Countries and companies could soon begin extracting rare metals used in a range of consumer electronics from the seabed floor on an industrial scale – something that has not previously been allowed under international law.

A new paper, published in npj Ocean Sustainability, analyses the future potential overlap between key fisheries and deep-sea mining in a region of the Pacific Ocean that has been at the centre of the deep-sea mining debate.

The researchers find that three tuna populations are set to increase in this region by an average of 21 per cent by mid-century.

This could result in conflict between the extractive and fishery industries – with risk of “substantial” environmental and economic impacts, the study says.

The findings highlight the “huge number of unknowns” about the possible effects of deep-sea mining on ocean life, an expert who was not involved in the study tells Carbon Brief.

Deep-sea minerals

The deep seabed covers about two-thirds of the total ocean floor, according to the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN).

Spread across parts of the seabed are polymetallic nodules, which contain metals such as copper, nickel and cobalt.

These minerals are used in a range of items, including electric vehicle batteries, solar panels and touchscreens – and are expected to be in high demand in future as the transition to renewable energy continues.

Scraping these metals from the seabed is allowed for research purposes and, as of last month, countries can now technically apply for industrial-scale mining permits on the high seas.

“

With the twinned climate and biodiversity crises unfolding before our eyes, it is critical that we take a moment to consider whether we need a new industry.

Prof David Schoeman, ecologist, University of the Sunshine Coast

The International Seabed Authority (ISA), the UN body responsible for governing mineral and seafloor related activities on the high seas, is currently figuring out mining rules.

ISA discussions are ongoing, with countries split over the pace at which mining should begin. Delegates recently agreed on a new – but not legally binding – target to finalise the mining code by 2025.

Meanwhile, more than 700 ocean scientists and policy experts have signed a statement calling for a moratorium on seabed mining until more information is available on its marine impacts.

Prof David Schoeman, a quantitative ecologist at the University of the Sunshine Coast in Australia, who was not involved in the new study, says the findings show the “huge number of unknowns” around deep-sea mining. He tells Carbon Brief:

“I think that the major point being made here is that we are considering initiating mining operations in an environment that we don’t fully understand. This would be problematic if we could readily observe and understand associated impacts, so that the costs could be internalised by those making a profit. “

“But, in this instance, observation is near impossible, and legislative tools are complex and often at odds with each other.”

‘Complex and unknown’ interactions

Precious metals on the ocean floor are especially abundant in the Clarion-Clipperton Zone (CCZ), a 4.5m square kilometre (km2) region of the Pacific Ocean between Hawaii and Mexico.

So far, the ISA has issued 19 polymetallic nodule mining exploration contracts, 17 of which are located in the CCZ – covering around one-quarter of the zone’s total area.

To understand the wide-ranging impacts of deep-sea mining, the researchers look at projected tuna biomass increases in the CCZ region, with a buffer zone of 200km around the area.

They use previously published projections of climate impacts on the distribution and abundance of the three most commercially important Pacific tuna species – bigeye, skipjack and yellowfin.

They examine these changes under two emissions pathways: RCP8.5, a very-high-emissions scenario, and RCP4.5, a moderate-mitigation scenario.

The three tuna species are expected to increase by an average of 21 per cent in the CCZ area under both medium- and high-emissions pathways.

This suggests, the authors say, that tuna will move to this zone “regardless of the climate-change scenario”.

They add that the interactions between deep-sea mining, fish populations and climate change are “complex and unknown”.

But the projected increased overlap between eastern Pacific tuna fisheries and deep-sea mining areas could result in “increasing conflict” – alongside the other environmental and economic impacts in a “climate-altered ocean”.

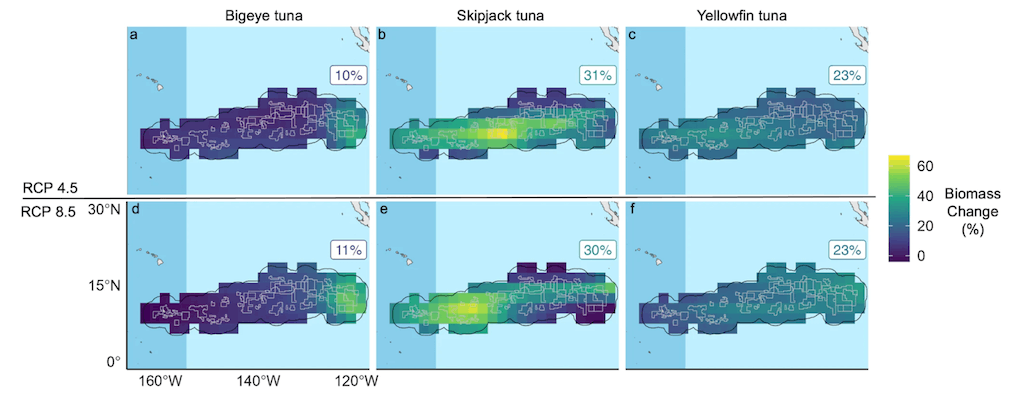

The charts below show the percentage change in the biomass of the three tuna species in the CCZ by the middle of the 21st century compared to recent years, for two emissions scenarios.

Percentage change in tuna biomass by the mid-21st century (average over 2044-53) relative to present (average over 2009-18) in the CCZ, under RCP4.5 (top) and RCP8.5 (bottom). Three species of tuna are included: bigeye, skipjack and yellowfin (left to right). Yellow colours indicate a higher percentage of biomass change; the percentages in each panel give the average increase for each species under each scenario. The black line around the CCZ marks 200km from deep-sea mining exploration contract-area boundaries. Source: Amon et al. (2023)

Dr Juliano Palacios Abrantes, a marine scientist at the University of British Columbia and a co-author of the study, says the work shows that “we actually have no idea what are the potential impacts between this completely new venture and these animals” in the ocean. He tells Carbon Brief:

“Nobody knows, because those studies have not been done…We tried to really focus on the management consequences… Nobody’s actually thinking of the possible interconnection of deep-sea mining and other activities.”

He says that tunas are “highly migratory” and their movement between habitats may cross paths with other industries. He adds:

“As things move around, you’re going to have this potential overlap with other industries in terms of, in this case, fishing, but also we will need to think more about conserving biodiversity, managing ocean resources, all of these different questions.

“Starting new industries, in this case, specifically deep-sea exploration, without taking into consideration this reshuffling could potentially harm not only the ecosystem, the species, but also associated issues.”

Schoeman, who is not involved in the study, says that he is “somewhat surprised” about the tuna biomass projections, given other research shows future decreases of marine life under climate change.

He adds that it would be “good to see the results updated” in future with more recent climate projections than the ones used in the study.

However, he tells Carbon Brief that the study conclusion “remains robust, because it refers mainly to the vast number of uncertainties involved, and to the need to resolve these before initiating a new – and potentially harmful extractive – industry in the deep ocean”.

Palacios Abrantes says that, because just a single ecosystem model is used, there is some “uncertainty” in the tuna biomass projections. But previous research has also shown the projected eastern movement of tuna in the Pacific

‘Increasing conflict’

As the CCZ has considerable deep-sea mining interest, the study says the increase in tuna there could risk “increasing conflict” between deep-sea miners and fishers.

And any impacts on tuna stocks could have knock-on economic effects for communities and countries that depend on tuna fishing, it adds.

The study notes that this region has “some of the most profitable fisheries in the world”. The tuna industry value for bigeye, skipjack and yellowfin in the CCZ area is around $5.5bn each year, the paper adds.

Prof Octavio Aburto, a marine biology professor at Scripps Institution of Oceanography, who was not involved in the research, says “discussions change” around emerging ocean issues once “big economic interests” realise the risks. He tells Carbon Brief:

“I think these topics are very important for discussion and opens the dialogues and the forums to start showing that there are a lot of conflicts that we need to solve very rapidly in order to really create more sustainable futures.”

However, he believes the findings could be “very useful” for fisheries to “start arguing that mining is a big issue and everybody needs to start regulating the mining”. He adds:

“But the fisheries themselves have been creating big issues – especially in the high seas – with a lot of illegal, unregulated and unmonitored fisheries”.

In a letter released alongside this study, groups representing the seafood industry are calling for a pause on deep-sea mining until there is a “clearer understanding” of the wider marine impacts.

Noise, lights and ship movement from deep-sea mining activities could all negatively impact fish in the CCZ, the study says.

Another issue concerning scientists are two plumes of sediment-laden water created in the deep-sea mining process. One plume is created when the minerals are dragged on the ocean floor, stirring up particles from the seabed.

Palacios Abrantes explains that this type of plume may not impact tuna, as it is likely to occur below the depth at which tuna usually swim.

The study co-author explains that a second plume is created after minerals are pulled from the seafloor to the ocean surface to be processed. The leftover material will likely be released back into sea, he adds, saying:

“Depending on where you release it, it could potentially affect the wildlife that live there. So, if you put it in the surface, it could affect tuna.”

Future decisions

The decades ahead “will herald a new seascape for ocean management”, the study says.

The authors raise questions about governance and transparency of the ISA and claim that the practicalities of monitoring and enforcing compliance with mining rules have “received little attention to date at the ISA”.

Dr Corinna Breusing, a marine research associate at the University of Rhode Island, tells Carbon Brief:

“[This study] highlights the complex interactions between climate change and deep-sea mining and their impacts on marine biodiversity and human society, especially communities in coastal and island regions.”

It emphasises the need for “more research on environmental impacts and solutions for effective management strategies before deep-sea mining should commence”, she adds.

Schoeman believes that more information on the “detailed ecology of the open ocean” is needed “before we contemplate new, potentially damaging activities like mining”. He tells Carbon Brief:

“With the twinned climate and biodiversity crises unfolding before our eyes, it is critical that we take a moment to consider whether we need a new industry.

“It may well be that we do. But if so, we should take another moment to ensure that the new industry bears the costs of its activities, rather than bequeathing those costs to nations that can least afford to bear them.”

This story was published with permission from Carbon Brief.