Singapore’s central bank has become among the first in the world to define what counts as “transition” investments with its recently launched sustainable finance classification system, or taxonomy.

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

Unlike green finance, where funds are used by projects already considered “green”, transition finance is intended to help more carbon-intensive sectors become greener over time.

There is growing international consensus that financing transition activities, beyond green activities, should be high on the agenda for emerging markets that are still highly dependent on high-emitting sectors and relatively young coal fleets.

However, a lack of uniform standards has impeded financing flows towards transition-labelled investments, which remains a trickle in the global sustainable debt market, compared to green and sustainability-linked bonds.

“Most taxonomies define what is green and what is brown, leaving out the bulk of economic activities that are in-between,” said Ravi Menon, managing director of the Monetary Authority of Singapore (MAS) at the COP28 climate summit in Dubai, where the finalised taxonomy was launched.

Singapore’s guide for sustainable investments, dubbed the Singapore-Asia Taxonomy, seeks to fill this regulatory gap in transition finance for this region. Spanning eight sectors that account for 90 per cent of Asia’s emissions, it is among the most comprehensive taxonomies integrating transition considerations to date.

These are the eight focus sectors: energy, real estate, transportation, agriculture and forestry or land use, industrial, information and communication technology, waste and circular economy, as well as carbon capture and sequestration.

While it has been largely welcomed by market participants for overcoming key roadblocks that have slowed the growth of transition finance, some analysts have called into question the inclusion of natural gas as well as more nascent and expensive transition technologies like carbon capture, utilisation and storage (CCUS) in a purportedly science-based guidance.

In this article, Eco-Business looks at what counts as transition finance under Singapore’s new taxonomy, whether the rules can bring regulatory clarity to this emerging asset class and its implications for the sustainable debt market.

What counts as ‘transition’ investments?

The taxonomy adopts a “traffic light” system, which classifies economic activities, based on their level of alignment with environmental objectives, into green (near zero emissions), amber (transition) and red (ineligible activities).

The amber category represents transition activities that are not currently on a Paris Agreement-aligned pathway but are either moving towards the green category within a defined timeframe or bringing down emissions significantly by a fixed sunset date.

For instance, for an existing power plant to qualify for amber revenues, it must emit no more than 220 grams of carbon dioxide equivalent per kilowatt hour (gCO2e/kWh) by 2030. For the real estate and construction sector, building renovations that reduce emissions or energy consumption by 30 per cent by 2030 can be categorised as amber activities.

Unless otherwise stated, the amber category only applies to revenues generated from existing activities and infrastructure, not new projects. At the sunset date – generally set at 2030, with some exceptions for hard-to-abate industrial sectors – the amber activity will either get upgraded to a green activity or downgraded to an ineligible activity.

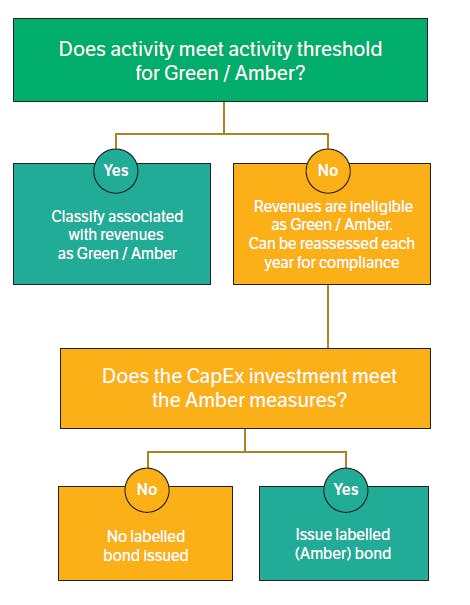

Unlike other taxonomies using a traffic light approach, the Singapore-Asia Taxonomy also adopts a measures-based approach. This allows for specific capital expenditure investments to qualify as amber or transition-labelled debt financing. Image: Singapore-Asia Taxonomy

However, if a project does not meet the amber activity threshold, capital expenditure (CapEx) investments – or money spent by a company to buy, maintain or improve a long-term physical asset – can still be eligible as amber use of proceeds if they meet other criteria under the “measures-based” approach that is unique to Singapore’s taxonomy.

Any investment that meets the measures criteria can issue a transition-labelled bond or loan.

For example, debt financing to retrofit a power plant with carbon capture and storage (CCS) technology can be considered a transition investment if it enables the facility to meet the green criteria (i.e. emit no more than 220 gCO2e/kWh) by 2035.

Ozgur Altun, associate director of sustainable finance from the trade body International Capital Market Association (ICMA), told Eco-Business that there is “perfect alignment” between the Singapore-Asia Taxonomy and ICMA’s Climate Transition Finance Handbook on the concept of transition finance, given that the taxonomy contains safeguards that go beyond the expressed commitment of an entity, through sunset dates and transition plans.

The only potential drawback of the taxonomy might be the perceived complexity of understanding it due to the mixture of different approaches, Altun said.

Contentious inclusion of natural gas

The Singapore-Asia Taxonomy recognises abated natural gas as a transition activity, as long as it aligns with the emissions thresholds of the global Transition Pathway Initiative’s 2°C-aligned scenario.

However, any inclusion of natural gas in a sustainable finance taxonomy runs the risk of “lock-in effects” of carbon-intensive assets or processes for the future, said Christina Ng, an independent energy finance analyst and member of the Science Based Targets initiative (SBTi) Financial Institution Net-Zero Expert Advisory Group.

While natural gas produces half as much carbon dioxide when burned compared to coal, climate scientists have discovered massive amounts of methane – a greenhouse gas with a warming effect about 84 times more powerful than carbon dioxide over a 20-year period – leaking from gas facilities across the world.

The taskforce acknowledged this point of contention, noting that Singapore’s approach “is not universally recommended in most jurisdictions where fossil fuel electricity generation will need to be phased out entirely to meet climate targets.”

Based on the taskforce’s assessment, gas power projects that rely on blending of low-carbon gas like hydrogen and carbon capture and storage (CCS) to reduce their emissions can qualify for transition finance, since these two levers are “technologically feasible” in the Singapore context.

However, it is currently unclear who might end up footing the cost of integrating CCS in the power sector. Ng’s analysis in March with the energy think tank Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis (IEEFA) found that the levelised cost of electricity with CCS usage is at least 1.5 to 2 times above current alternatives, which include renewable energy plus storage.

A similar addition of gas power plants into the EU Taxonomy, the green classification scheme at the centre of the European Union’s sustainable finance framework, led to heated debates and lawsuits earlier this year. Environmental groups argued that the move breached the EU’s climate commitments and a requirement for science-based policymaking.

Separate criteria for financing early coal phase-outs

The taxonomy stated that early coal phase-outs will not be classified using the traffic light system, but considered under a separate set of criteria since it constitutes a “transition away” from an emissions-intensive activity to a ready alternative, rather than a “transition within” an activity that will continue to be required beyond 2050. The amber category focuses on the latter.

On a facility level, a coal plant can be eligible for transition finance if it has reached a financial close before December 2021, has a positive asset value at the time of the proposed transition, has resulted in absolute emissions reductions from an early phase-out and retires at the latest by 2040 in developing economies, in line with the International Energy Agency (IEA)’s net zero pathway.

Beyond the facility level criteria to assess the ambition of phase-out projects, the taxonomy requires entity and system level commitments to not invest in new coal plants and be on a 1.5°C-aligned decarbonisation pathway.

Altun commended the taxonomy for requiring an entity-level transition plan, as relying on the traffic light approach alone would be “dangerous” and could result in perverse outcomes where coal plants might be able to obtain “green” or “amber” financing without continuously reducing their carbon emissions until the sunset date.

The criteria – which is consistent with global coal phase-out guidelines by the Glasgow Financial Alliance for Net Zero (GFANZ), Climate Bonds Initiative, Climate Policy Initiative and Rocky Mountain Institute – will be phased out from the taxonomy by 2035.

Implications on sustainable debt markets

It is especially important to rely on official sector guidance to bring legitimacy to transition-themed transactions and use of proceeds when it comes to transition finance, said ICMA’s managing director and head of sustainable finance Nicholas Pfaff.

ICMA updated its Climate Transition Finance Handbook earlier this year to include a list of official sector taxonomies and guidances for climate transition-themed bonds in the annex.

At this stage, it is hard to predict how taxonomies with transition elements might affect the issuances of transition-labelled instruments, which currently make up less than 1 per cent of the overall sustainable debt market, said Pfaff.

He noted that there has been a lot of experimentation in these instruments in Japan and China, which have both continued to back transition bonds despite divided market opinion.

In particular, Japan stands out for Pfaff given its plans to issue 20 trillion yen (US$ 136.2 billion) in sovereign transition bonds over the next decade. The country is reportedly set to issue 1.6 trillion yen (US$11 billion) worth of climate transition bonds in February next year.

“What we are hearing from some other Asian jurisdictions is if the Japanese experiment is successful, that will lead many other issuers to cross the line and experiment with issuances,” he said.

The international body is in the midst of gathering more data on the proportion of sustainability-linked bonds – which account for nearly 10 per cent of the sustainable bond market – related to transitioning hard-to-abate sectors, and is expected to publish its findings next January.

As of the time of the publication of the Singapore-Asia Taxonomy, there are no details available on how it will be applied or used. But the MAS has said that further information will be provided in due course about whether the taxonomy will be mandatory, if it will be used in disclosure guidance and debt financing, as well as the frequency of reporting against the taxonomy, if required.

More harmonisation or fragmentation?

To enhance interoperability with global taxonomies, MAS has commenced an exercise to map the Singapore-Asia Taxonomy to the International Platform for Sustainable Finance’s Common Ground Taxonomy (CGT) to facilitate cross-border financing flows, according to its press release.

The CGT currently covers the EU Taxonomy and China’s green taxonomy, known as the “Green Bond Endorsed Project Catalogue”.

These efforts to harmonise taxonomies are welcome, especially with the steady proliferation of taxonomies with transition elements, which could lead to investor and issuer fatigue and further regulatory fragmentation, said Melissa Cheok, associate director at Sustainable Fitch, a research division of the credit rating agency Fitch Group.

“We have observed a degree of frustration and confusion among stakeholders as to which taxonomy and regulatory developments are the most significant and which need to be immediately prioritised and addressed,” Cheok said, noting that there is the risk that they might choose to align with a taxonomy perceived to be less demanding.

For instance, the Asean Taxonomy and Singapore-Asia Taxonomy overlap in their inclusion of a coal phase-out criteria and the use of a traffic light classification system.

But as more Singapore-based financial institutions provide financing towards eligible projects in Southeast Asia, Cheok expects more corporates to seek alignment with the Singapore-Asia Taxonomy. “This should boost the adoption of the taxonomy as the main standard of reference, at least within the region,” she said.

SBTi’s Ng said that it is unsurprising that there is fragmentation in sustainable finance taxonomies today, given that they are developed with each specific market’s interests in mind.

“It is interesting, however, to see the MAS’ approach of trying to harmonise with the CGT after its taxonomy has been finalised. I’ll be keen to see how succesful this approach can be,” she said.