An ambitious plan to export solar electricity from Australia’s Northern Territory to Singapore could transform the latter’s energy landscape—eroding the longstanding predominance of natural gas in its fuel mix—and be a model for other regions of the world.

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

The project by Singapore-based developer Sun Cable promises to be the world’s largest solar farm, with 22 million panels spread over 15,000 hectares near Tennant Creek in the Northern Territory. It could supply 20 per cent of Singapore’s electricity within a decade, Sun Cable told various media outlets last week.

The solar farm would generate 10 gigawatts of power and have battery storage. It will supply electricity to Darwin through overhead transmission lines and transmit three gigawatts to Singapore via a high-voltage direct current (HVDC) cable running nearly 4,000km beneath the sea, allowing Singapore and the Northern Territory to have a more diverse electricity supply, Sun Cable said.

Community consultation for the project will begin later this year, Sun Cable announced on its website.

Its chief executive David Griffin told The Straits Times the firm needs to raise capital for the A$20 billion project (US$14 billion) but was confident “there are deep pools of capital for long-term infrastructure assets”.

The project is significant on several levels, analysts told Eco-Business.

World’s longest sub-sea cable connection

If successful, it would be a model that could be applied in other regions of the world—renewable energy projects involving Australia and Indonesia, or Europe and Africa, for example, said David Dixon, a senior analyst on the renewables team of Rystad Energy, an independent energy research and business intelligence company.

Sun Cable’s plan to connect Singapore and the Australian outback via 3,800km of HVDC cables would result in the world’s longest sub-sea cable connection by far, noted Dr Thomas Reindl, deputy chief executive of the Solar Energy Research Institute of Singapore.

The longest distances today are mostly for inter-connecting countries in the North and East Sea in Europe, which are in the range of 500 to 600km, he said.

There are longer cable connections being planned or under construction, such as the EuroAsia Interconnector project in the East Mediterranean Sea, connecting Israel to Cyprus and Greece by way of a 1,518km sub-sea HVDC cable, he added.

Kickstarting renewables

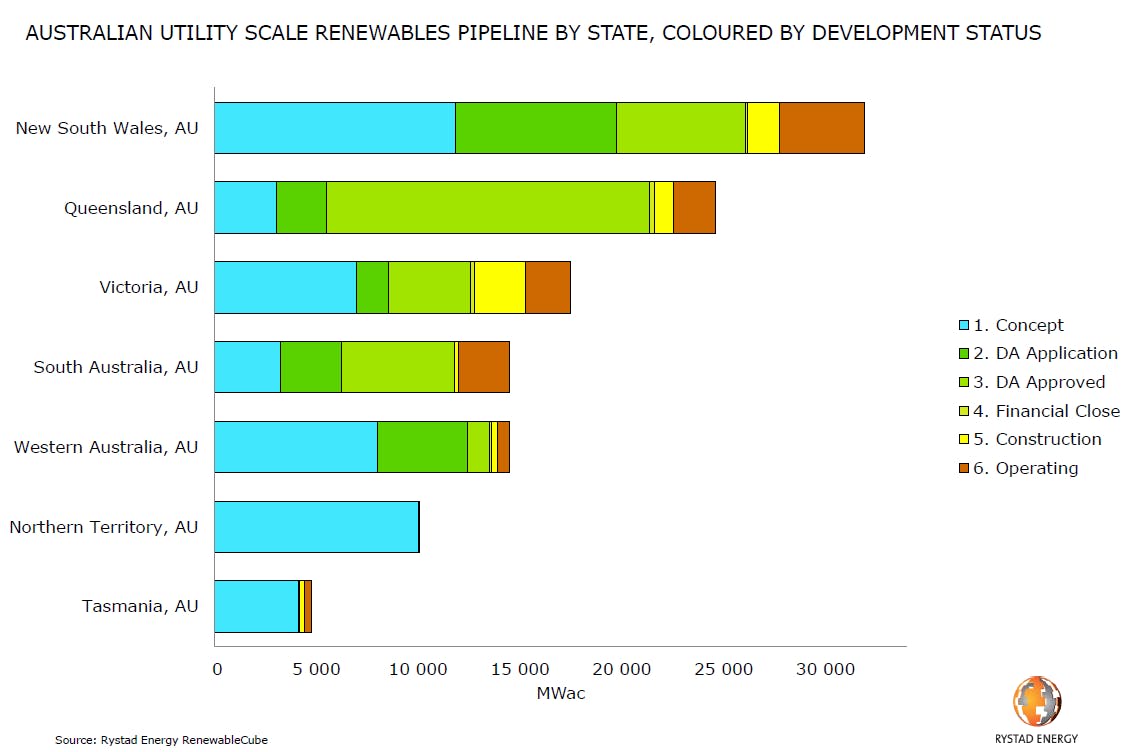

At the regional level, the project will kickstart the clean energy industry in the Northern Territory, the state with one of the lowest uptakes of renewables development in Australia, said Dixon.

The project represents tens of billions of dollars in investment and will create hundreds of jobs, he added.

The Northern Territory has one of the lowest uptakes of renewables development in Australia, as this chart, which takes into account Sun Cable’s project, shows. DA stands for development application. Image: Rystad Energy

For Singapore, the project would reduce the city-state’s heavy dependence on fossil fuels for electricity. Natural gas accounted for 95.2 per cent of Singapore’s fuel mix for electricity in 2017, according to the Singapore Energy Market Authority’s (EMA) 2018 energy statistics.

Coal formed 1.3 per cent of the fuel mix, petroleum products such as diesel and fuel oil made up 0.7 per cent, while sources such as solar, municipal waste and biomass accounted for 2.9 per cent.

Singapore used fuel oil to generate most of its electricity 20 years ago, but has switched mainly to natural gas which, according to the National Environment Agency, produces the least carbon emissions per unit of electricity generated amongst fossil fuel-fired power plants.

More than 70 per cent of the natural gas is piped in from Malaysia and Indonesia; the remainder is liquid natural gas which can be transported by ships.

Singapore open to new options

While Singapore has rapidly ramped up its installed capacity of solar—from about 59 megawatt-peak at the end of 2015 to 226.4 megawatt peak by the first quarter of 2019—and has been experimenting with renewable energy innovations such as floating solar panels, local deployment has hardly changed the country’s fuel mix. The land-scarce island still has the lowest renewable energy capacity of any country in the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (Asean), with the exception of oil-rich Brunei, according to 2018 data from the International Renewable Energy Agency.

Asked about the potential of Sun Cable’s project to supply one-fifth of Singapore’s electricity, the EMA would only say it is “open to new energy options to diversify our fuel mix and to be more environmentally sustainable”.

A spokesperson from the authority added: “Sun Cable has approached EMA and we will be meeting them to understand the details of their proposal.”

When contacted, Sun Cable told Eco-Business it would not be commenting further until its next funding round.

Challenges and rays of hope

Experts acknowledged the advantages of the project but said many details will need to be ironed out.

Due to higher and steadier sunlight levels in Australia, as well as economies of scale from large solar farms, it is cheaper to generate solar electricity there than in Singapore, said Christophe Inglin, managing director of Energetix, a company that designs and constructs solar photovoltaic systems in Southeast Asia.

The time difference between Australia and Singapore also helps, he said. With Australia being further east, its solar energy comes online a few hours before the sun rises in Singapore. “From a solar supply perspective, it’s like having a longer day with steadier sunshine,” said Inglin.

This raises the question, however, why the project developers are not first deploying such an HVDC link within Australia from its eastern areas to its west, which would be cheaper than going sub-sea and politically easier without having to cross borders, said Inglin.

Sun Cable told The Straits Times that it plans to explore integrating its Singapore cable into the Asean power grid.

While HVDC cables are the technology of choice to convey electricity over large distances—given the lower transmission losses compared to alternating current systems—a challenge is “staying intact across earthquake-prone zones” that lie between Singapore and Northern Territory, said Inglin.

Studies are limited on the environmental impact of submarine power cables.

More of such cables will be commissioned and installation may impact the marine environment through habitat loss, noise, chemical pollution, heat and electromagnetic field emissions, among other ways, a study published last year concluded. Its authors said overall impacts on ecosystems are considered minor or short-term but noted that uncertainties remain, particularly over the impact of electromagnetic fields which many animals such as sharks and turtles are sensitive to.

Ten years is probably the minimum timeframe needed for the project, said Reindl.

“This is obviously a very ambitious project and an implementation timeframe of a decade is probably the minimum one would need to consider, given the high hurdles in terms of detailed technical feasibility studies, contractual agreements between multiple parties…signing off-take agreements for (20 or more) years and obtaining financing, just to name a few,” he said.

And while the prospect of getting 20 per cent of its electricity supply from renewables is “tempting” for Singapore, issues to review include any interruption of supply and what a fair electricity market model for local generators and producers of solar electricity would be, said Reindl.

Challenges notwithstanding, Dixon said the project will boost Singapore’s energy security by reducing its exposure to the volatility of fuel prices.