DBS is the first Southeast Asian bank to update its coal policy to allow for the managed phase-out of coal-fired power plants, in line with the Singapore central bank’s direction outlined in a guidance document released last year, as it steers financial institutions to accelerate the retirement of the polluting plants.

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

At a briefing for the bank’s latest sustainability report on Tuesday, chief sustainability officer Helge Muenkel told journalists that DBS also remains committed to its 2019 pledge to cease new thermal coal financing.

In recent years, Asia’s top banks have come under increasing scrutiny for their continued fossil fuel financing. In its latest sustainability report, DBS updated that it has cut 33 per cent or about a third of its coal exposure across mining and power plants since 2021, the year it pledged to achieve zero thermal coal exposure by 2039 when the last of its remaining legally committed deals runs out.

At the end of 2023, the bank’s exposure to thermal coal was S$1.8 billion (US$1.3 billion), down from S$2.7 billion (US$2 billion) in 2021.

In 2023, the bank’s absolute financed emissions from its oil and gas portfolio declined by 10 per cent to 26.2 metric tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent (MtCO2e), compared to that in 2022, according to the report. This surpasses its interim target to bring down the sector’s emissions to 27.7 MtCO2e by the end of this decade. DBS attributed this decline to a deliberate reduction in business activities.

Muenkel stressed that the reduction in emissions “is not going to be [in] a straight line”, especially as demand for transition finance – that is, funding for carbon-intensive assets and activities to become greener over time – increases.

“There could potentially be steps back, where sometimes we are in a situation where emissions intensity goes up,” he cautioned.

The city-state’s regulator previously called for financial institutions to engage with, rather than divest away, from high-emitting entities to decarbonise their portfolios, and acknowledged that short-term increases in financed emissions are expected as a result.

Reducing exposure and financed emissions is “not the name of the game”, which is “real world decarbonisation”, said Muenkel, adding that DBS will continue to push for carbon reduction.

In a LinkedIn post published on Wednesday, Muenkel also elaborated on the importance of going beyond reduced coal exposure to manage the early phase-out of some 5,000 rather young coal power plants in Asia Pacific.

“We appreciate that there is some uneasiness about this,” he said. “It is complex, especially given the Asian context and the imperative is to do this in a just manner. But if we do not shut down these Asian coal power plants ahead of the end of their operating life, we won’t be able to meet the goals of the Paris Agreement.”

No consensus yet on emissions accounting

At the report briefing, Muenkel also responded to a question on whether the financing of early coal retirement would count towards the emissions intensity of its power portfolio in future reports, stating that DBS is in discussions with regulators and investors about the preferred approach for reporting the emerging category of emissions. It is a challenge, since “nobody has ever done it”, he added.

“I can’t answer this credibly right now because we haven’t agreed upon that. But whatever it’s going to be, it’s going to be very transparent,” he said.

Muenkel said that he is not opposed to carving out the emissions from financing early coal phase-outs as a separate category for reporting. “As the purpose is dramatically different, I wouldn’t mind having two buckets, where [we] understand how they are linked and nobody’s hiding anything.”

When asked about whether the bank’s coal policy will be updated to include captive coal, which refers to private coal plants that supply power exclusively to industrial facilities like nickel mines, aluminium smelters or steel plants, Muenkel told Eco-Business that it is an “interesting discussion” to follow.

At the moment, the bank’s exposure to captive coal is “very small” and “not material”, but DBS will likely consider the inclusion of captive coal “under strict conditions”, given that the smelters they power produce components that are critical for the energy transition, he said.

Indonesia’s new sustainable finance taxonomy, which was released last month, classifies financing of captive coal plants established up until 2030 as a “green” activity – a move that has drawn criticism from energy think tanks and environmental groups.

Steel and shipping miss targets

For now, DBS is on track to meet five out of the seven sectoral decarbonisation targets it set out in September 2022. These include: power, oil and gas, automotive, real estate and aviation.

Like the year before, steel and shipping fell short of their reference targets, though the emissions intensity for the steel sector came down compared to 2022, according to the bank’s sustainability report. It made progress in data coverage for the food and agriculture as well as chemicals sectors – two industries the bank has yet to set targets for.

“

[Meeting net-zero targets] is going to be a journey and the reality is it’s not going to be [in] a straight line… There could potentially be steps back, where sometimes we are in a situation where emissions intensity goes up.

Helge Muenkel, chief sustainability officer, DBS

On the reduced emissions intensity for steel, a hard-to-abate sector, DBS said that improvements were due to the use recycled scraps and new technologies, such as more efficient iron ore processing technologies. It plans to explore the use of carbon capture, utilisation and storage in the future.

But Muenkel observed that most clients in Asia, especially China, are still using a relative young fleet of blast furnaces rather than less pollutive electric arc furnaces, which are fed by scrap steel instead of raw iron ore, making the sector more challenging to decarbonise.

“There’s still a lot of work to be done, but it is also work that we cannot do alone,” he said. “If we were to move to electric arc furnaces, which are cleaner, you need more scrap metals, you need higher grade ore.”

The shipping sector continues to be the worst performer of the seven sectors DBS has set climate targets for. Muenkel flagged that this was due to the increased financing of shuttle tankers – specialised ships that transport crude oil from offshore oil fields to onshore refineries – through existing loan facilities they had committed to, prior to announcing its sectoral decarbonisation targets.

Sustainable financing in loan book growing

Using an updated methodology, DBS reported S$70 billion (US$52 billion) in sustainable financing loans, net repayments, as of end 2023, up from SG$51 billion (US$38 billion) the year before. These consist of green, renewables, sustainability-linked, transition, social and blue loans.

Besides an increase in absolute figures, Muenkel said that sustainable finance as a share of the total loan book has also grown, though he did not disclose the specific ratio it has gone up by.

Additionally, the bank facilitated S$18 billion (US$13 billion) in environmental, social and governance (ESG) bond issuances in 2023, down from S$24 billion (US$18 billion) the year before — a decline DBS ascribed to muted capital markets activity in the past year.

These transactions include the second tranche of sovereign green bonds issued by the Singapore government last September. The S$2.8 billion (US$2 billion) worth of bonds will be used to finance projects under its 2030 decarbonisation roadmap, including two new rail lines.

The bank’s joint venture in China also helped Hong Kong-based power company China Power to issue its first green panda bond to build wind and solar projects in Kazakhstan. Green panda bonds are Chinese yuan-denominated notes sold by foreign issuers to mainland investors, where proceeds are earmarked for overseas green projects.

Lim Wee Seng, group head of energy, renewables and infrastructure at DBS, who was also at the media briefing, added that the bank is increasingly partnering large corporations to provide technical support and financing solutions that address the “long-tail” Scope 3, or value chain, emissions from smaller suppliers.

Last year, the bank, alongside Swedish fashion retailer H&M Group, launched a collaborative financing tool to help Asian textile manufacturers access affordable capital to decarbonise their factories. It also worked with Hong Kong power giant CLP Power to provide subsidies for small and medium enterprises (SMEs) to buy renewable energy certificates (RECs).

Strengthened ESG due diligence process

Last month, DBS was called out by a campaign group for potentially supporting Indian conglomerate Adani’s coal expansion through a new bond deal it helped to arrange for the group’s renewables business. While Muenkel declined to comment on the US$409 million bond transaction, he reiterated that the bank’s ESG due diligence process for capital markets facilitation is “fairly robust”.

Earlier, when Eco-Business reached out for a response from the bank on whether Adani Green Energy’s close ties with other subsidiaries exposed to fossil fuels might come into conflict with its sustainability policies, DBS spokesperson also emphasised the presence of due diligence processes “to understand a customer’s approach to managing ESG issues”. The spokesperson declined to comment further on the green bond deal.

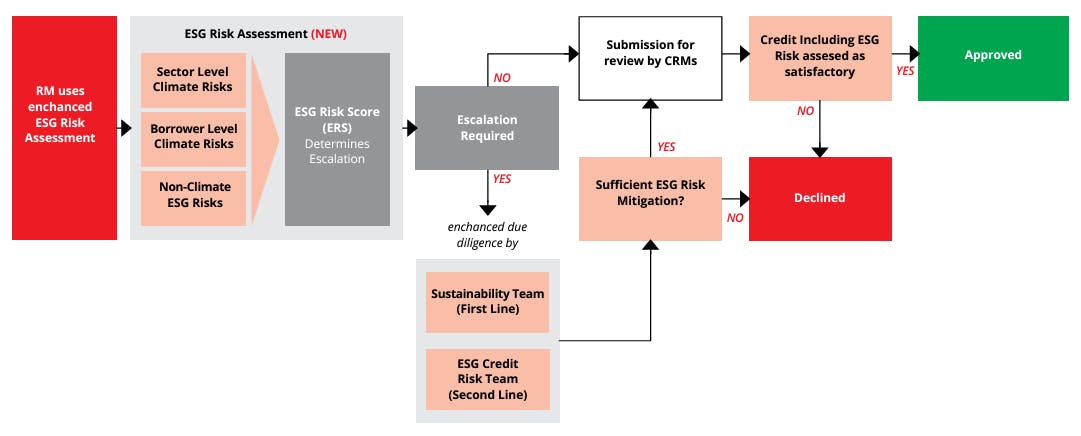

DBS now includes an enhanced ESG risk assessment within their credit application process. Image: DBS Sustainability Report 2023

The bank established a new ESG credit risk team, headed by HSBC veteran Anupam Jaiswal, to beef up its ESG risk assessment capabilities early last year. Since last July, new customers assessed to have higher ESG risk scores, based on their sector and borrower level climate risks and other non-climate risks, will be escalated for further due diligence. Factors that can contribute to higher risk scores include significant climate risks and the lack of human rights and modern slavery policies, said DBS.

“There is no way that somebody can game the system here and get something through without proper due diligence… we even report this all the way to the board,” said Muenkel.

He added that DBS is “one of the very few banks” that included emissions arising from capital markets transactions into its financed emissions. In fact, Muekel said that the bank’s accounting for such emissions is “more conservative” than industry standards as it reports 100 per cent of its share of emissions for a full year from helping to underwrite a bond issuance, for instance.

Currently, the industry-led carbon accounting standards body Partnership for Carbon Accounting Financials (PCAF) only requires financial institutions to report a third of these facilitated emissions, which critics have said lets banks off the hook for under-reporting their actual climate impact.

Correction note (6 March 2023): A previous version of the article stated that reduced emissions intensity for steel was achieved partly due to the use of carbon capture, utilisation and storage (CCUS) technologies. DBS has clarified that it is not yet financing CCUS projects in the steel sector, but might look to do so in the future. The article has been edited to reflect this.