The fastest way to slow down climate change may be to reduce methane emissions, says Fred Krupp, president of the Environmental Defense Fund.

While carbon dioxide usually finds itself centre stage in climate discussions, current methane emissions, he warns, will be responsible for more warming in the next decade than all carbon emissions combined.

“In 2023, it turns out that anthropogenic methane will actually warm the planet more than all the carbon dioxide, which comes from burning all the fossil fuels around the world,” said Krupp, referring to methane emissions that are a result of human activities.

Despite remaining in the atmosphere for a shorter time than carbon dioxide, methane is capable of trapping 80 times more infrared radiation from the sun due to its molecular structure. It is the second most abundant anthropogenic greenhouse gas after carbon dioxide and is responsible for about 25 per cent of global warming.

Along with agriculture, the production of oil, coal and natural gas are responsible for the largest share of human-made methane emissions.

Though methane poses greater near-term risks than carbon dioxide, it also presents a golden opportunity in the global fight against climate change.

Indeed, Krupp notes that any work to drive down methane emissions this year or next year will pay off immediately. “It is a big opportunity to reduce temperatures from what they otherwise would be,” he added.

“

Optimism is a prediction that it is all going to be okay. Hope is a verb with its sleeves rolled up. We have to be hopeful; we have to keep working on the climate problem.

Following heatwaves in North America, Europe and Asia, and July 2023 setting the record as the hottest month recorded on Earth so far, the harmful effects of methane can no longer be overlooked.

One organisation that is leading efforts on focusing global attention towards the importance of reducing methane emissions through its research and solutions is the Environmental Defense Fund (EDF), a United States-based non-profit environmental advocacy group.

Krupp, who holds a bachelor’s degree from Yale University and a law degree from the University of Michigan, has served as President of EDF since 1984. He joined at the age of 30 and fondly remembers the board chairman at the time questioning his suitability for the job during the interview because of his young age. “I told him if he did hire me, I promised I would do something about my age every day I was on the job,” quipped Krupp.

Throughout his almost 40-year tenure at EDF, Krupp has witnessed and fought for much change in the environmental space. One was reducing sulphur dioxide pollution, which causes acid rain. He recalls working alongside EDF and the United States Congress towards the start of his tenure to create an emissions trading system that would tax pollution and financially reward those who reduced their pollution. Since it was put in place in 1990, the system has reduced sulfur dioxide pollution by 90 per cent.

The development of emissions trading systems found in Europe today, some U.S states and China all came from initial work done by EDF on sulfur dioxide, said Krupp. “Within a couple of years, our then chief scientist, Michael Oppenheimer told me that climate change was going to be the biggest issue and many of the ideas we had on solving acid rain could be applied to climate change,” he said. “Almost everything we do now is [to address] climate change, whether it is reducing emissions or helping to thrive in the face of climate change.”

Today, EDF has over 3 million members and activists and more than 1,000 members of staff from different disciplines including scientists, economists, policy experts and lawyers. It has strategic partnerships in 30 countries and has offices across the United States and around the world including in London, Beijing and Jakarta.

While Krupp is proud of how EDF has grown over the past four decades, the issue of climate change has also become more apparent in that time. “We do not sit around feeling satisfied at all about the progress,” he said.

However, it is this same urgency that drives efforts and innovation within EDF, all with the intention of reducing methane emissions and slowing down climate change. “Optimism is a prediction that it is all going to be okay,” said Krupp. “Hope is a verb with its sleeves rolled up. We have to be hopeful; we have to keep working on the climate problem.”

In this interview with Eco-Business, Krupp talks about the biggest challenges he has faced, how Japan and South Korea play a key role in helping Southeast Asian countries reduce methane emissions and the importance of inspiring the youth to make a difference.

Since you took the helm at EDF in 1984, what are some of the biggest challenges you’ve faced in convincing companies, communities and governments to protect the environment?

One of the biggest challenges is to develop mutual respect and trust – you cannot work with people if they do not believe that you are honest and are going to treat them with respect. Another challenge was getting the proper buy-in from communities to do their part in protecting the environment. There are also vested interests in the status quo and people were understandably focused on other things like their jobs and family.

We understand that making a transition to a clean economy is a big undertaking and it is something new. But many years later we have seen the cost of wind and solar panels dramatically come down. I think more businesses are understanding that there are big opportunities for those who seize them, including opportunities to make a profit by undertaking this transition.

You attended the Energy Asia conference in Kuala Lumpur in June. Compared to other regions, what are some of the unique issues governments and companies in Asia face in cutting methane emissions, based on your observation from Energy Asia’s proceedings? How does EDF support their efforts?

The Asia Pacific region is poised to be the engine of global growth for years to come. But each country is at varying stages of development in the region, so each nation’s needs must be understood individually.

Several of these countries have very important national oil companies, and globally, these companies have been a bit behind their publicly-traded and privately-held counterparts in their commitments to reduce methane. Part of the reason for this is that these companies have a unique role as sources of revenue for their governments, while their governments have to meet a range of public needs, such as education and health care.

At the same time, Asian countries acknowledge the science that says they must reduce emissions. It is understandable that some governments are saying there is not a single pathway to achieving that goal [of reducing emissions]. The fastest pathway is by taking care of methane – a most potent pollutant.

We need fast pathways and low-emission energy systems for economic and sociopolitical stability. EDF will continue to communicate how delaying action will affect both the economy and climate, and in fact, people’s lives.

What work is EDF doing in Japan with regard to methane? How does this relate to EDF’s efforts in Southeast Asia?

Recently I was in Japan where EDF co-hosted with METI, the Japanese Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry, our second oil and gas workshop in Tokyo. It was attended by a number of senior officials and executives.

In Japan, as in many other places around the world, industry professionals and policymakers are fast gaining an understanding of the importance of oil and gas, and are increasingly aligned with the importance of reducing methane emissions.

I think more leaders in Japan acknowledge that the nation has a crucial role and responsibility to help Southeast Asian nations as they seek to reduce methane emissions.

Japan, as well as South Korea, have the potential to help drive supply chain improvements across the Asia Pacific region. Both Japan and South Korea import close to 100 per cent of their gas. They are two of the biggest importers [of gas] in the world and each country has an international portfolio of oil and gas projects that they are financing.

When I was in Kuala Lumpur [to attend the Energy Asia conference], the Asean Methane Leadership Programme was announced in Malaysia. This 18-month initiative, in which EDF is a key stakeholder, will focus on capacity building to help strengthen Asean companies’ plans, targets and financing options in reducing methane emissions.

In partnership with Malaysia, Japan can help reduce methane emissions. For instance, the Japan Organisation for Metals and Energy Security and Petronas recently announced that they are collaborating on methane abatement flagship projects which include methane quantification surveys, finding solutions to zero routine flaring and exploring the potential of establishing an electrification hub.

Tell us more about MethaneSAT, the methane-tracking satellite that EDF plans to launch. What role will it play in tracking methane emissions globally and how significant will its impact be in reducing methane emissions?

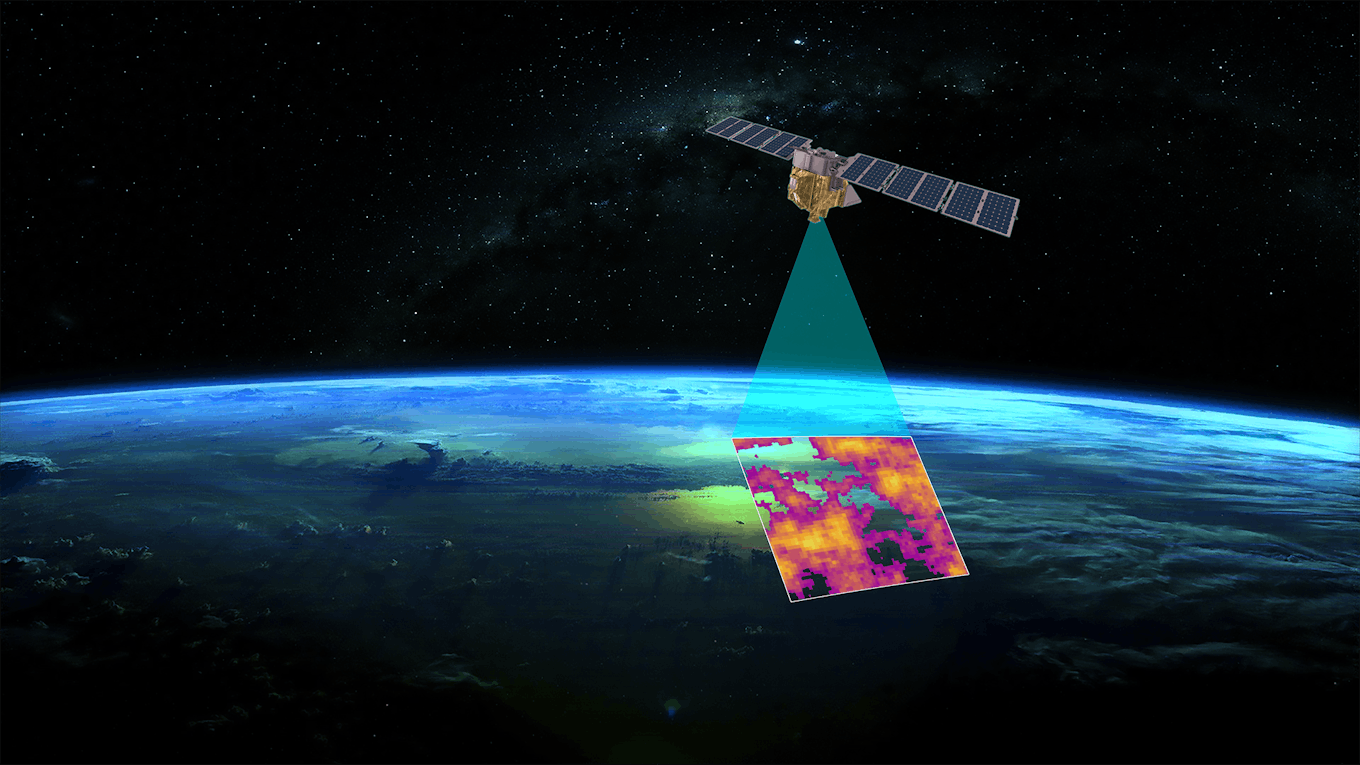

MethaneSAT is fundamentally different from what has come before from governments. It is a unique satellite with capabilities that we have developed for a unique purpose.

Its goal is to quantify methane emissions from the oil and gas industry worldwide and to do so with a wide field of view and with unprecedented precision. There is no other satellite in orbit, or one even planned, that is capable of detecting methane and quantifying the flows of pollution with both the scale and precision of MethaneSAT.

By releasing data, we can praise the good work of companies that are reducing their methane emissions and motivate those who perhaps have been slower to act and allow people everywhere to see and compare performance across operators and geographies and track that performance over time.

Because we are doing this privately, it is a faster process than government science. The satellite will provide us with transparent and actionable data, and we aim to make the data available to the industry, governments and citizens almost immediately after we collect it. I believe that gives the world the transparency to understand the facts in a way that will speed us towards a solution.

A computer-generated image of MethaneSAT in orbit, a satellite that EDF plans to launch in early 2024. It will be able to locate and measure methane emissions across the globe, providing crucial data that will help to enable methane reduction efforts. Image: Environmental Defense Fund

Unfortunately, [methane] emissions as they are currently reported around the world are often based on estimates. In the industry, this is called emissions factors. If the equipment is designed not to leak, the assumption is made that it is not leaking and therefore a very small amount of emissions is reported based on these estimates.

Recently there has been more work to empirically measure emissions in the United States and around the world. But often these measurements are sporadic and there has been little effort to have ongoing measurements; it is ongoing measurements that help you identify leaks that need to be fixed.

MethaneSAT uses a spectrometer that measures the amount of methane in the atmosphere. When light hits a methane molecule, it produces a unique signature that the spectrometer can quantify, enabling it to measure the concentration of methane present. By calculating wind direction, we can not only detect the concentrations of methane but also the source of it and how much is being emitted.

We expect MethaneSAT to be launched early next year. It will orbit the earth every 90 minutes and take multiple observations of 80 per cent of the world’s major oil and gas facilities every week.

How did you get interested in sustainability?

I have always enjoyed being outdoors and in nature, but my interest in sustainability began when I was in college at Yale. I had a professor who had this philosophy that we could solve problems if people would stop yelling at each other. That approach appealed to me. I decided that a great way to spend my time is to actually work on solving these problems and going beyond the rhetoric and shouting.

How does EDF help the youth of today feel empowered to fight for climate change?

Young people have the most at stake. In the United States, we have a group called Defend Our Future under EDF, which has over 80,000 members working to give young people the opportunity to work on climate change.

The most important thing I would say is [we give youth] hope. When people feel hopeless or helpless, they do not engage – whether it’s in their schools or with their employers – to constructively work to make progress.

But when they have hope and understand that they have an agency to make a difference, then they are more likely to be attuned to their opportunities to help. The fact that companies compete to hire the best employees and compete for the loyalty of their consumers means that more companies understand this key fact: that to gain the trust of this rising generation, they must do all they can to be a part of the solution to global warming.