By 2050, Singapore’s daily mean air temperature is expected to surpass its highest annual temperature to date of 28.4°C, according to the country’s third national climate change study.

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

Under the low emissions scenario adopted by Centre for Climate Research Singapore (CCRS), the research division of the city-state’s meteorological service, average air temperature on a typical day is forecasted to reach 28.9°C by mid-century – a 0.5°C jump from the record annual temperature the city-state hit in 2019, when it tied with 2016 as the hottest year in Singapore’s history.

The climate change study, otherwise known as V3, uses three global socio-economic pathways affecting greenhouse gas emissions to make climate projections for Singapore and the rest of Southeast Asia by end-century: the low emissions scenario (SSP1-2.6), medium emissions scenario (SSP2-4.5) and high emissions scenario (SSP5-8.5).

These pathways correspond to the shared socio-economic pathways used in the International Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) Sixth Assessment Report (AR6).

For the first time, the national climate change study introduces heat stress projections based on the wet-bulb globe temperature (WBGT), which is a more holistic measurement than air temperature as it also takes into account humidity, wind and solar radiation.

Health experts consider a high WBGT dangerous as human bodies shed excess heat primarily through the evaporation of sweat, which becomes less effective when humidity and air temperature are high.

In July last year, the Singapore government released its inaugural heat stress advisory, which alerts residents to the heat stress levels across the island, alongside recommendations for how they can modify their activities in response to the prevailing levels of heat stress.

Between 2018 and 2022, there were eight days with incidence of high heat stress, which in Singapore’s context is defined as a WBGT exceeding 33°C.

To reduce the risk of heat stress for outdoor workers, the Singapore government has made it mandatory for employers to give them hourly breaks when heat stress levels are high.

The number of days with periods of high heat stress is projected to increase by over sixfold by mid-century. Under the worst-case scenario where global emissions almost double that of current levels by 2050, high heat stress could be experienced almost all year round by end-century.

As a whole, Southeast Asia is expected to get 2.5°C to 6°C warmer in March, April and May – typically the hottest months of the year – with temperatures set to rise more over Myanmar, Thailand and Laos. All three countries shattered all-time records in 2023 when temperatures climbed upwards of 43°C in some places and reached a whopping 45.3°C in Thailand.

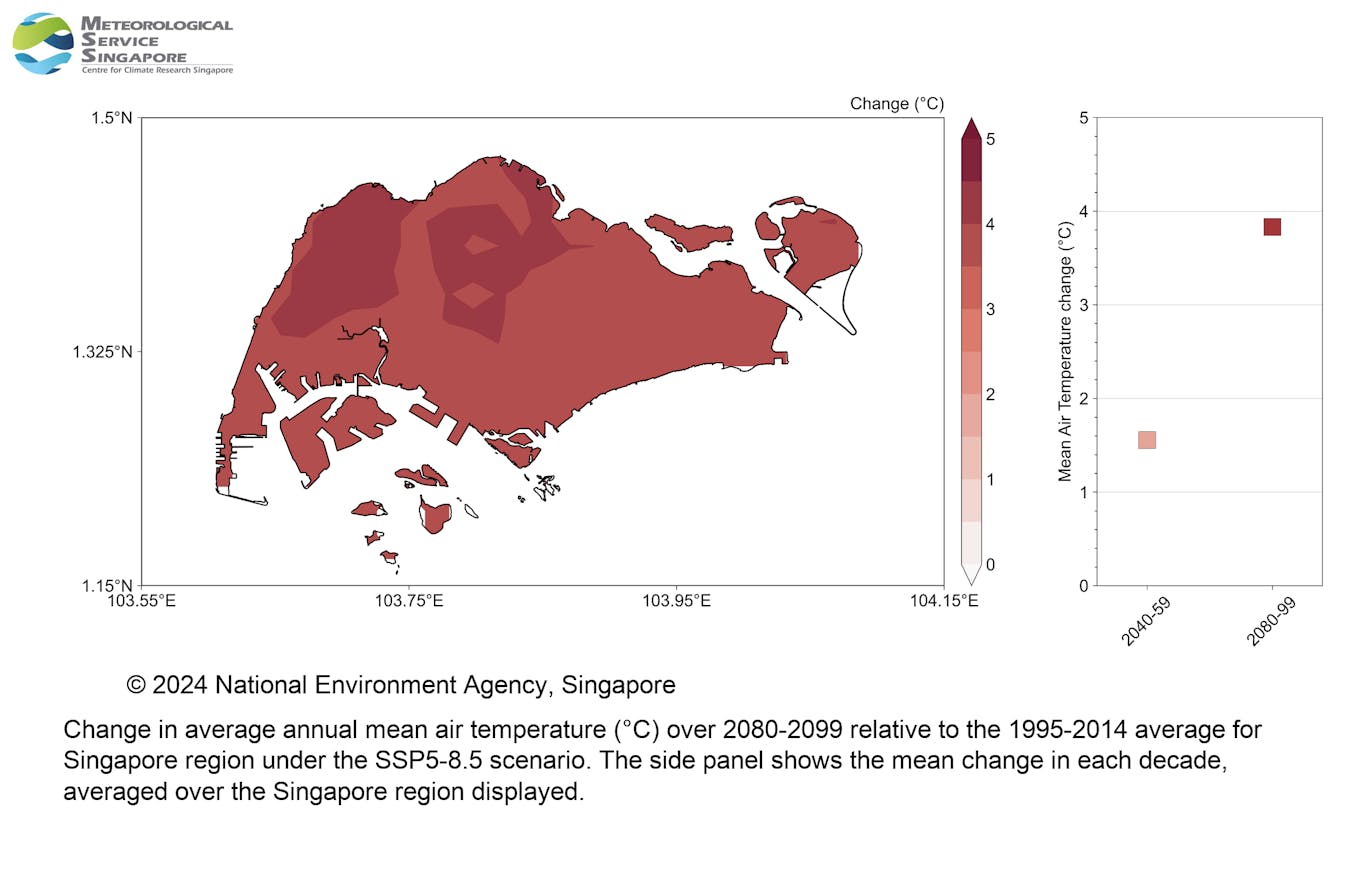

Climate projections for Singapore’s daily mean temperature via a new data visualisation portal, based on the V3 findings. Image: Metereological Service Singapore

Apart from higher temperatures, the study projected more wet and dry extremes by the end of the century. Rainfall during wet months are expected to increase by up to 58 per cent and fall by up to 42 per cent during dry months, compared to the baseline period between 1995 and 2014.

Hazel Khoo, director, coastal protection at the national water agency PUB said that what is critical is that future dry spells will be longer and more severe than the projected increase in rainfall. “This calls for us to look at the data very seriously to incorporate the projections into planning assumptions, so we can continue to develop plans to ensure a sustainable water supply for Singapore,” she said, speaking at the study’s launch event, on a panel discussing the new findings.

The agency is also studying the impact of higher wind speeds on waves and coastal surge events, she shared.

Higher sea levels than previously expected

As a low-lying island, rising sea levels pose the most immediate threat to Singapore. The V3 study forecasted that mean sea levels around the country could rise by 1.15 metres by end-century – an increase from the projections of up to 1m over the same time period in the last national study, known as V2, done nine years ago.

This difference “is primarily due to the better understanding of the contribution of the melting of the Antarctic ice sheets to global sea levels,” stated the joint press statement by the Ministry of Sustainability and the Environment (MSE) and Singapore’s Met Service.

Sea levels are projected to rise at even faster rates in Manila and Bangkok, at 1.6m and 2.2m respectively. Both cities are already flood prone, with Bangkok sitting only about 1.5m above sea level.

Singapore’s Urban Redevelopment Authority (URA) and PUB will soon embark on technical studies for their plan to build a 800-hectare “Long Island” to protect the city-state’s Eastern coastline against rising sea levels while providing for future land needs.

But concerns have been raised by environmental experts and activists about the potential long-term loss of biodiversity and environmental degradation in source countries where Singapore will import its sand from for this particular project.

Responding to Eco-Business’ queries, URA and PUB said in a joint statement that the project will be guided by technical studies and public engagement, which will include an environmental impact assessment. The planning and implementation of the project is expected to take decades.

“PUB will look at sustainable construction materials and construction methods, with the aim of lowering carbon emissions during the construction stage and reducing embodied carbon in the materials,” the statement said. Some examples of sustainable materials include mineralised carbon or recycled construction materials in concrete.

Khoo said that PUB works closely with CCRS, and that the latest sea level rise projections will be taken into account for Singapore’s coastal protection plans, including the “Long Island” project.

Apart from flood and coastal resilience, Singapore’s adaptation plans – which will be informed by V3 findings – will touch on six other risk areas: heat resilience, biodiversity and greenery, water sustainability, food resilience, public health as well as infrastructure resilience.

These plans include reviewing national building codes to ensure transport, telecommunication and energy infrastructure can withstand projected changes, such as higher temperatures and increased wind speeds.

Also speaking at the launch, Elaine Tan, director of research at the Centre for Liveable Cities, pointed out the need to build community resilience, and to look beyond hardware infrastructural considerations. “One thing we understand is that when a crisis hits, it is the community that gets together to take collective action before other formal channels are activated,” she said.

Forecasts powered by supercomputers

The V3 study provides the region’s most advanced climate projections to date, with the ability to zero in on grid cells spanning 8km over Southeast Asia and 2km over Singapore using the CCRS’ customised Regional Climate Model from six selected Global Climate Models (GCMs). CCRS also engaged about 20 government agencies.

For context, GCMs like the IPCC AR6 typically have a spatial resolution of 150km and do not show the variations in climate change projections at a more localised level.

There have been efforts underway to downscale Global Climate Models such as the World Climate Research Programme’s Coordinated Regional Downscaling Experiment for the Southeast Asia Region (CORDEX-SEA), which the V3 study contributes to.

These finer climate projections were enabled by the new supercomputer the centre had procured in 2022 – the single biggest expense of the study – which is hosted at the country’s National Supercomputing Centre, said Aurel Moise, deputy director of the Department of Climate Research at CCRS.

The last study released eight years ago, also known as V2, relied on the UK Met Office’s Regional Climate Model and only provided climate projections with a resolution of 12km over a limited geographical domain.

Singapore will be sharing the V3 data with Asean member states at a later stage for adaptation planning, stated the joint media release.