Southeast Asia is outpacing the world in its growing electricity demand but lagging in clean energy adoption, allowing cheap but pollutive coal to dominate the energy mix, putting net-zero emissions targets out of reach, according to a report published Thursday (7 July).

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

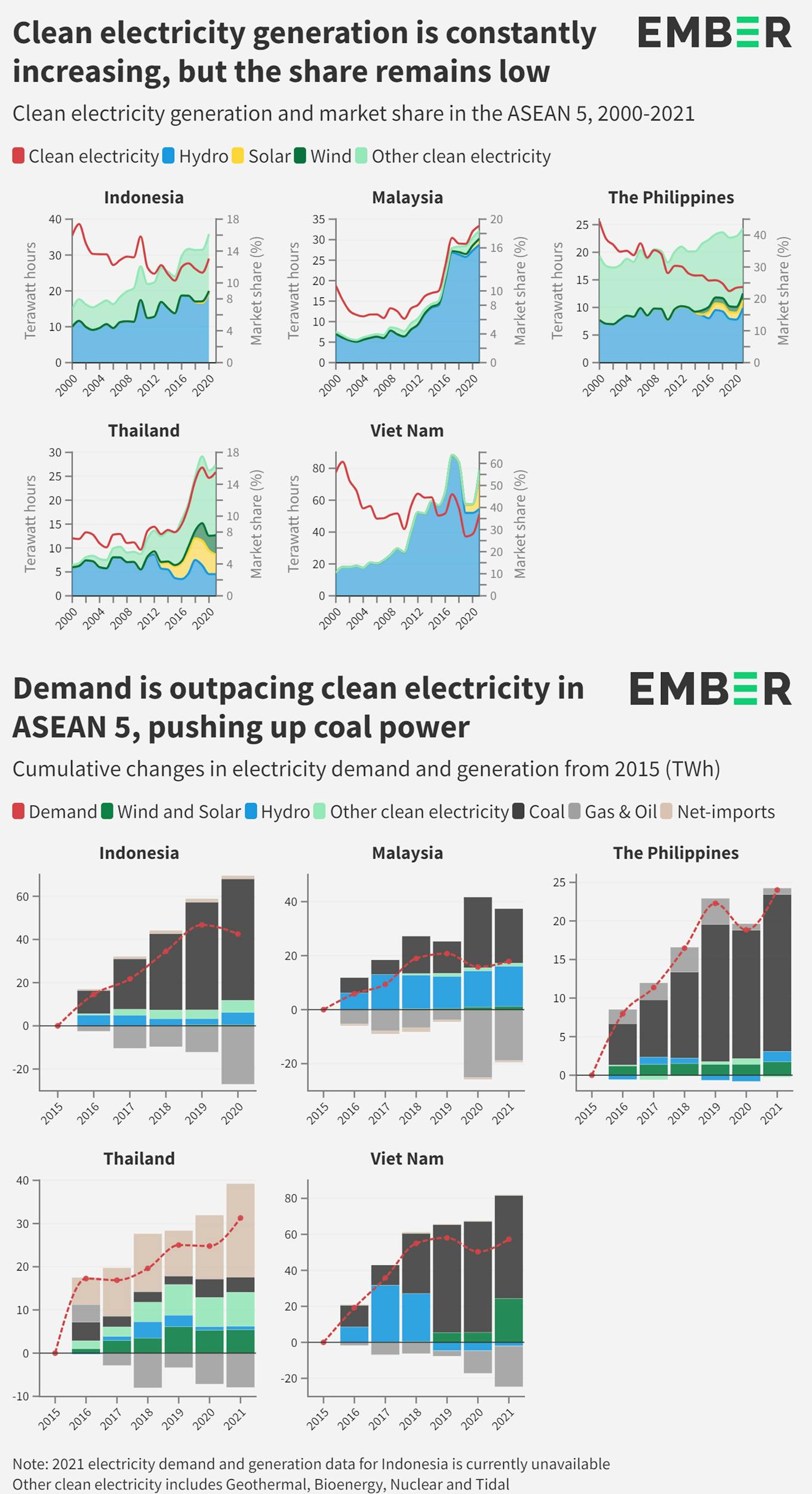

The need for electricity rose 22 per cent in the region from 2015 to 2021 — five percentage points higher than the world average — but this demand was met by only a 39 per cent increase in low-carbon power, said the study by London based non-profit Ember.

Solar and wind facilities contributed to only 4 per cent of power generated in Southeast Asia last year. More clean electricity came from hydropower, which is renewable but frequently harmful to local ecology and communities.

Existing plans will bump solar and wind power to only 11 per cent of the region’s electricity by 2030, the study added. The world average today is already over 10 per cent, and growing.

The world will need solar and wind to generate 40 per cent of its power by 2030 to get to net-zero carbon emissions by 2050, according to the International Energy Agency.

The United Nations’ Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change has also said that keeping climate change in check will require both a sharp increase in renewable power generation and a rapid phase-out of fossil fuels.

The Ember report examined energy trends in five Southeast Asia countries — Indonesia, Malaysia, Thailand, Vietnam and the Philippines — which accounts for nearly 90 per cent of energy generation in the regional bloc. Clean energy sources studied also include ocean waves, biomass, geothermal and nuclear power.

“Rapid scaling-up of solar and wind, and grid modernisation, are going to be crucial pieces of the puzzle to solve the climate crisis in this region,” said report co-author and Ember analyst Uni Lee.

Coal outshining renewables

Top: The market share of clean energy in Southeast Asia has been stagnating or dropping in some countries, as fossil fuels rise faster. Bottom: Much of the rise in the region’s electricity demand has been fulfilled by coal. Image: Ember. [click to enlarge]

The slow growth of clean energy is causing its market share to stagnate and even fall in some Southeast Asian countries, as coal plays an ever greater role in fuelling economic expansion. Power sector carbon emissions in the five studied countries rose 21 per cent in the last six years, the report said.

The biggest laggards are Indonesia and the Philippines, which saw their coal electricity generation increase by over 80 terawatt-hours since 2015, with small increases in clean energy output.

Both countries have been leveraging their large hydropower and geothermal potential for decades, but have struggled to make inroads with solar and wind power.

Even Vietnam, which is considered a success story in Southeast Asia due to its lofty solar and wind targets, saw its clean energy additions overtaken by coal in recent years.

Malaysia is a relative bright spot — with 93 per cent of its new electricity demand for the past six years met with hydropower. Coal use has risen sharply in the country, but it is counterbalanced by a drop in the use of oil and gas.

Thailand, meanwhile, has been relying on energy imports to fulfil its growing electricity demand. The country imports coal and hydropower from neighbouring Laos and Malaysia.

Greater ambition needed

Fossil fuels will continue to play an outsized role in the energy mix if governments do not scale-up their renewable energy plans, even as wind and solar energy prices undercut hydrocarbons, the report said.

Report co-author and Ember analyst Achmed Edianto told Eco-Business that states could pay for building transmission lines to woo private investment in renewable energy projects, especially in jurisdictions like Indonesia, Vietnam and Thailand, where the state-owned utility is the sole electricity buyer.

Analysts have said that building grids which can withstand the variable power supply from wind and solar power projects is key to scaling up their deployment. In past years, solar facilities in Vietnam had to reportedly dump up to 80 per cent of their output because the power lines then could not handle sudden mismatches between electricity supply and demand, causing the project owners to lose money.

Financing solutions would be more varied in open markets such as in the Philippines, Edianto added.

A recent Bain & Company report said that Southeast Asia countries may be underestimating the cost of the grid upgrades needed to scale-up renewable energy deployment. It suggested countries explore public-private financing options.

The Ember report said that multilateral cooperation would help better allocate energy resources and meet Southeast Asia’s energy demand, including for countries which are not major energy producers such as Singapore.

The Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) has been working on creating a unified power grid for 25 years. Last month, the project received a boost when Singapore started buying hydropower from Laos, with the electricity routed through Thailand and Malaysia. However, Malaysia and Indonesia have said they will not export renewable energy produced domestically.

“The region has to achieve its energy transition to achieve its climate goals, but states also have to maintain the sufficiency and reliability of their electricity supply. These are the core (issues) for the ASEAN region,” Edianto said.