run-off from monsoon rains washed straight into off shore coral reefs, the filtering function of the sea grass gone. The reefs silted up and died.

“There’s no point regrowing coral here unless we also regrow the sea grass. We need to look at the bigger picture, so we can develop a particular strategy for every situation we encounter. So, we’re now engaged in two projects – first regrow the sea grass, then regrow the coral.”

Reefs die for a variety of reasons, all of them man-made. On the opposite side of Borneo at Mabul Island, Ocean Quest was faced with an entirely different challenge. The reef here has been overharvested by fishing with dynamite and poison.

Work to coral restore reefs at Maya Bay. Image: Ocean Quest Thailand

In Thailand, Abdullah initiated the rehabilitation of Maya Bay, famous for having served as a location in Leonardo DiCaprio’s The Beach movie (2000). The Thai government closed Maya Bay in 2018 after decades of mass tourism had destroyed the coral and alienated the resident reef sharks. Abdullah created a tourism sustainability strategy for the 300-metre-long bay. Working with the national park and private stakeholders, Ocean Quest developed a sustainable tourism strategy and initiated coral growth. The bay reopened in spring 2022, with restrictions – visitors are no longer aloud to swim and long tail boats are not allowed into the bay. But visitor numbers were still too high and Maya Bay is closing again over the summer.

“The national park largely followed our recommendations. But they need to stay the course, if Maya Bay is really to recover,” Abdullah told Eco-Business.

With large projects running near the Red Sea resort town Hurghada in Egypt and in French Polynesia, Abdullah spends most of his time on the road. He’s particularly excited to travel to the Mergui Archipelago in the Andaman Sea, off the coast of Myanmar. Here, coral grounds have been devastated by dynamite fishing and a resort island has asked Ocean Quest to take a look at what can be done to restore coral in the area.

In November, Ocean Quest will be presenting its work at the 2022 United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP27) in Egypt, to convey the urgency of coral conservation to a global audience.

After 40 years of research, failure and success, Abdullah remains an optimist at heart. “Although a fair amount of the ocean’s paradise is broken, Ocean Quest made it its purpose to tend to it and heal it through conservation.”