On a barge off northeastern Singapore, underwater cameras monitor barramundi and red snapper swimming in large tanks that can hold 1.8 million litres of water each.

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

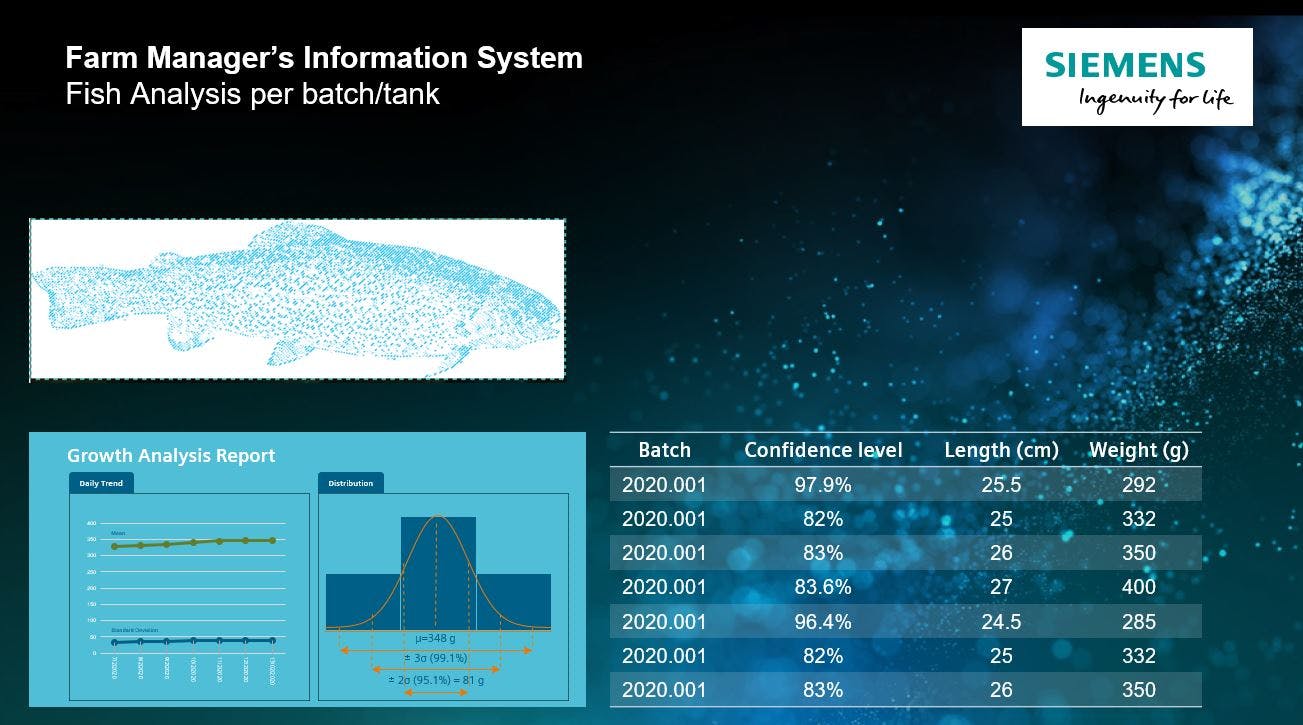

The cameras are part of a digital system that monitors how well the fish are feeding, their growth, health and mortality rate. It also uses artificial intelligence to make increasingly precise analysis and predictions of the fish.

The farm uses a recirculating aquaculture system that allows the water conditions to be controlled and unaffected by the surrounding seas. Water in the closed containment system is recirculated and requires only a 5 to 10 per cent top-up each day to make up for losses through evaporation. The water used for top-up is taken from the surrounding sea, and is filtered and sterilised to get rid of pathogens.

Solar panels and batteries on the farm provide the bulk of its energy needs, while the remainder is supplied by diesel.

The digital and monitoring platform developed by Siemens. Image: Siemens

The farm, measuring 100 by 27 metres, is operated by a company called Singapore Aquaculture Technologies (SAT). It began operating a few weeks ago and was officially launched on Monday (17 February) at a ceremony attended by Singapore’s Minister for the Environment and Water Resources Masagos Zulkifli, Germany’s Ambassador to Singapore Dr Ulrich Sante and other guests.

When operating at full capacity next year, it expects to yield 250 tonnes of fish a year, said SAT co-founder Dirk Eichelberger.

Touted as a “smart floating fish farm”, Dr Eichelberger said it is setting new standards in Singapore’s aquaculture industry and is a solution that can be scaled and rolled out to the rest of the region.

“We are living in challenging times and water quality is varying, no matter where you are,” said Dr Michael Voigtmann, SAT’s chief technical officer.

“What recirculation technology lets you do, is be completely independent of water (conditions outside the farm, which could be affected by) a chemical or oil spill, harmful algal bloom or massive rainfall, which washes a lot of runoff into the ocean and which causes temperatures to drop. All these things make fish uncomfortable,” he said.

Recirculating systems enable fish to be reared in consistent conditions, which reduce the chances of them contracting illnesses, and the need to feed them antibiotics, said Voigtmann, who added that the farm cost just over S$3 million to set up.

Recirculating aquaculture system used at SAT’s fish farm. Image: Eco-Business

Aquaculture is a cause of water pollution worldwide as uneaten feed and fish excretion enter the seas. This affects nutrient content in the water, which can lead to events such as deadly algal blooms that harm other marine life.

Recirculating aquaculture systems are a first step towards reducing the chemical load on oceans, giving the water bodies a chance to recover, said Voigtmann. SAT is also looking to use some of the waste produced by fish to grow microalgae, which it will harvest and turn into a protein product.

Other fish farmers in Singapore that are using recirculating aquaculture systems include Apollo Aquaculture Group, which is in the midst of building an eight-tier land-based farm in Singapore’s Lim Chu Kang agricultural zone. When completed by 2023, it expects to produce an estimated 2,400 tonnes of fish per year. The company is also looking to set up operations overseas and has started a project in Brunei.

Such production volumes will make a dent on the local landscape. In 2018, Singapore farms produced 5,915 tonnes of fish and 613 tonnes of other seafood, government statistics show.

At the launch of SAT’s new farm, Masagos said Singapore—which imports more than 90 per cent of its food but is looking to meet 30 per cent of its nutritional needs locally by 2030—will continue to use less than 1 per cent of its land for agriculture.

In the face of climate change, food production must be high-yielding, as well as climate resilient and resource-efficient, he said.

SAT’s digital system, developed by German engineering giant Siemens, allows staff to monitor each of the barge’s 10 tanks, and will sound the alarm when there are abnormal fluctuations in water conditions.

Going forward, it plans to build a hatchery on the second storey of the barge and adopt blockchain technology to ensure traceability of its fish from egg to harvest, said Eichelberger. Consumers would then be able to scan a QR code to get information about the fish they are eating.