This story is part of our Decoding Sustainable Finance series, where we attempt to break down complex terminology surrounding the latest regulations and trends in sustainable finance.

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

Singapore’s central bank recently proposed the use of a novel class of carbon credits, called “transition credits”, as a new financing mechanism to hasten the early retirement of Asia’s nearly 2,000 coal-fired power plants (CFPPs) in a working paper jointly published with consulting giant McKinsey and Company.

Current initiatives to finance early coal phase-outs in the region have mainly used blended finance, where concessional capital, usually from governments, multilateral development banks or philanthropic investors, is mobilised to de-risk and attract more private capital. These include the Just Energy Transition Partnership (JETP) in Indonesia and Vietnam as well as the Asian Development Bank (ADB)’s Energy Transition Mechanism (ETM).

Despite these efforts, the first managed phase-out transaction has yet to be completed in Asia.

The potential to scale existing efforts has also been constrained by the heavy reliance on concessional capital, which is insufficient to mobilise the private capital needed to finance the closure of the large and relatively young CFPP fleets in Asia.

“Retiring a CFPP is inherently uneconomical,” said Leong Sing Chiong, deputy managing director, markets and development at the Monetary Authority of Singapore (MAS) during the paper’s launch event in September.

“To successfully retire CFPPs at scale, we need to find a way to close the economic gap and this requires significant financing,” he said. The industry estimates that at least US$500 billion is needed to decommission the region’s 5,000 or so power plant units with an average age below 15 years old.

All of these coal plants need to be shut down by 2040 to reach net zero by 2050, according to the International Energy Agency. This means that the industry needs to achieve the ability to phase out at least two CFPPs every week from now until 2040.

Eco-Business explains how carbon credits can make this loss-making endeavour more economically viable and the key concerns that must be addressed to get buy-in from investors.

What are ‘transition credits’?

“Transition credits” are a new class of carbon credits that can be generated from reductions in emissions when high-emitting assets like CFPPs are retired early and replaced with cleaner energy sources.

While the paper published by MAS and McKinsey noted that ideally, CFPPs would be replaced by renewables, technically any lower-emitting sources such as natural gas or ammonia and hydrogen co-firing could qualify, depending on which national and regional taxonomies project developers take reference from.

MAS and McKinsey stressed that to ensure transition credits are of “high integrity”, they must align to the Core Carbon Principles, a global benchmark for carbon credit quality by the governance body Integrity Council for the Voluntary Carbon Market (ICVCM).

For instance, the emissions reduction from high integrity credits must be “permanent”, meaning they are demonstrated to be irreversible. Some proposed guidelines include measures to ensure retired CFPPs are no longer used for generating power and their replacement with cleaner energy sources to minimise the need to restart the operations of retired CFPPs.

Reduction in emissions from the credits generated must also be sufficiently “additional”, meaning they only finance the early retirement of CFPPs which would not have closed early without the support of such a scheme. This excludes supporting old, inefficient and loss-making plants that would have shut down either way due to market forces or government mandates.

This additionality requirement could be fulfilled when host jurisdictions have no legislation mandating the early retirement of CFPPs or have not set emissions quotas for the sector under a carbon trading scheme before the announcement of an accelerated early retirement date – something that Indonesia launched earlier this February.

While MAS is currently exploring the use of transition credits in the context of early coal retirement transactions, they could potentially be used to finance the transition of other carbon-intensive sectors as well.

How can these credits incentivise early coal phase-out in Asia?

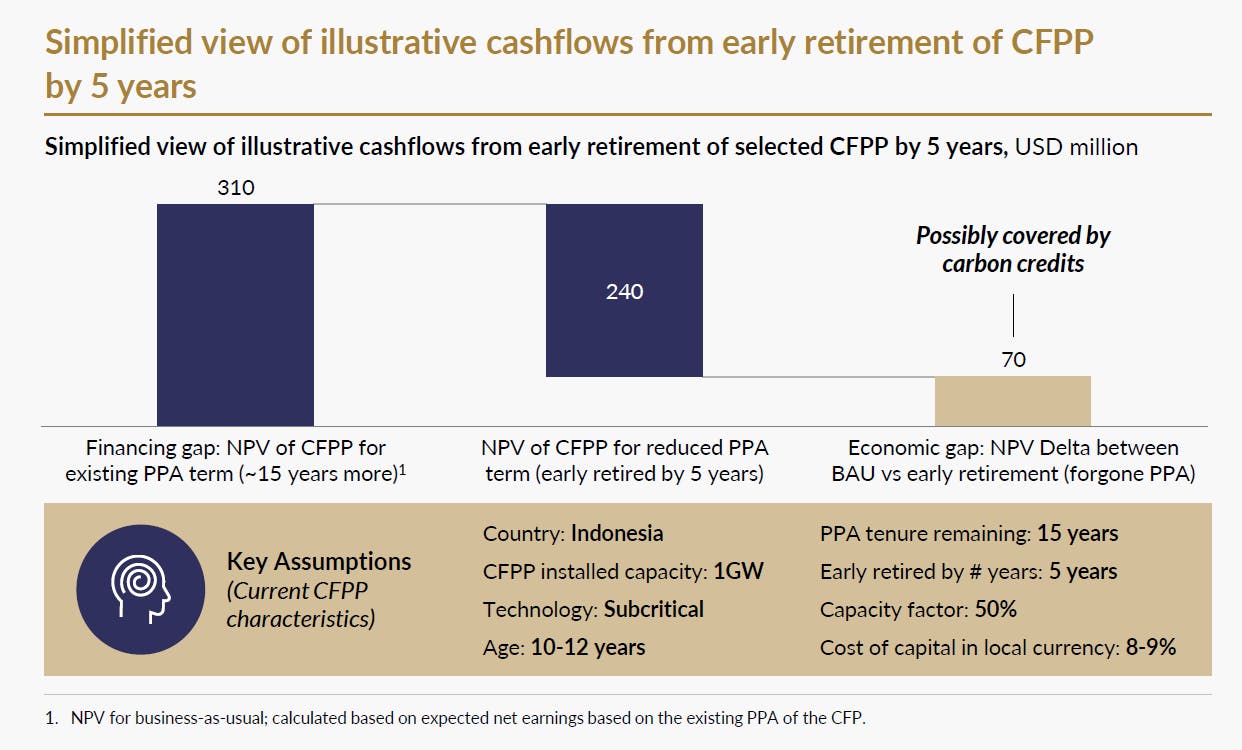

Based on the economic model developed by MAS and McKinsey, a plant in Indonesia with 15 years remaining on its power purchase agreement has a net present value of US$310 million.

If the coal plant is retired five years earlier, this value falls to US$240 million, resulting in an “economic gap” of US$70 million which investors will need to fill to break even.

This gap could possibly be covered by selling transition credits priced at about US$11 to US$12 per tonne of carbon dioxide equivalent, according to the model.

The economics of retiring a one-gigawatt Indonesian coal-fired power plant with 15 years remaining in its power purchase agreement, based on the cash flow model constructed to estimate the financing and economic gaps created by an early retirement of a plant. Source: MAS and McKinsey’s working paper

For context, Singapore-based carbon exchange Climate Impact X (CIX)’s June price assessment benchmarked nature-based avoidance credits issued between 2019 and 2022 at US$5.36 per tonne, while carbon prices in the European Union have gone past US$80 a tonne.

Is there an established standard for such credits?

So far, no there is no established standard for the issuance of transition credits.

But the development of methodologies for this new category of carbon credits are underway by certifier Gold Standard, carbon offset developer South Pole (under the Coal to Clean Initiative), non-profit Winrock (under the US Energy Transition Accelerator) and the World Bank.

“The development of methodologies will take time and understandably so, as these methodologies should be thoroughly scrutinised before being approved by reputable registries and standards setting bodies,” said Leong.

Avoidance credits, which represent verifiable emissions reductions through projects that prevent greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions from entering the atmosphere, have come under growing scrutiny of late. Compared to removal credits, where GHG emissions are directly removed from the atmosphere through nascent carbon capture technologies, avoidance credits face more difficulties in accurately measuring and quantifying avoided emissions.

An early look at the methodology Gold Standard proposed in April sheds some light on potential loopholes that need to be addressed for high integrity transition credits to be generated.

Carbon Market Watch acknowledged that the retirement of coal plants will be vital to decarbonise the real economy, but flagged issues around determining additionality in Gold Standard’s methodology, given the uncertainties in the energy market and the inability to precisely estimate the chances of CFPPs closing early without the support of carbon credits.

“The question is whether coal powered plants will become so uneconomical that market forces will ensure retirement on their own, or whether some financing through carbon credits will be necessary,” wrote the Belgium-based watchdog in its feedback.

Without being able to measure the future economic viability of CFPPs with certainty, it expressed scepticism about the suitability of carbon credits to incentivise the early retirement of coal plant and advised against their issuances.

“We’re not saying that it is impossible to finance some of the energy transition through credits, but it’s not a good idea to offset emissions with these,” said Gilles Dufrasne, global carbon markets lead at Carbon Market Watch.

What are some investor concerns?

While the inclusion of a managed coal phase-out in the Asean Taxonomy and the forthcoming Singapore-Asia Taxonomy has increased willingness among financial institutions to support the early retirement of CFPPs, the adoption of a new class of credits complicates this undertaking.

Eric Lim, chief sustainability officer, UOB, told Eco-Business that the success and wide-scale adoption of transition credits would be highly dependent on the integrity of the underlying early retirement projects.

This could be enabled by “a conducive environment with clear standards and guidelines, to provide the support for high quality decarbonisation plans upon which transition credits will be generated,” Lim said.

Helge Muenkel, CSO of DBS said that for this new asset class to effectively support the energy transition, it would “require new regulatory frameworks, as well as credible methods to measure and track emissions.”

Standard Chartered CSO Marisa Drew, who spoke on a panel at the paper’s launch, also raised concerns about permanence in transition credit projects, especially when the host jurisdiction has yet to commit to not having any new coal plants beyond what is already planned.

“The biggest fear we have around these credits is that you might shut something down over here. But if you don’t have a country-level policy that says when it’s shut, it’s really shut, we risk the integrity of this market,” said Drew.

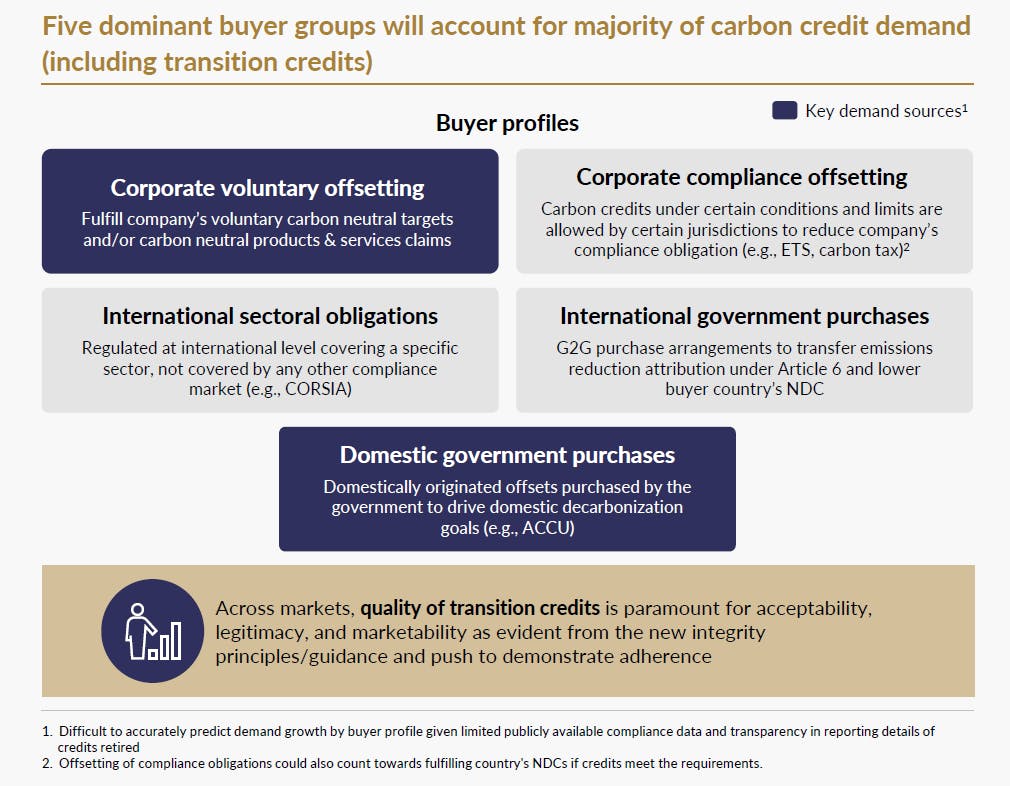

Investors will also be watching out expectantly for what transition credits can be used for. This is currently unclear, but the paper expects the demand for these credits to primarily driven by companies for voluntary offsetting to meet their climate targets and governments to drive domestic decarbonisation goals.

The report identified that demand for transition credits could come from five dominant buyer groups, primarily voluntary corporate offsets and domestic government purchases. Source: MAS and McKinsey’s working paper

In Singapore, transition credits could potentially be used for offsetting carbon tax liabilities. The city-state allows for emitters to use “high quality” international carbon credits included in Singapore’s whitelist to offset up to 5 per cent of their taxable emissions from 2024, when the country’s carbon tax increases to S$25 (US$18.20) from S$5 (US$3.60) presently.

While there is “great potential” for transition credits to be used for this purpose, MAS CSO Gillian Tan said that it is currently “premature” to use them for offsetting carbon tax liabilities in any jurisdication.

Tan revealed that MAS is currently working with the city-state’s National Climate Change Secretariat and the Ministry of Sustainability and the Environment to explore how transition credits can be recognised in its carbon credits whitelist.

“We’re going to look very closely at crediting methodologies when they do come out and explore whether these credits… can be eligible,” she said.

Another major concern is the potential time lag between funding the early retirement of a CFPP and the credit issuance, since the reduction in emissions needs to be verified. MAS’ Leong said that investors might need to wait for “ten or more years” for the credits to be issued.

This could deter buyers from making advanced commitments given that it opens them up to risks relating to changes in laws and policies and the possibility that the plant closure does not happen.

Leong suggested that some of the risks associated with the time lag in issuances could be reduced with innovative mechanisms that can facilitate early off-take, where a buyer agrees to purchase these credits before they are generated.

One such mechanism is advanced market commitments (AMC), where a group of reputable companies pledge to buy credits when they come to market without committing to any specific projects, which could support demand and diversify risks across a range of projects.

An example in the context of removal credits is Frontier, an AMC founded by global technology companies Alphabet, Meta, Shopify and Stripe, which has made a commitment to purchase US$1 billion of carbon removal credits between 2022 and 2030.

In the meantime, CIX is in the midst of carrying out a survey to size the demand for transition credits.

“Through that survey, we will get a better sense of what sort of pricing can be tolerated and how we can encourage that pool of off-takers to come to come up,” said Tan.

Will the revenues be used to fund a just transition?

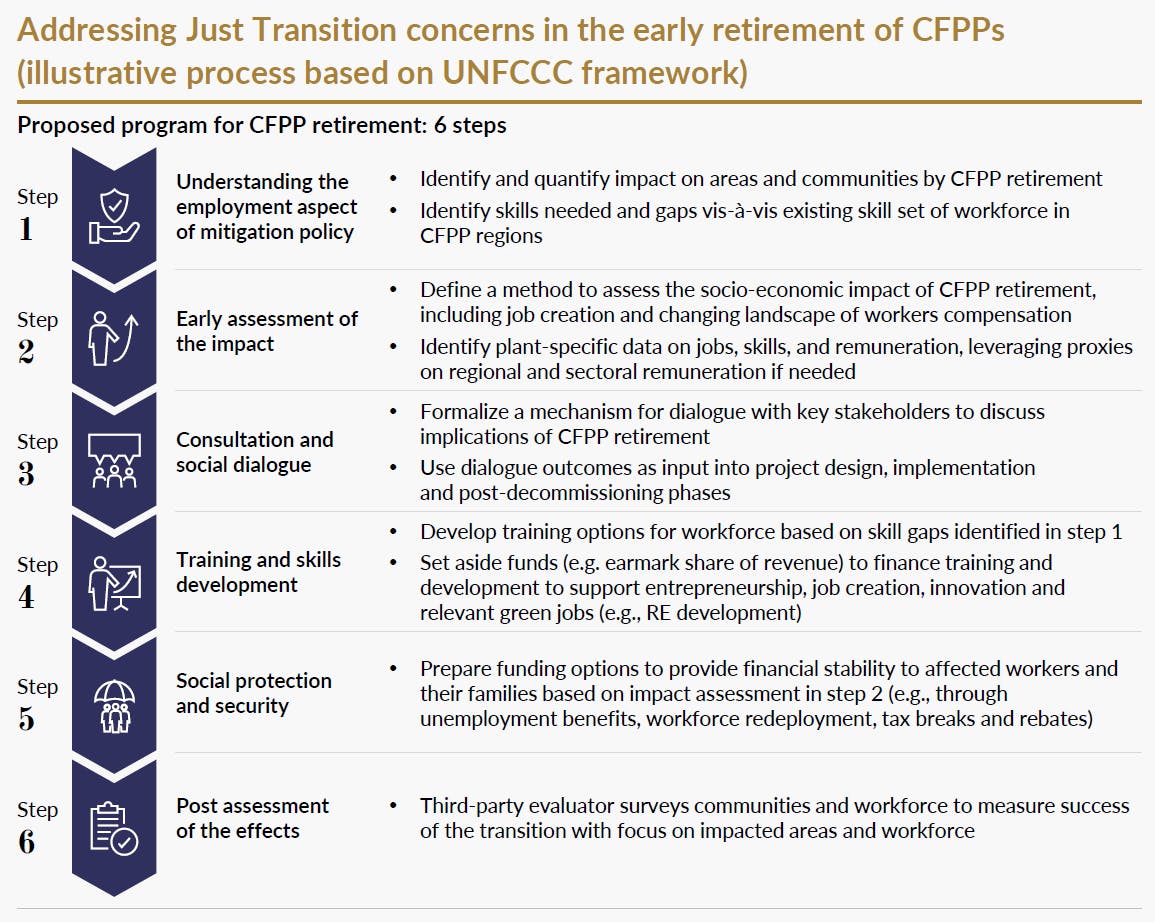

Apart from reducing the economic gap, the paper suggested that “a small portion of the revenue generated” from these credits would be used to finance activities that facilitate a just transition, including the compensation of affected workers and communities and retraining.

Proposed framework for addressing just transition principles when transitioning away from coal to cleaner energy sources. Source: MAS and McKinsey’s working paper

However, compared to the pricing mechanisms used in early retirement transactions, Tan foresees the just transition costs being harder to standardise. The cost considerations that have been reported in existing energy transition programmes have varied greatly so far.

“It’s really tough because I imagine the circumstances on the ground, depending on which geography and the sort of community, are quite bespoke and different. So that’s one challenge I think we will have to grapple with,” Tan said.

“Some of the pricing mechanisms can probably standardised fairly quickly. But for this piece, it will be interesting to see whether from Cirebon [a phase-out transaction in Indonesia that ADB is working on] and some of the other projects, we can actually extract some standardised principles that we can apply across the board, at least as a starting point.”