New research has identified that 18 per cent of China’s coal-fired power plants “can be retired first and rapidly” to help the nation achieve its goal of “carbon neutrality” by 2060.

The paper, published in Nature Communications, finds that 186 out of China’s 1,037 active coal plants are – from a technical, economic and environmental perspective – performing poorly and are “particularly suitable” for fast-track retirement.

The researchers say the prioritised shutdown could allow other existing plants to reach a minimum lifetime of 20 or 30 years – with gradually reduced operational capacity – under scenarios consistent with the 1.5C or “well-below” 2C temperature goals of the Paris Agreement, respectively.

The plan would see China phase out coal entirely by 2045 under the 1.5C scenario, or by 2055 under the 2C pathway, the study says.

However, the authors only explore the pathways without newly built coal-fired plants, which means China would need to stop constructing new facilities straight away for the plan to work.

Shutting the most inefficient plants

China has the world’s largest coal fleet and is home to the heaviest concentration of coal plants globally. The nation’s coal-fired capacity currently stands at around 1,050 gigawatts (GW) – half the global total – with another 250GW under development.

Since Chinese leader Xi Jinping set the goal for the nation to become carbon neutral by 2060 last September, the country’s central government has incorporated Xi’s climate pledges into many of its official blueprints. This includes the recently approved “outline” of the 14th five-year plan. (See Carbon Brief’s in-depth Q&A about the document’s importance and its implications for climate change.)

Just four days after the outline’s approval, Chinese state media reported that Xi had called for both the peaking of carbon emissions as well as carbon neutrality to be incorporated into the nation’s wider goals of building an “ecological civilisation”.

This is a concept raised by Xi in “Xi Jinping Thought”, a series of key ideas and policies derived from Xi’s speeches and writings. There is also Xi Jinping’s Thought of Ecological Civilization and Environment Sustainable Development instructing how to build what Xi calls a “beautiful China”.

The new study comes as Beijing is combining its carbon-reduction goals into the national agenda, but is yet to start drawing a plan for shutting coal-fired plants. On the contrary, some powerful interests in the country are pushing to build many more plants.

Dr Ryna Yiyun Cui, assistant research professor and China programme co-director at the Center for Global Sustainability of University of Maryland, is the paper’s lead author. Cui tells Carbon Brief:

“Rapidly shutting down the 18 per cent oldest, smallest and most inefficient plants opens up opportunities for improving air quality, human health, water security and other societal goals.”

Cui emphasises the need to immediately halt the construction of new coal-fired plants in China – one of the study’s key conclusions. She says:

“The sooner [a] ‘no-new-coal strategy’ is implemented, the more flexible the phase-out strategy can be for existing plants. Out of all the projects under development, I think a large portion is unlikely to proceed; while about 90GW already under construction are more likely to be implemented.”

Previous research by the China Electricity Council (CEC) shows China’s coal-fired units have operated for just 12 years so far, on average, and only 1.1 per cent of its units have operated for more than three decades, the typical lifespan of a coal-fired unit. This means that the Chinese coal fleet is much younger than those in the “western world” and harder to retire in a limited time without causing “substantial waste”, the CEC pointed out.

Prof Jiahai Yuan, a co-author of the new study and professor at the School of Economics and Management of North China Electric Power University, says the paper offers a vision of a decarbonised electric power system in China in the future. Yuan tells Carbon Brief:

“The biggest finding and discovery of this research is this: if China’s electric power industry uses the phase-out routes proposed by the paper in line with the 2C and 1.5C goals, there is every possibility for it to build a decarbonised electric power system to achieve the goals of a ‘beautiful China’ and carbon neutrality.”

He also highlights the importance of ensuring power reliability while phasing out coal in China – a view echoed by the study as its pathways weigh “multiple important national priorities”. Yuan adds:

“The exit of coal power is the inherent requirement and inevitable choice for [realising] the goal of carbon neutrality. However, as coal power is the most important ‘pillar’ source to China’s electric power system, its exit poses great challenges for electric power safety. How to phase out coal power [in an] orderly [manner] while ensuring the reliability of the electric power system is the key topic China needs to consider carefully.”

Identifying ‘low-hanging fruits’

With the help of an integrated assessment model – called the Global Change Analysis Model – and a self-developed metric, the study draws an action plan to help China gradually shutter its 1,037 active coal plants, which include nearly 3,000 units in total.

Cui notes the study’s data covers operating coal plants in China up to May 2019, primarily based on the Global Coal Plant Tracker (up to January 2019), with additional data collection to fill in the missing information. The research sample is different from the 2,225 power plants, which China’s upcoming national emissions trading scheme (ETS) is due to cover. Cui explains:

“Power plants covered by the national ETS also include other thermal plants, such as gas, oil, municipal solid waste, etc. It may also cover small coal units below 30MW [megawatts] that are not included in our data.”

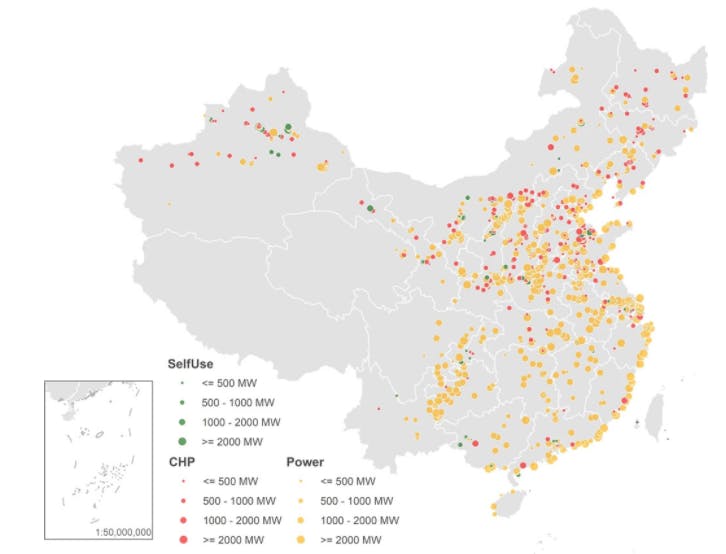

The map below, released as part of the study, shows the geographic distribution, size and application of all coal plants in this research. They fall under three categories: self-use or “captive” plants that primarily provide power to one customer, usually an industrial site (represented by green dots); combined-heat-and-power plants (represented by red dots); and power-only plants (represented by yellow dots).

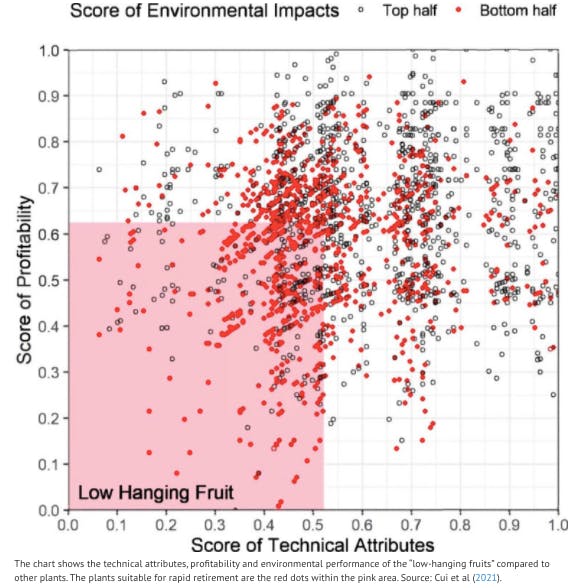

Through a scoring system covering eight different criteria under technical, economic and environmental dimensions, the researchers identify the coal plants that “can be retired first and rapidly”. Those facilities, accounting for 18 per cent of the entire sample, are referred to as “low-hanging fruits” – poorly performing units across all criteria with “relatively small share” of the provincial total coal capacity.

These plants have 111GW of installed coal capacity, or 11 per cent of China’s total, according to the paper. By shutting them, more than 800 plants with higher overall rankings would be able to pursue their designed lifespans – instead of closing prematurely. Under the 1.5C and 2C climate goals, the remaining plants’ expected minimum lifetime would be 20 and 30 years, respectively.

The study then sets out a detailed outline to guide the rest of the plants to retire one by one. Two retirement scenarios are proposed. The first scenario, “constant utilisation”, shuts the plants by their overall scores from low to high, but allows them to run at their current operating level. The second option, “guaranteed lifetime”, assures the plants have the aforementioned minimum lifespans, but requires them to reduce their working hours gradually.

Under the scheme, China would accomplish a complete phase-out of coal power by 2045 or 2055 to reach the 1.5C or 2C goal, respectively, the paper says.

Alvin Lin, China climate and energy policy director at the Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC), who is acknowledged in the paper as providing “helpful comments” to the research team, says the paper differs from others in its detailed plant-by-plant approach to phasing-out of coal power. He tells Carbon Brief:

“This is the first study to perform a plant-level analysis of coal plant retirement pathways for China, consistent with 1.5C and 2C global warming goals. It combines an analysis of each plant’s technical attributes, profitability and environmental impacts – CO2, air, water – to determine which plants should be retired first and which later, consistent with global warming goals.”

The geographical impact on coal plants

The paper finds that the identified “low-hanging fruits” have some common traits. It says:

“These plants often have been operating for more than 10 years, have a smaller unit size below 600MW and use the less efficient subcritical combustion technologies.”

In comparison, “large and more efficient” plants, as well as large CHP plants, perform better in the assessment. The study points out that “all of the most efficient ultra-supercritical plants (600MW and 1,000MW) receive an above-average score and will be the last to retire”. Ultra-supercritical plants are plants with higher thermal efficiency and, therefore, have lower carbon emissions per megawatt-hour.

The illustration below, published in the study, shows how the researchers identify “low-hanging fruits”. The red dots represent the bottom 50 per cent of the overall plants, as judged by their environmental scores. The bottom-left pink area symbolises the bottom half of the overall plants by their technical and profitability scores. The low-hanging fruit plants are indicated by the red dots within the pink area.

The paper says that the “low-hanging fruits” are mainly located in the north-eastern and central-eastern parts of China, with 60 per cent situated in six out of China’s 34 provincial-level regions: Shandong, Inner Mongolia, Henan, Hebei, Jiangsu and Shanxi. The map below shows these provinces’ location within China.

Moreover, more than 20 per cent of all existing coal capacity in provinces such as Hebei, Heilongjiang, Shanghai, and Shandong score poorly in the study and is suitable for prioritised retirement.

Explaining those regional implications, Cui says some could be attributed to “undesirable technical attributes”, such as the ageing plants located in China’s three north-eastern provinces, namely Heilongjiang, Jilin and Liaoning. She notes that health and water impacts may also cause differences, which can be seen in the municipality of Shanghai and the provinces of Shandong and Hebei. Cui adds:

“The share of low-hanging fruit plants do not vary significantly across provinces – which indicates that provinces with a large number of low-hanging fruit plants, such as Shandong, Inner Mongolia and Henan, also have a large number of coal plants.”

Geography also leads to different impacts on the estimated retirement timelines for the better-scoring coal-fired plants – those excluding the low-hanging fruits – under the “constant utilisation” and “guaranteed lifetime” scenarios.

On the national level, the latter route is expected to allow plants to retire around five years later than the former, until 2040 under the 1.5C climate goal, or until 2050 under the 2C goal.

On a regional scale, about half of the provinces show less than three years’ difference between the two pathways, while plants in a few other provinces see around a decade of delay in their shutdowns under the “guaranteed lifetime” model.

The variation is due to the fact that some of the newest plants, such as industrial self-use plants in Xinjiang and unprofitable plants in Gansu, are retired based on non-age-related grounds, the authors write.

The study finds the average operational lifetime for plants following the “constant utilisation” route is 18 years under the 1.5C goal, or 26 years under the 2C goal. In comparison, 82 per cent of the remaining plants will operate for 20 and 30 years at least with the “guaranteed lifetime” path under the 1.5C or 2C target, accordingly.

By contrast, plants following the “guaranteed lifetime” route will be expected to reduce their operating hours gradually.

The paper says that their annual operating hours will need to drop from today’s 4,350 hours to 3,750 hours in 2030, 2,500 hours in 2040 and below 1,000 hours in 2050 to meet the 2C climate goal. Under the 1.5C scenario, their projected yearly usage will be 2,640, 1,680 and zero hours in 2030, 2040, and 2045, respectively.

The researchers produced the map below to show the different retirement prospects for coal plants region-by-region under the “constant utilisation” scenario (solid line) and the “guaranteed lifetime” route (dashed line). The blue and green lines represent the projected pathways under the 1.5C and 2C scenarios, respectively.

Yuan links the regional contrast to the varying natural resources and different electricity load requirements across different areas. He tells Carbon Brief:

“To ensure the safety of electric power, while gradually phasing out fossil energy, [we] must clarify the regional positioning of coal power to realise the tiered exit of coal power in different regions. And this causes the discrepancy between different regions in the retirement timeline of coal power.”

Describing an ideal regional order, Yuan says that the phase-out of coal power should be prioritised in some areas of south-eastern and central China, where renewable energy is abundant. In the central-east, poorly performing small coal-fired units should retire first to optimise the units’ inventory, he advises:

“Considering that the coal-fired units in the north-western and north-eastern regions shoulder part of the heating responsibility, [the regions] should consider prioritising the exit of small cogeneration units with higher energy consumption. The task of supplying heating could be replaced by energy-efficient 300MW cogeneration units locally.”

He expects the plants in north-western and eastern China to be the last to shut down due to the two regions’ extensive inventories of coal-fired units and the “instability and uncertainty” of the wind power and solar output there.

The study carries the below graphic showing the distribution of operational lifetimes of coal-fired units under “constant utilisation” (yellow bars) and “guaranteed lifetime” (blue bars), with 1.5C (top panel) and 2C (bottom panel) as the goal, respectively.

Potential challenges

The starting point of the study is that China should stop building new coal plants. “China’s decarbonisation pathways suggest that any addition of new coal plants is not in line with the Paris climate goals,” the authors explain in the paper.

But this stipulation could prove challenging in reality. A recent report covered by Reuters says China now has 247GW of coal power under development – more than the entire US coal fleet.

Furthermore, Carbon Brief analysis from early last year reported that major Chinese power companies were lobbying for targets that would allow “hundreds” of new coal-fired power stations to be built. A separate study from last year said that China approved 20GW of installed coal power capacity between January and June in 2020 – a higher volume than the annual installed capacity of any of the previous four years.

Hong Miao, sustainable investment programme director and senior energy expert at the World Resources Institute (WRI) in China, who was not involved in the study, tells Carbon Brief there are challenges facing the phase-out of coal in China. Miao says there are a few critical factors driving the continued growth of coal power in China.

One is the increasing demand for electricity propelled by economic growth. “There is a consensus that, out of economic considerations, the demand for electricity will keep increasing,” Miao explains. She cites the construction of infrastructure, such as the high-speed railway network, as an example:

“So long as you want to build intercity rail transit, the electricity demand is bound to go up because the two go hand-in-hand.”

Another contributing factor is the traditional economic return the nation can expect by investing in coal power. “Normally, the investment in coal power could benefit the GDP two years down the line. And its construction cycle is stable,” Miao says. She adds that the fiscal advantage is compounded by the fact that China still sees robust investments in infrastructure.

The third determinant is the lack of relevant policy, Miao says:

“It is not yet clear what rewards would be given to those making the low-carbon transformation, or what restrictions high-carbon businesses would face – though such a reward and punishment system is currently being drawn up

Furthermore, the “developmental purposes” of China’s coal-based power sector increase these difficulties. Miao explains that “in the past couple of decades, the sector was born and developed as an adaptation to [China’s] abundance of coal on the one hand and its lack of natural gas and oil on the other”. She continues:

“The coal-based industry chain in some Chinese provinces has contributed to local economic growth and job creation over past decades. Before alternative technological applications get scaled up and become cost-effective, flexible services supporting high-penetration renewable energy are still needed. And coal power is currently the first option providing flexible services from an economic perspective.”

According to Yuan, the phase-out of coal-fired plants is an “inevitable requirement” of the low-carbon transformation for China’s electric power system, which – in turn – is the key to the nation’s realisation of peaking its emissions and achieving carbon neutrality. He explains:

“To coordinate the long-term goal of carbon neutrality and the short-term goal of ensuring electric power safety, the retirement of coal power must hold the overall safety of the electric power system and carbon emissions reduction as primary goals.”

However, “an orderly phase-out must be upheld”, he adds:

“If it’s too slow, the timing of the transformation would be missed and carbon neutrality would become more difficult. If it’s too quick, electricity could become unreliable, the price of electricity could surge, and large amounts of assets could be stranded.”

Referring to the new study, NRDC’s Alvin Lin regards it as “an important contribution” to understanding how coal plants should be phased out in the coming decades from the perspective of tackling rising emissions.

However, he adds, “as the study authors acknowledge, there is also a need to conduct analysis in future studies about what this coal plant phase-out means for grid stability”.

Lin notes two possible areas for further investigation. One is “how to have a more flexible grid that allows for renewables and, in China, nuclear power, to replace coal power and meet growing electricity demand in a reliable way”.

The other, he says, is “how to address the social and economic impacts from transitioning from coal mining and coal power to zero-carbon energy sources, which requires further discussion, agreement and policies at the local and industry level”.

This story was published with permission from Carbon Brief.