The oceans have long been regarded as a buffer against global warming as they store copious amounts of carbon dioxide in their vast blue depths and functions as one of the world’s largest carbon sinks.

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

But new research shows that having more CO₂ in the oceans could worsen climate change instead, as the waters near river mouths and coasts in turn leak more nitrous oxide (N₂O), a gas that is much more potent than CO₂ at heating the Earth.

The study, published in the Nature journal on Monday (13 March), highlights the complex processes that occur in response to man-made carbon emissions, and the risk of natural reactions that amplify existing negative impacts.

Researchers from the East China Normal University, Norwegian Institute for Water Research and the University of Texas at Austin bubbled small quantities of carbon dioxide through water samples collected a few kilometres off the coast of Shanghai, China, where the giant Yangtze River empties into the sea.

They recorded how the water increasingly turned acidic – a known reaction when CO₂ dissolves in water – and how that changed the amount of N₂O emitted from the samples. N₂O is over 300 times stronger than CO₂ in causing global warming, and can deplete the ozone layer that protects Earth from harmful solar radiation. The gas stays in the atmosphere for over 100 years.

Researchers bubbled carbon dioxide gas into water samples from the Yangtze estuary near Shanghai, China. The CO₂ gas caused both acidity and N₂O emissions from the samples to increase. Image: Nature/ Zhou et al.

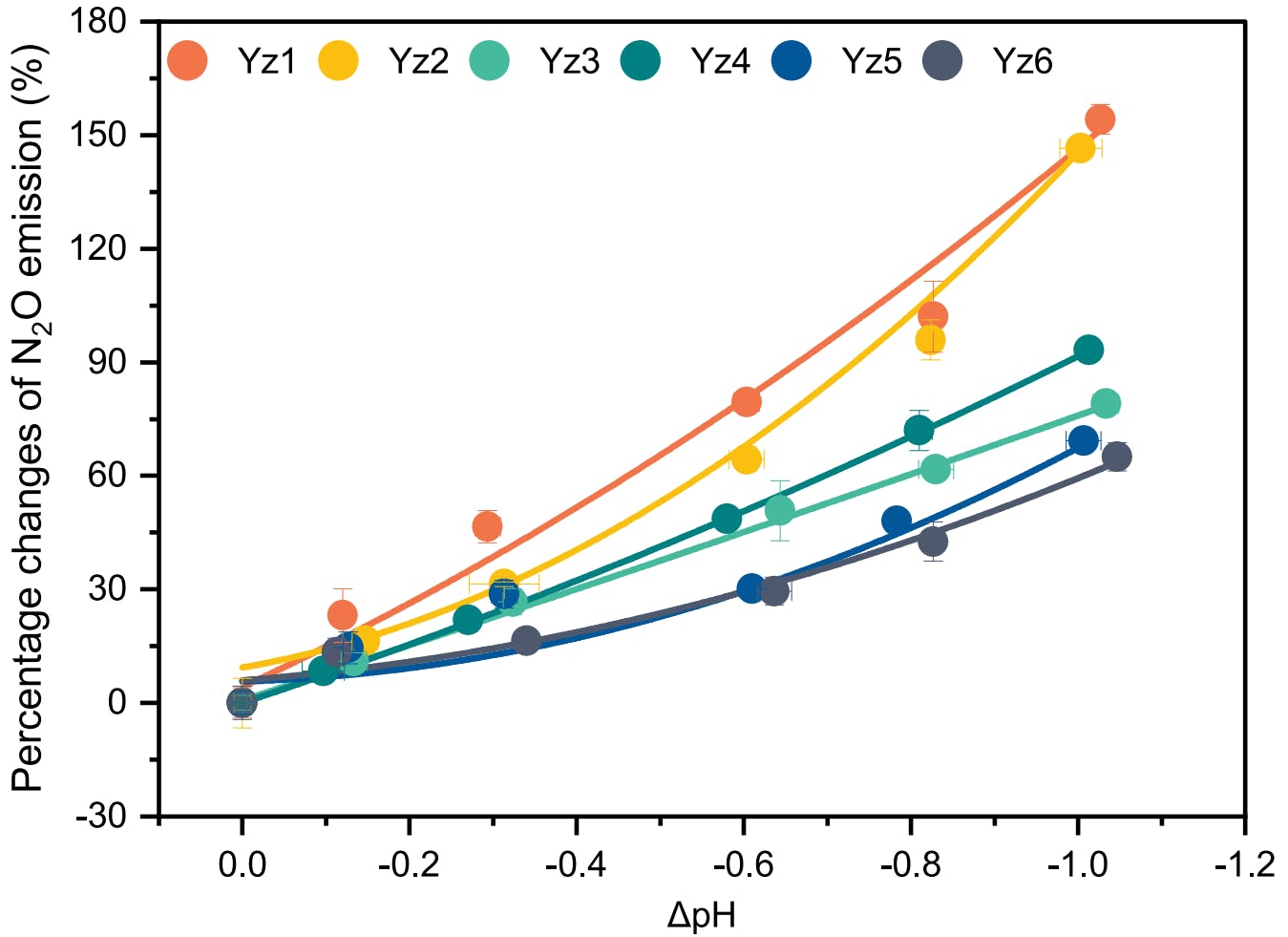

It was found that a small injection of CO₂, corresponding to a 0.1 unit drop in pH, causes an approximately 10 to 30 per cent increase in N₂O emissions. An increase in acidity corresponds to a lower value on the pH scale.

When pH dropped by 0.3 units – roughly equivalent to how much surface seawater globally are expected to acidify by the end of the century – N₂O emissions rose by up to 50 per cent.

At the extreme end, enough CO₂ to cause a full 1-unit drop in pH raised N₂O levels by between 60 to 150 per cent.

The researchers postulated that highly acidic environments could stress microbes and disrupt how they usually process nitrogen compounds for energy, resulting in elevated levels of N₂O by-product.

The phenomenon could be especially pronounced near estuaries, where the water gets its acidifying CO₂ content not only from the air, but also from episodes of algal blooms caused by chemical leaching upstream.

Should the results be applicable to estuarine and coastal ecosystems worldwide, and if such environments acidify in the future by about 0.2 pH units, the additional N₂O produced could account for some 2 per cent of the total amount each year generated by humans, the paper said. As it stands, existing research appears to rule out this trend in colder polar waters.

“These results provide important insights about the underlying mechanism of acidification affecting nitrification and associated N₂O emission, and we propose that further acidification in estuarine and coastal waters may alter [the] nitrogen cycle and accelerate global warming,” the study concluded.

Dr Zheng Yanling, a co-author and researcher at the East China Normal University, said a deeper understanding of such trends is crucial in predicting how coastal regions contribute to climate change, given the many impacts they face, which also includes coastal upwelling and complex biogeochemical processes.

Other environmental perturbations such as low oxygen levels and exposures to certain toxins can also contribute to increased N₂O production, Zheng explained.

No laughing matter

N₂O, colloquially known as “laughing gas” for its euphoric effect on people, is the third largest contributor to climate change by volume, at about 6 per cent of all greenhouse gases, behind methane and CO₂. A 2020 study found that N₂O emissions increased 30 per cent since the 1980s, contributed mainly by farms, factories and cars.

Emissions standards for vehicles and factories do exist for the nitrogen-based gas, but global attention and awareness is nowhere near its carbon-based counterparts.

Ambitious mitigation of N₂O emissions could save up to 10 per cent of the equivalent carbon budget in limiting global warming to 2 degrees Celsius, and offset ozone loss caused by old equipment like refrigerators, air conditioners and insulation foams, past research also found.