[Editor’s note, 9 March 2023]: Read our latest analysis on ongoing industrial action against government plans to phase out traditional jeepneys.

A fleet of electric vehicles creeps into a gridlocked road in downtown Manila. They have no stainless steel horses on their hoods, or kitschy designs adorning their chassis. More noticeably, they are quiet and emit no fumes.

These new vehicles run purely on electricity supplied by rechargeable automotive batteries. Although they more closely resemble mini-buses, they are called electric jeepneys: eco-friendly versions of an iconic mode of public transport that has chugged on the Philippines’ roads since the 1950s, when American military vehicles left over from World War II were upcycled into hybrids of buses and jeeps.

E-jeepneys may not look or sound like their colourful predecessors, but by 2020 they could be the new kings of the road.

Colourful electric jeepneys in Makati City. E-jeeps have been in use since 2008 in the central business district, albeit with limitations to battery capacity. Image: Greenpeace

In 2017, President Rodrigo Duterte threatened to arrest anyone who went against the public utility vehicle (PUV) modernisation plan, which aims to replace public transport vehicles aged 15 years or older with modern vehicles that meet low-emission Euro 4 standards—or produce no emissions at all, like e-jeepneys.

The PUV plan is part of a wider push to provide a safer transport system for commuters and curb air pollution, and could be the beginning of a clean energy revolution on the congested roads of the archipelago.

But it also could mean the loss of livelihood for jeepney drivers and operators and the end of an era for a Filipino cutural symbol.

Newer, cleaner, but also pricier

While jeepneys are the Philippines’ most popular mode of transport, they are a major source of air pollution and traffic in urban areas like Metro Manila, which is Asia’s third most congested city.

International non-government organisation Clean Air Asia showed in a 2015 study that jeepneys, most of which are fitted with engines reliant on high-emission diesel, emit 15,492 tonnes of particulate matter pollution per year, accounting for almost half of all the particulate pollution in Metro Manila.

Jeepneys also face safety issues. The 70-year old vehicles are made from scavenged parts, have no doors, and only bar handles to keep passengers secure, and are prone to accidents.They are also a popular target for snatch-thieves.

“

[The government] says it is for environmental reasons. But I think the real reason is that the big operators, mostly backed by politicians, want to monopolise the industry.

Ed Sarao, owner, Sarao Motors

Jeepneys have survived for a generation because they provide accessible, cheap transportation at about 18 US cents per ride, compared to buses and trains, which cost abou 23 US cents and do not take commuters straight to their doorsteps.

The families of drivers, operators, mechanics and “barkers,” who call out the jeepneys’ routes to commuters, all depend on the iconic vehicles for their livelhoods. There are at least 118,000 families relying on the 54,843 jeepneys plying 685 routes in Metro Manila alone.

Transport groups representing jeepney operators and drivers have strong political clout, especially in urban areas that use jeepneys as a major mode of public transport. A jeepney strike can paralyse business operations in a city.

With transport groups holding strikes ever since the announcement of the PUV plan, the scheme has been slow to take off.

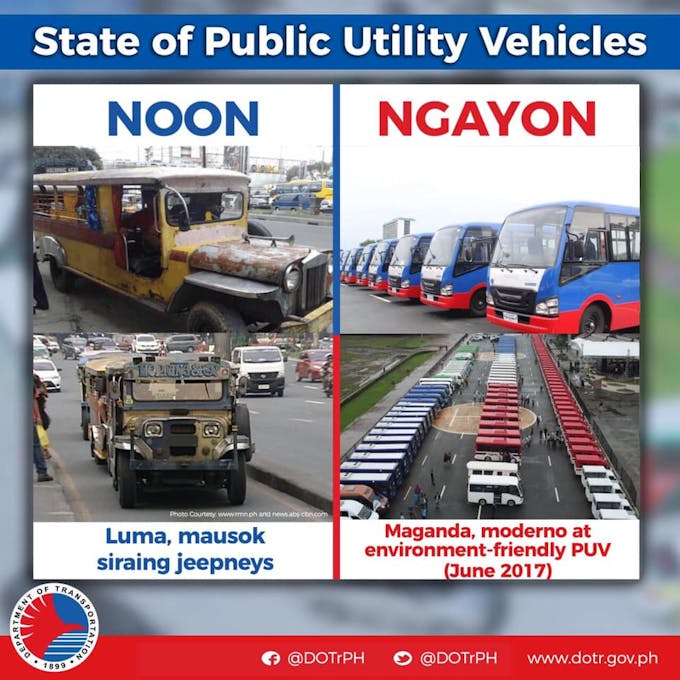

Then and now. A government advertisement promoting the modernisation programme shows how commuters could transition from old, smoke-belching jeepneys to modern and environment-friendlier transport. Image: Department of Transportation

The Land Transportation Franchising and Regulatory Board (LTFRB), an agency under the department of transport, has given operators until 1 July 2020 to phase out their old jeepneys.

Under the programme, the new jeepneys must also have enough room in the vehicle to accommodate people with disabilities and senior citizens, along with safety and convenience features such as GPS and CCTV cameras to deter robbers.

The modern jeepney will cost at least P1.2 million (US$23,400), for one vehicle. However, under the new guidelines, operators are not allowed to have just one unit; they must run at least 10. Operators must also demonstrate that they are a profitable, and must be a legal entity to secure funding from banks.

The additional costs of the new requirements have triggered an outcry among drivers and operators.

Ed Sarao of Sarao Motors, whose family was among the pioneers of the conversion of US military jeeps into passenger vehicles, said the PUV plan is a political move rather than a genuine attempt to improve public transport in the Philippines.

“[The government] says it is doing this for environmental reasons. But I think the real reason is that the big operators, mostly backed by politicians, want to monopolise the industry. They’re the only ones who can afford to buy the vehicles,” Sarao told Eco-Business.

Sarao Motors’ prototype of an electric jeepney has kept the look of the traditional vehicle to cater for commuters who prefer the iconic design. Sarao also offers a standard “lunchbox” model, which is simpler and cheaper to mass produce. Image: Eco-Business

The government has earmarked ₱2.2 billion (US$43 million) for the transport modernisation plan. The funds will be used to provide subsidies to drivers and operators to buy electronic jeepneys.

The government will be subsidising a maximum of ₱80,000 (US$1,500) per vehicle. However, that amount is only about 5 per cent of the total price, and would barely affect the monthly repayments of ₱21,000 (US$405). The loan for the balance will be at 6 per cent interest over seven years.

More support for the programme has come through a partnership with the Development Bank of the Philippines for a ₱1.5 billion (US$29 million) loan facility and Land Bank of the Philippines for a ₱1 billion (US$19.5 million) financing scheme to help cooperatives buy new jeepneys.

Tariff rates for e-vehicle components have also been reduced to zero, allowing e-vehicle manufacturers to import components at a more affordable price.

An Australia-based solar company called Star 8 Green Technology Corp has entered the local automotive scene, offering the use of its electric and solar-powered jeepneys to operators with no downpayments.

Solar panels on the roof of e-jeepneys. Image: Star 8

Star 8 has a fleet of 500 solar-roofed electric jeepneys. One unit costs ₱2 million (US$38,600) and has the capacity to travel approximately 100km on a full battery charge, with an additional 15km from the solar power produced during the day.

Ernesto Saw Jr, an operator and chairman of South Metro Transport Cooperative, said even a cooperative like his cannot afford to buy the e-jeepneys on its own. But he struck a deal with Star 8, which allowed his cooperative of eight jeepney drivers to use a fleet of vehicles at no cost until their loan got approved.

Manufacturers like Star 8 are preparing for the jeepney phase-out not just by helping operators ease into the programme, but also commuters by trialling a Grab-style app for passengers to book rides in advance. The Sakay.ph site, a Manila-based web service that helps commuters navigate their way around the city, already offers e-jeeps on its routes. Comet, another e-jeep manufacturer, has partnered with Sakay.ph to provide directions and routes for e-jeeps.

No more boundary system

Apart from the higher cost of the e-jeepneys, the modernisation programme will introduce a new employment structure where the income of jeepney drivers is standardised. Drivers will receive a mimimum wage and employment benefits such as overtime pay, social security, housing and healthcare insurance. Drivers have set work hours, replacing the “boundary system”, which enables drivers to rent jeepneys from operators.

Rudy Escala, 48, has been driving a jeepney for 30 years and opposes the new scheme. Like most regular jeepney drivers, he pays a boundary fee to an operator of US$15 a day. On a good day, he earns US$40, and is on the road by 5am, returning the jeepney by 9pm. At the end of the day, he usually takes home around US$25.

A daily income of US$25 for two months may cover the subsidy of an e-jeepney, but would leave nothing for himself and his four children, he said.

“I also don’t like the idea of having fixed hours because I won’t earn as much. When I have my own time, I can dictate how much I make every day,” Escala said.

27-year old Richard Salera, who has been driving an electric jeepney for four months, said he is able to save more money now than he could driving a traditional jeepney.

An automated fare collection system is one of the requirements of the PUV scheme, so that passengers no longer have to manually pass change to the jeepney driver. Image: Eco-Business

“Before I was used to taking home money every day, but I was not able to save. I was always tempted to spend every day because I had cash in hand. Now, I have learned to budget because I have to wait for my salary,” Salera told Eco-Business.

Salera added that the employee benefits have improved life for him and his family.

“Once, my mother got a stroke. I regret not being able to help with the hospital bills because I had no health insurance,” he said.

The vacation and sick leave he is entitled to now has made him more at ease as he does not lose income from taking time off.

“Now that I can save, I want to build my own house for my family. The benefits I get from driving an electric jeepney have really helped,” he said.

Standing room inside an electric jeepney. Image: Eco-Business

What do commuters think?

Norilyn Canete, 28, commutes to work as a sales clerk in a mall in Muntinlupa City. She said she prefers the quiet, clean new jeepneys but regrets that there are still too few of them.

“Every day I wait for the electric jeepney to arrive. But if it takes too long, I just ride the ordinary jeeps, which are more prevalent,” Canete told Eco-Business. “I prefer the e-jeeps because they have electric fans to keep the cabin cool, and the seats are more comfortable.”

Senior citizens like Joseph Gagate, 60, are among those who benefit the most from the roomier electric jeeps as he no longer has to stoop to get inside.

“

It will be nice to have some of the old jeepneys around, but maybe just in tourist areas. On everyday routes, their time has passed.

Ernesto Saw, Jr., chairman, South Metro Transport Cooperative

“I usually feel dizzy inside jeepneys because of the heat, but now that it’s cooler, with more space, I can relax,” Gagate said.

Despite the advantages of electric jeeps, there are still commuters who prefer to stick to what they are used to.

Maria Rezayde Perez, 45, said she will follow what the government mandates, but she still prefers riding the traditional jeeps to take her son to school every day.

“It’s what I grew up with. Jeepneys are the mark of the Filipino. Even foreigners come here to ride the jeep. It is a national symbol,” she said.

South Metro Transport Cooperative’s Saw said that as an operator, he does not feel any nostalgia towards the old jeepneys. Jeepneys that date as far back as the 70s are bound to break down eventually, and he used to worry that his old vehicles would get caught by random inspections and he would be fined as much as ₱5,000 (US$ 97) for every screw loose or fizzled light bulb.

“It will be nice to have some of the old jeepneys around, but maybe just in tourist areas. On everyday routes, their time has passed,” he said.

“The weather is changing. Sometimes it’s hot then all of a sudden it starts raining. We have to take care of the environment for the future of our children. We’ll soon feel the advantages of solar and electric energy and the next generation will thank us for it,” he said.

Want more Philippines ESG and sustainability news and views? Subscribe to our Eco-Business Philippines newsletter here.