In May this year, mercury in Singapore hit 38.6 degrees Celsius, recording the island state’s second-highest temperature on record. In Malaysia, when massive floods hit several states late last year, towns and villages were swamped with water. Power and communications were knocked out, and rain-induced landslides made things worse.

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

For many Southeast Asians, their concern about extreme weather is becoming personal and hitting closer to home. When asked to list “the three most serious climate change impacts” that their country is exposed to, a regional perception survey now finds most respondents choosing floods (22.4 per cent), heatwaves (18.1 per cent) and rainfall-induced landslides (12 per cent).

Loss of biodiversity, which had consistently ranked second in past surveys, has now slipped from the list, with percentages of respondents from the different countries who consider it serious hovering at only about 10 per cent.

“Extreme weather impacts are being felt across the region more acutely and immediately than before, which is why heatwaves and rainfall-induced landslides, considered fast-onset events, have risen to the top of the list, replacing longer-term, slow-onset impacts like biodiversity loss and sea-level rise,” said Sharon Seah, senior fellow and coordinator of the Climate Change in Southeast Asia Programme at Singapore’s ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute, which released the survey results on Thursday.

“Climate worries are elevating year-on-year as the region continues to face extreme weather impacts, but governments, businesses and other stakeholders are seen to be slow and ineffective in their responses,” she added.

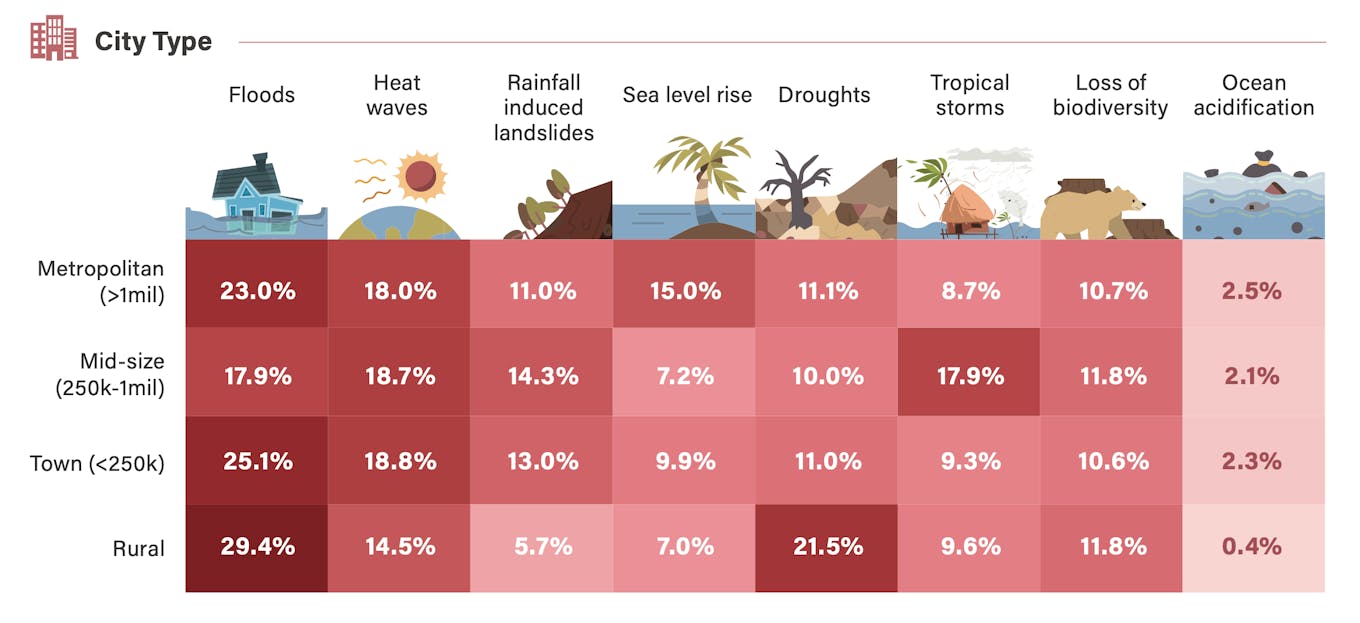

Sentiments on climate impacts vary depending on the type of city each respondent resides in. Those in metropolitan cities are concerned about sea level rise. Image: Southeast Asia Climate Outlook Survey 2022

Conducted annually, the Southeast Asia Climate Outlook Survey 2022, designed to capture the attitudes and sentiments of citizens in the region towards climate change, is in its third edition this year.

Among the nearly 1,400 respondents who answered the survey between 8 June and 12 July, Cambodians and Malaysians were most concerned about flooding. The survey also found those in metropolitan cities with population sizes of more than a million highly concerned about sea-level rise.

Heatwaves were Myanmar’s biggest problem, with nearly 30 per cent of respondents registering the impacts from heatwaves as serious. It ranked as the top concern for mid-sized cities in Southeast Asia with resident sizes of 250,000 to 1 million.

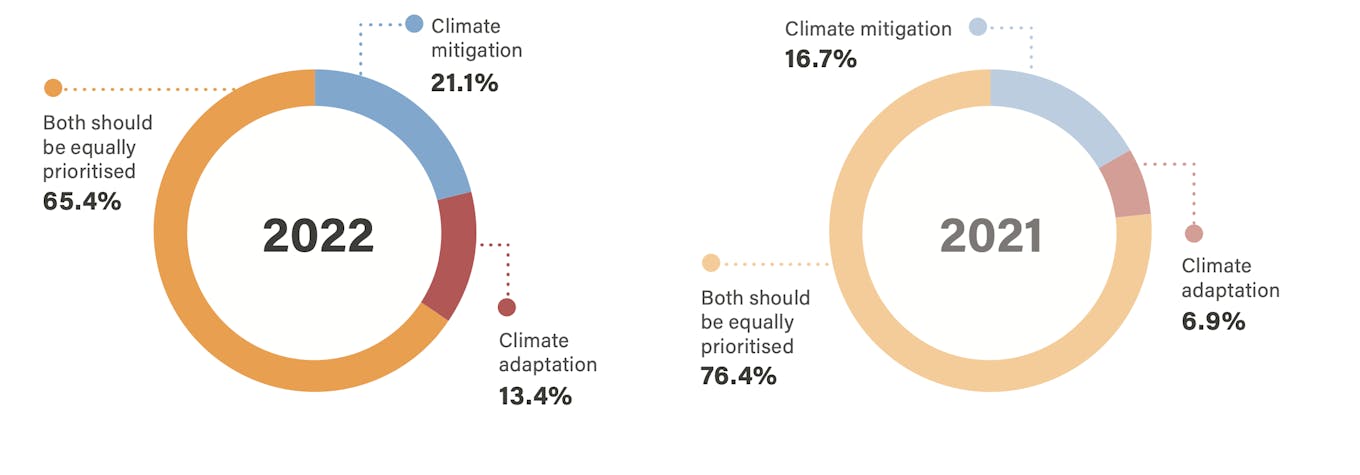

Support for climate adaptation over mitigation has increased compared to last year’s survey. Image [Click to enlarge]: Southeast Asia Climate Outlook Survey 2022

Support for climate adaptation (13.4 per cent) over mitigation increased almost two-fold compared to last year’s survey. “This could be due to the rising concerns of climate disasters in the region,” said ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute in the report.

Responding to the survey results, senior campaigner of Greenpeace Southeast Asia Wilhemina Pelegrina said that while it is good that there is growing recognition in the region of the impacts of climate change, which could propel urgent action, countries need to take action to address biodiversity loss and climate change at the same time.

“We do not see this as an ‘either or’ issue. Rather, both issues are important, and we are at a juncture where we have to address these multiple crises – of biodiversity, of climate, and of health,” she said. “Southeast Asia has very rich biodiversity…and we need this richness to adapt to climate change.”

Mentioning COP15, the global biodiversity conference to be held in Montreal in December, Pelegrina said that “a lot is being asked” from Southeast Asian nations – for them to be held accountable for taking more urgent action to tackle loss of biodiversity, yet at the same time, developed countries with binding obligations to provide new and additional financial resources for developed countries are themselves “stonewalling the discussions”.

“It is sad to see how biodiversity loss remains unabated and how the injustices have continued.”

“

We do not see this as an ‘either or’ issue. We are at a juncture where we have to address these multiple crises – of biodiversity, of climate, and of health.

Wilhemina Pelegrina, senior campaigner, Greenpeace Southeast Asia

A key issue that Southeast Asia needs to confront is continued deforestation, with tropical rainforests being logged and burnt to make way for oil palm plantations and mining, displacing indigeneous communities, said Pelegrina. Loss of agricultural biodiversity, which results in limited choices for consumers “at a time when we need diversity in food sources as we recover from the current pandemic”, is of concern too.

Malaysian ecologist, diplomat and biodiversity advocate Zakri Abdul Hamid said that one of the top issues when it comes to protecting biodiversity in Southeast Asia is to establish more protected areas in the region beyond the usual national parks. Indigenous and local communities can act as custodians of these areas, and their roles need to be recognised and formalised by organisations such as the United Nations, he added.

According to survey results, close to a third of the respondents identified extreme weather events as the main threat to their country’s food supply.

Coal retreat?

The survey also finds the ongoing Russia-Ukraine war altering attitudes of Southeast Asians towards coal and fossil fuel consumption. When asked if Asean countries should phase out coal consumption either immediately or by 2030, about 72.5 per cent of respondents said yes, a slight decline from the 79.0 per cent which gave a positive answer in last year’s survey.

“This may indicate that rising energy prices caused by the war has given rise to a more favourable perception of the use of coal,” said the report.

Only 6.7 per cent of the respondents support the removal of fossil fuel subsidies, when asked what governments can do to reduce carbon emissions, a decrease from last year’s 7.6 per cent. This is even as almost eight in 10 respondents say reduction of dependence on fossil fuels, though painful, is beneficial to Asean economies in the long term.

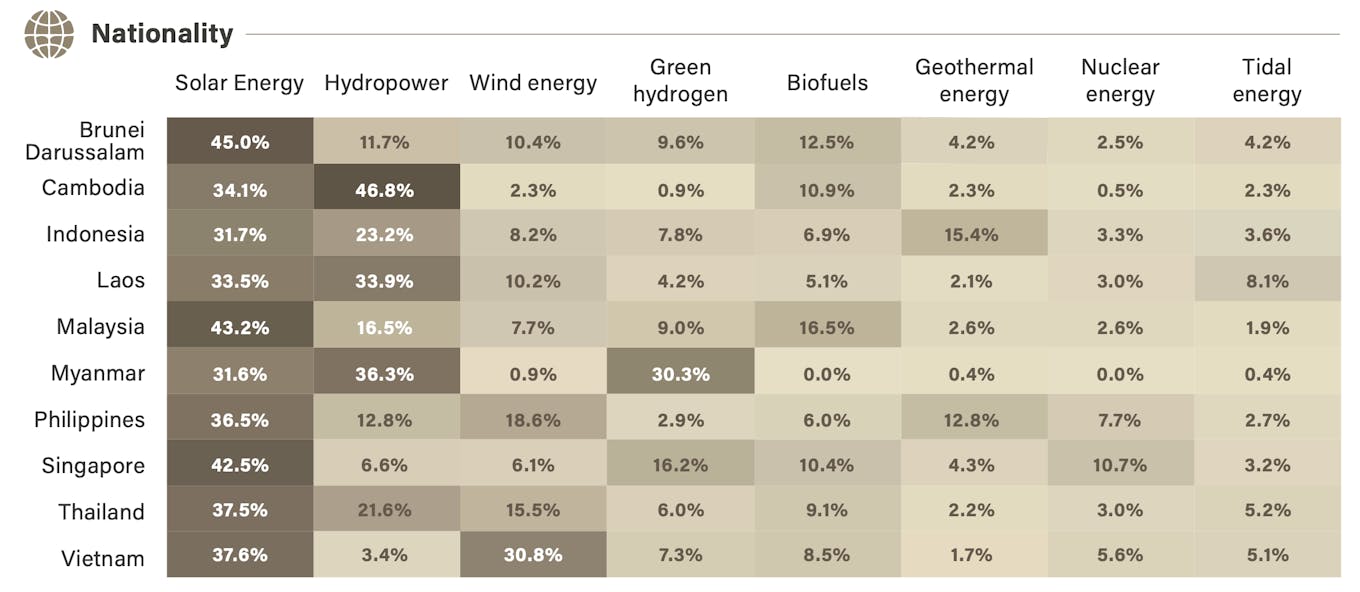

Responses were varied when people were asked which sources of clean energy have the greatest potential in their country. Image: Southeast Asia Climate Outlook Survey 2022

Prompted by countries opting for a more nuanced stance of a coal “phase down” instead of a complete “phase out” at last year’s COP26 Glasgow summit, the survey also asks a new question about whether Southeast Asians agree with an urgent phase out. About 62.4 per cent of respondents want Asean countries to stop building new coal plants immediately, with sentiment being strongest in Cambodia, Malaysia and Philippines.

The largest group of respondents in disagreement were from Myanmar and Vietnam.

Singapore should take on climate leadership role

Asean has historically relied on fossil-fuelled power plants to fulfil its energy demands. A 2020 report by the Asean Centre for Energy estimated that Asean’s coal power capacity is expected to reach 259 gigawatts, up from 79 gigawatts in 2018, and about 3.6 times the current capacity, indicating that coal could still see robust growth in the power mix.

Respondents of the survey were also asked which Southeast Asian country is best-placed to become the region’s climate leader. Singapore came up top, with over half of the respondents (53 per cent) believing that the city state had the potential to take up a stronger leadership role. It was the top choice for respondents from every country, with the exception of Indonesians, who were more likely to choose their own country for the leadership role.

Filipinos showed the strongest sense of urgency in addressing the climate threat and were the most willing to accept a carbon tax, even though the report noted that there was low awareness among respondents that the country does not yet have a concrete net-zero target.

When asked what the biggest obstacle to decarbonisation is in their respective countries, 50.9 per cent of respondents cited insufficient financial resources, and 50.4 per cent felt that countries lack the research and development capabilities, technology and expertise to push related efforts. Malaysians said that the key barrier was a lack of political will from their government.