Vanilla, a vining orchid, is arguably the second most expensive spice in the world, behind saffron, and seen by most farming communities as an extremely lucrative crop. Even though its commercial variety does not flower well in Cambodia, the country has recently looked into cultivating it – under highly-controlled environments and with the use of advanced technology.

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

On a 16-hectare plot in the Cambodian coastal town of Sihanoukville, Dara Chan, a Cambodian-American who recently relocated back to his home country, is developing a “vanilla research lab” to commercially propagate the crop. In addition, he told Eco-Business that he is prototyping smart farm technology for irrigation, as well as temperature and humidity sensors that can automate turning on and off pumps and fans.

Chan is part of a growing community of start-up entrepreneurs excited and optimistic about the prospects of agritech in Cambodia, propped up by strong investor interest. Even as official data on agritech developments are still lacking – a last-known set of statistics point to how the number of active agritech startups has more than doubled from 2018 to 2021– and not updated, industry observers point to the major international investment deals that emerging Cambodian-based agritech startups have been able to clinch in recent years as positive signs.

“

Farmers make little money and their only option is to go to micro-lending institutions and get into a cycle of debt. Then they feel the crops aren’t working, so they cut them down and that makes the soil bad for the harvest of new crops. This is the overall state of agriculture in Cambodia.

Toffer Briones, director for entrepreneurship and innovation, Impact Hub Phnom Penh

In mid-2022, Azaylla, an agriculture supply chain platform, received an undisclosed amount of pre-series A funding from Singapore-based investor Insitor Partners. The Cambodian government is also backing the push to modernise its expansive agriculture sector and drive sustainability efforts with a 2030 sectoral master plan.

Chan said his ambitions to “revolutionise the agriculture sector” in Cambodia are driven by a wish to elevate the livelihoods of Cambodian farmers, as poverty reduction efforts often hinge on how productive the farming sector is.

Last December, Chan, who spent four years working in the automated vehicle industry in Silicon Valley, visited his family’s durian farm in Veal Renh in Preah Sihanouk province. He noticed that many processes were still done manually and that horticulture was input-intensive, with high volume of water, fertilisers and pesticides being used.

“The seed was planted for me to wrap up my old career and take the plunge,” he said. “I feel strongly that agriculture is key to making development impact. Agritech can provide the tools to improve productivity and yield, while creating high-paying and highly-skilled jobs.”

The lab that Chan runs is conducting trials to also grow saffron and ginseng – all high-value crops – in refrigerated insulated containers. “We are troubleshooting existing issues so that our farmers can be successful,” he said.

Vanilla, which Dara Chan says has a lot of potential in Cambodia, as it has a very high potential output per hectare. (left) and Chan at a durian farm (right). Image: Dara Chan

Toffer Briones, director for entrepreneurship and innovation at Impact Hub Phnom Penh, which works with a community of youth and start-ups, noted that the agritech start-up culture is much stronger now, as compared to 10 years ago. “Education has vastly improved and younger people are more tech-savvy,” he said, adding that Cambodia still has a very young population.

Agriculture stands as one of Cambodia’s four main economic pillars, providing 39 per cent of employment nationwide and contributing 22.85 percent to the nation’s gross domestic product (GDP). However, climate change and other growing pressures threaten the sector’s future.

Many of the emerging start-ups are looking to tackle these problems with innovative technologies. ” According to Sophoan Phean, national director of British-founded charity Oxfam in Cambodia, which operates the BlocRice Project, farming is being modernised in various ways. The project aims to increase the income of organic rice farmers by enhancing supply chain transparency through blockchain technology to improve farm productivity and reduce costs.

Precision agriculture and fintech solutions

Irrigation and water management is one key area where technology is utilised in Cambodia, said Phean, citing instances where farmers adopt technologies such as drip irrigation, sprinkler systems and water sensors to optimise water usage and reduce water waste.

Precision agriculture sees farmers use advanced technologies including GPS (short for Global Positioning System), remote sensing and drones to gather data on soil conditions, crop health and pest infestation. “This data enables farmers to make informed decisions regarding fertiliser application, irrigation, and pest control, resulting in optimised resource allocation and improved crop yields,” noted Phean.

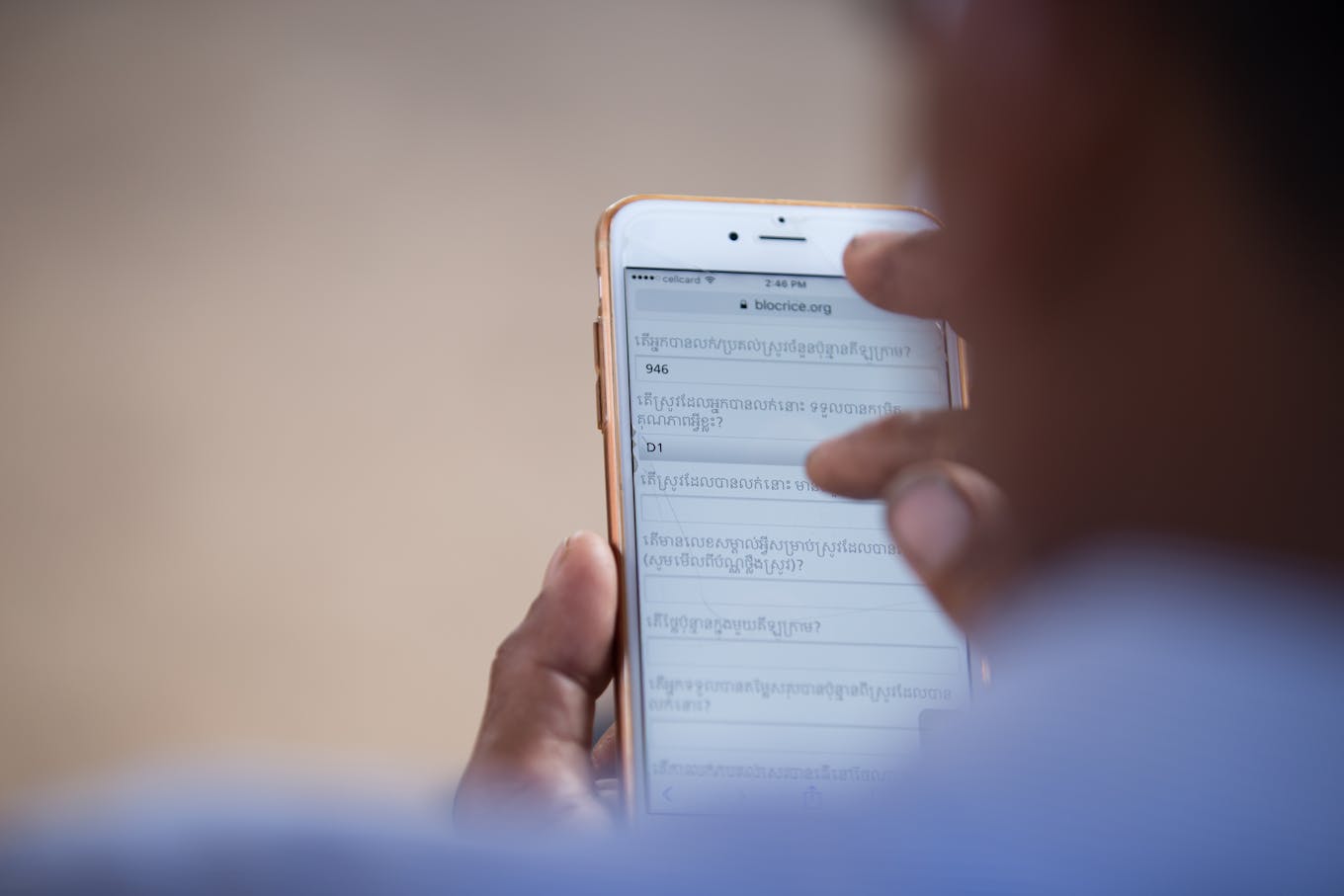

In addition, the widespread use of smartphones has opened up opportunities for farmers to access agricultural information and services through mobile applications. These apps provide real-time weather updates, market prices, pest management advice and access to financial services, empowering farmers with information for decision-making.

A farmer accessing agricultural information and services on a Cambodian language mobile app. Image: Oxfam in Cambodia

Fintech solutions, such as mobile banking and digital payment systems, are facilitating financial transactions for farmers too, said Phean. These technologies enable them to access credit, receive digital payments and engage in online marketplaces, reducing reliance on traditional banking systems and increasing financial inclusion.

Impact Hub Phnom Penh, on the other hand, has been instrumental in the agri-tech start-up drive, running various programmes, including SAAMBAT Digital Agriculture Accelerator. The six-month programme, which is about to launch its second cohort, supports entrepreneurs to strengthen their minimum viable product, gain customer validation and accelerate their viability.

However, Briones said while accelerating factors such as a rise in education and a tech-savvy younger generation, hurdles remain with regard to technology adoption in Cambodia. There is still a large group of farmers who rely on traditional techniques used by their forefathers. Economic and literacy constraints also lead to them making less-than-ideal decisions.

Briones used an example to illustrate his point. He knows of a farmer who recently reaped success from mango farming, and noted that it was not before long that neighbouring farmers followed suit, planted the same fruit, which led to oversaturation and a slump in prices, forcing everyone to sell the produce at lower prices to illegal buyers in Vietnam and Thailand.

“Farmers make little money and their only option is to go to micro-lending institutions and get into a cycle of debt. Then they feel the crops aren’t working, so they cut them down and that makes the soil bad for the harvest of new crops. This is the overall state of agriculture in Cambodia,” Briones said.

Poor tax policies and incentives for agricultural export further exacerbate the issue, along with the expense of importing equipment and poor infrastructure, noted Briones.

Agriculture is a key economic pillar in Cambodia, providing 39 per cent of employment nationwide. However, climate change and other growing pressures threaten the sector’s future. Image: Oxfam in Cambodia

Planting seeds for growth

Oxfam in Cambodia also faced challenges while implementing its BlocRice Project. Motivation was one major issue, along with a lack of time to input required data into the application.

“The input of data requires additional efforts from farmers, and farmers need to be able to read and write to collect the needed data for the system. This requirement can be a challenge for some small-scale farmers,” said Phean.

Poor internet connection and limited technology infrastructure in remote rural areas remain limited for small-scale farmers, posing additional challenges, she added.

Neak Sokkim, a 20-year-old smart technology start-up founder, told Eco-Business that she is familiar with the challenges that farming communities in Cambodia face. Raised in a family of farmers, she witnessed how inefficient farming methods were. “I used to help my parents farm and it was a lot of time and labour. For example, when they irrigated the crops, it was mainly guess work. No one knew how much water they were using,” she said.

Sokkim, a fourth-year Engineering undergraduate with a major in IT, started developing a tool for farmers to automate crop irrigation in her freshman year. She then started CAM-Science, which provides a fully-integrate IoT (Internet of Things) and mobile app that aims to help Cambodian farmers increase crop yields and mitigate against adverse weather and climate conditions.

CAM-Science, which now employs 13 people, is one of the four start-ups to be selected for the first SAMBAAT cohort.

“Technology is increasingly important to make farming more efficient,” said Sokkim. “It’s not just important for farmers, but for the world’s food production. Agritech in Cambodia is essential, especially for smallholder farmers, and it is definitely the future,”