Although the rates of their loss are in decline globally, mangroves in Southeast Asia today continue to face persistent man-made threats, experiencing loss rates twice the global average, an international team of researchers has found.

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

Driving such rapid deforestation are the mangrove-rich region’s rising aquaculture, rice and palm oil farming, industrial activity and coastal development, reads the study, led by National University of Singapore (NUS).

Early twenty-first-century global mangrove destruction rates have been almost 10 times lower than those reported for previous decades due to better protection and shrinking forest areas available for conversion.

But the future of mangroves in Southeast Asia, home to almost one third of the planet’s mangroves, is uncertain, with coasts still being stripped of these salt-tolerant forests in nations such as Myanmar, Malaysia, the Philippines and Indonesia.

“

You can get a lot of rent from natural systems if you convert them to rice, rubber or oil palm.

Edward Webb, associate professor, Department of Biological Sciences, National University of Singapore

The study, published in the journal The Annual Review of Environment and Resources, shows that Myanmar’s annual mangrove loss rates are the region’s most alarming in percentage terms, followed by Malaysia and Indonesia. At 0.5 to 0.7 per cent, they are four times higher than the global average.

Myanmar lost a staggering 60 per cent of its mangrove extent in the last two decades, a loss rate much higher than previously estimated, found another new NUS-led study that appeared in the journal Environmental Research Letters.

“Myanmar is currently a global hotspot of mangrove deforestation, primarily due to conversion to rice agriculture,” said Daniel Friess, associate professor at NUS’s department of geography.

“The rest of Southeast Asia has seen a reduction in mangrove loss in recent decades, but mangroves are still threatened in many countries across the region,” he told Eco-Business.

No respite in sight

Mangroves—shrubs and trees that straddle the land and sea in tropical and subtropical regions—account for less than 1 per cent of the earth’s tropical forest area, but they provide vast environmental and socio-economic benefits.

Not only do they serve as nurseries for fish, crab and shrimp, they also shield coastlines from storms and tsunamis and suck carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, storing it in their wood, roots and soil.

Research shows that mangroves’ capacity to trap carbon far exceeds that of rainforests by area, making them an important buffer against global heating.

Hundreds of millions of coastal dwellers around the world depend on mangroves as a source of food and wood to build homes and fuel cooking fires. The goods and services that mangrove forests support are worth an estimated US$2.7 trillion each year.

But in the past decade, mangroves have been vanishing at rates faster than coral reefs and tropical rainforests, although their destruction receives less attention. Today, more than 35 per cent of the world’s mangroves are already gone.

Commodity production has been the leading cause for mangrove felling in Southeast Asia, shows the new research.

Almost one third of all mangroves lost from 2000 to 2012 were cleared for extensive development of shrimp farms—in response to skyrocketing appetite for shellfish in the United States, Europe, Japan and China—while 22 per cent were converted for rice and 16 per cent oil palm plantations.

With Southeast Asia’s population on the rise, new houses, hotels or other infrastructure popping up along the coast have fueled direct habitat loss, and so have pollution and the over-extraction of timber, fuelwood and charcoal by a growing number of coastal dwellers.

Direct habitat loss isn’t the only issue. The aquaculture sector has in recent years increased the use of pellet feed, hormones and antibiotics to boost production, discharging effluents that pollute seawater and harm surrounding mangroves as well, leading to habitat degradation.

The problem is that the value of these forests by the sea faces strong competition from converting the land to other more profitable uses, said Edward Webb, associate professor at NUS’s Department of Biological Sciences.

“You can get a lot of rent from natural systems if you convert them to rice, rubber or oil palm. They are lucrative, and there is a huge pressure to expand into these forests and to use mangrove resources,” he said.

“The ecosystem services that mangroves support, such as carbon sequestration and shoreline protection, are not evident on a day to day basis. They are only important when tsunamis or storms occur, so local benefits of conversion outweigh other benefits,” he observed.

While deforestation in many Southeast Asian nations has slightly abated, it is estimated that mangroves will keep disappearing at alarming rates in Indonesia, Malaysia, Vietnam and Myanmar for decades to come.

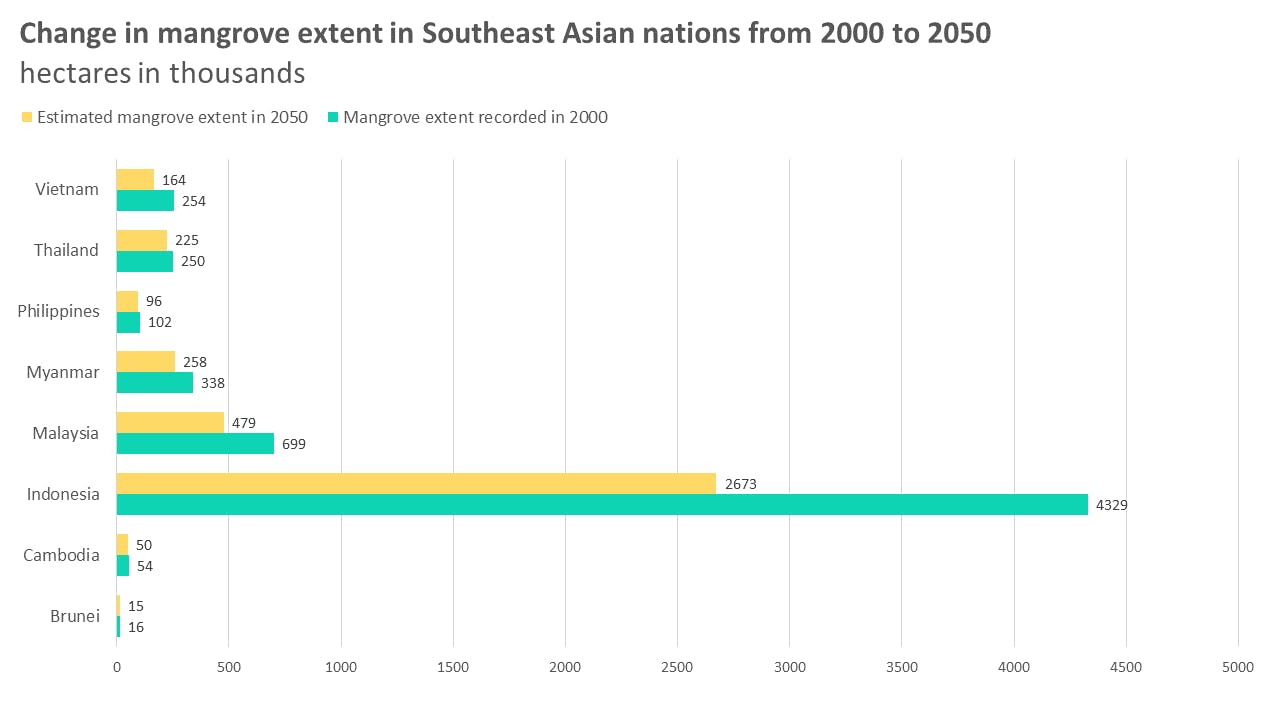

Eco-Business graphic: Change in mangrove extent in Southeast Asian nations from 2000 to 2050. Source: Brander et al., 2012

In Indonesia, which is home to the world’s largest mangrove forests, and the world’s mangrove destruction hotspot in absolute terms, aquaculture production is expected to grow by 7 per cent per year until 2030, with government targets even higher.

Another rising deforestation driver is palm oil. Despite efforts to satisfy production increases by raising yields in current plantations, expansion will likely open new deforestation frontiers in regions such as Papua, where mangroves remain largely intact, the research shows.

In particular, Myanmar’s nascent oil palm sector poses a threat to mangroves, with government targets to become self-sufficient in the commodity.

Even in highly developed Singapore, current policies favour ongoing seaward expansion of urban land use to support a growing economy and population that will come at the expense of the city-state’s few remaining patches of mangrove forest.

Since the 1950s, the prosperous city-state’s mangrove extent has declined by more than 90 per cent.

Conservation challenges

The fate of Southeast Asia’s mangroves is tied to the strength of policies and implementation of conservation measures. Today, the importance of mangroves is becoming better understood, and their protection has moved up the international policy agenda.

“

We can continue to get the benefits provided by mangroves without losing them.

Daniel Friess, associate professor, Department of Geography, National University of Singapore

“There are lots of efforts underway to figure out how development and mangroves can coexist, so we can continue to get the benefits provided by mangroves without losing them,” Friess told Eco-Business.

But of the mangroves that remain, only about one third is legally protected, and in many regions, nature groups are fighting a losing battle to preserve them.

Even as the Global Mangrove Alliance, an international coalition of conservation groups and government agencies, pushes for a target to increase global mangrove extent by 20 per cent by 2030, funding and enforcement that effective protection requires are scant.

In Myanmar, for instance, conservation initiatives have grappled with a lack of funds ever since many countries and international organisations turned off the aid tap in the wake of the Rohingya crisis five years ago, said Maung Maung Than, country director for Myanmar at international community forestry-focussed non-profit The Center for People and Forests (RECOFTC).

Despite efforts to preserve mangroves, loss rates in the country still far exceed conservation gains, although the rate of deforestation has slightly decreased. The mangrove-rich Irrawaddy Delta in southern Myanmar is at particular risk, he said.

“Most local communities in the region are poor and depend on mangroves for their livelihood. If we don’t create alternative income for them, the remaining mangroves in the delta will be lost,” he told Eco-Business.

RECOFTC is collaborating with the Myanmar government to implement community forestry programmes, granting coastal dwellers access to land in return for the guarantee that mangroves will be protected.

Another problem is that rehabilitation of coasts stripped bare doesn’t work very well, as many planting initiatives are ill-informed, the new study shows.

Often, fast-growing exotic species are planted—a poor substitute for native mangroves—while saplings planted in less favourable locations can be washed away by the waves, lowering success rates. In the Philippines, for instance, less than 20 per cent of nearly three million seedlings planted in rehabilitation efforts that cost $35 million in the 1980s have survived.

To ensure rehabilitation has an impact, it requires collaboration, said Friess.

“Governments need to be involved because often mangroves are on state land. Local communities need to be involved because they are closest to the ground and can rely substantially on the mangrove. NGOs can provide support and attention. Researchers can provide robust evidence and monitoring upon which to base management decisions,” he told Eco-Business.

But the best way to go would be not to cut down trees in the first place.

“Rehabilitation is not a quick fix, and restoring area and ecosystem service provision is challenging and expensive to undertake at scale. Protecting existing mangroves is more cost-effective and has better ecological outcomes compared to rehabilitating lost habitat,” the study reads.