Protection of the Amazon rainforest, the most biodiverse place in the world, suffered a setback earlier this month when the eight countries that share the jungled region’s vast territory failed to sign a no-deforestation pledge at a conference in Brazil.

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

It disappointed environmentalists and Indigenous groups who had hoped the deal could demonstrate a new model for regional cooperation to protect biodiversity hotspots.

What happened at the “Amazon summit” halfway across the world mirrors conservation challenges facing Southeast Asia, another of such forest hotspots, experts say.

But short of a regional pledge – a feat not attempted in Southeast Asia – they believe that multilateral cooperation can still lead to better conservation, along with focusing on action that benefits all stakeholders.

“The failure of the Amazonian countries to agree on a no-deforestation pledge demonstrates the socio-political challenges of reconciling domestic economic agendas with regional environmental protection priorities,” said Professor Koh Lian Pin, director of the Centre for Nature-based Climate Solutions at the National University of Singapore.

“The same could be said of the Southeast Asian region, where each country also has to grapple with the trade-offs of development versus conservation,” Koh said.

Southeast Asia houses 15 per cent of the world’s jungles, and Indonesia has the third-largest rainforest globally, after the Amazon and Congo regions.

At least until recently, both the Amazon and Southeast Asia also had high deforestation rates – Southeast Asia lost a sixth of its forests between 1990 and 2020; the Amazon marginally less, losing one seventh of its forest cover.

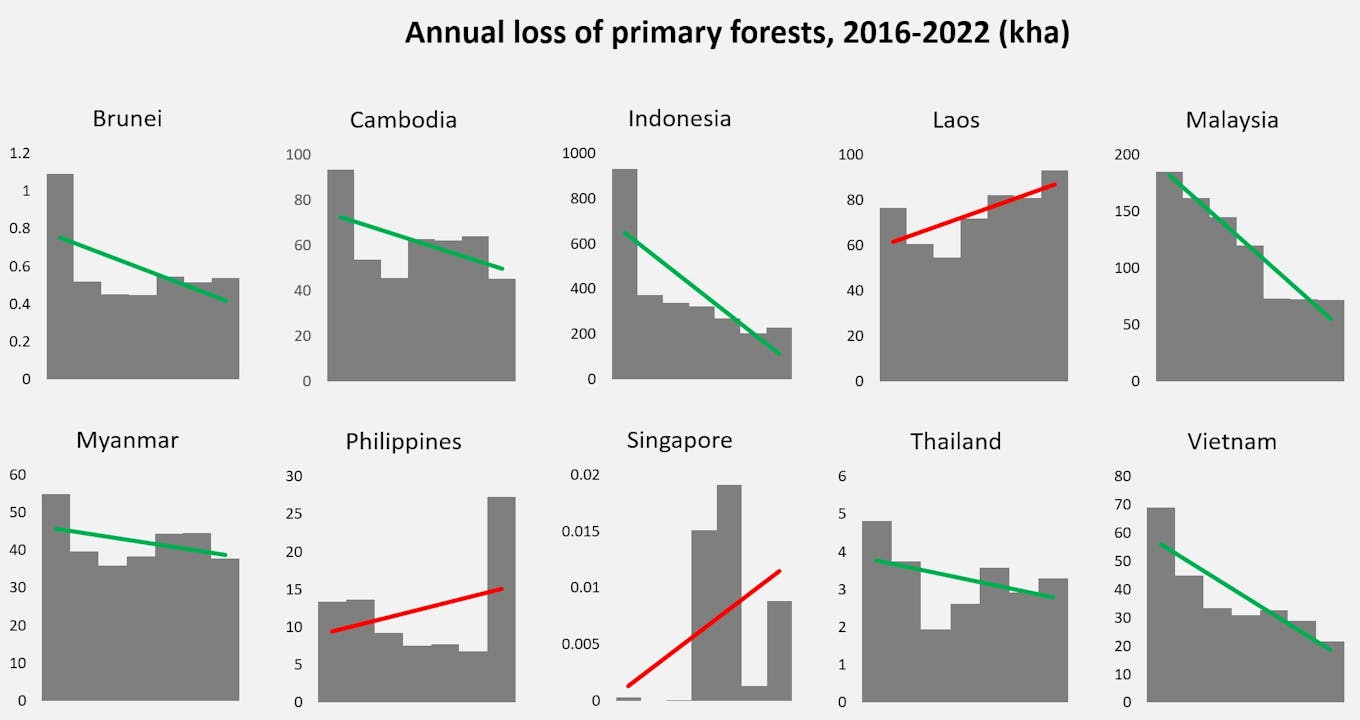

Both regions are rapidly developing, with agricultural and urban developments encroaching into pristine natural areas. But while deforestation trended upwards in the Amazon since 2015, forest loss rates in many parts of Southeast Asia, particularly in Indonesia and Malaysia, have been declining against a 2016 high. Still, primary forest loss is climbing in countries like Laos, the Philippines and Singapore, the latest data shows.

Primary forest loss in many Southeast Asia countries have been on a downward trend from 2016 to 2022, though rates have been creeping back up in countries like Laos, Philippines and Singapore. Data: Global Forest Watch.

To date, the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (Asean) bloc has not floated regional no-deforestation pledges. Individual countries have made commitments, though not all appear watertight.

At 2021’s COP26 climate summit, eight Asean countries including Cambodia and Indonesia signed a global pledge to stop forest loss by 2030. However, Cambodia’s own national climate plan only commits to halving deforestation by then, and Indonesia had later backtracked on the target.

At 2022’s COP27, a similar global pledge against deforestation, seen as a follow-up, only had Vietnam and Singapore as signatories. Indonesia expressed interest but made no firm agreement.

Indonesia signed a US$56 million deal with Norway last November to prevent deforestation, after the two nations terminated a similar agreement in 2021 over payment issues.

No-deforestation commitments would have a stronger impact on a regional scale, since would mean that countries implement similarly strong policies, said Hidayah Hamzah, senior manager for forest and peat monitoring at non-profit World Resources Institute (WRI) Indonesia.

Hamzah noted there are existing regional initiatives protecting cross-border ecosystems, such as the Mekong river basin, running through China and several Southeast Asian nations. Non-profit WWF also has a forest conservation programme on Borneo island with the governments of Brunei, Indonesia and Malaysia.

“These commitments are a great first step, but more important are policy implementation in forest protection and law enforcement,” Hamzah said.

“It may not be productive to overly fixate on a no-deforestation pledge because a pledge on its own is just that, with no guaranteed outcome,” Koh said. A “common vision of a desired and sustainable future” that is science-based and involves the public and businesses is far more impactful, he added.

Such an approach involves a “longer and potentially painful” process of balancing conservation with ensuring equitable transition for communities that need more time, Koh said.

“Even without regional pledges, Southeast Asia has shown remarkable progress with regard to reducing deforestation,” said Dr Dindo Campilan, regional director for Asia at the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) – also citing examples of Indonesia and Malaysia, as well as Vietnam.

Regional networks in the region help with capacity building and rallying support, he noted, citing initiatives within the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (Asean), and the Asia Protected Areas Partnership which IUCN co-chairs.

The Asean bloc of 10 Southeast Asia countries has a 10-year action plan through to 2025, to eradicate hunger while “achieving sustainable forest management” – though quantitative targets are not set for conservation.

Campilan said steps such as stronger action against illegal logging, providing fiscal incentives, setting up protected areas and helping Indigenous communities secure land tenure have been shown to work in the region.

The scrutiny of palm oil, for which Indonesia and Malaysia are top global producers, has also resulted in stronger regulations and voluntary corporate no-deforestation commitments, Campilan noted.

But the measures have not placated everyone – the sustainable palm oil certifications of both countries have yet to be recognised by the European Union, which is set to ban the import of commodities linked to deforestation next year.

Greater data transparency from governments and businesses is also needed for monitoring and accountability, Hamzah said, noting that some information such as on forest concessions is still not publicly available.

Indonesia stands out among tropical countries for reducing deforestation, the main driver of which is now mining. Image: IndoMet in the Heart of Borneo, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Flickr.

Meanwhile, the failure of Amazon countries to commit to a no-deforestation pledge appears to have some uniquely local traits. Colombia had, unpopularly, used the same platform to lobby for an end to new oil development in the Amazon, Reuters news agency reported.

Brazil has also been a wildcard in recent years. After Amazon deforestation soared for years under previous president Jair Bolsonaro, conservation has now become a national priority under the new administration led by Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva – who had pushed for the regional conservation pledge. A personality like Lula arguably does not exist among Southeast Asian heads of states.

While deforestation in the Amazon continues to be driven by agriculture, forest loss in Indonesia is now primarily caused by mining.

“While a similar no-deforestation pledge could benefit Southeast Asia, it must be tailored to address the region’s distinct challenges,” said Tomi Haryadi, deputy programme director for agriculture, forest, and land use at WRI Indonesia.

Money matters

The Amazon nations, in a “Belem Declaration“, nonetheless agreed to better protect Indigenous peoples and collaborate on sustainable development.

There was a separate agreement involving other forest-rich nations, such as the Democratic Republic of Congo and Indonesia, to call for more conservation funding from wealthy countries.

The world had pledged last December to raise at least US$200 billion a year for biodiversity conservation by 2030, and to protect 30 per cent of the Earth’s lands and seas by then. But there is scepticism over fund disbursement, as a landmark US$100 billion climate finance pledge for 2020 had fallen short by 20 per cent.

Analyst Sustainable Fitch said the financial demands issued during the Amazon summit could set the stage for a “more confrontational COP28 [global climate summit] this year, with developing nations unifying more strongly in their calls for follow-through on existing pledges and additional climate finance from developed nations”.