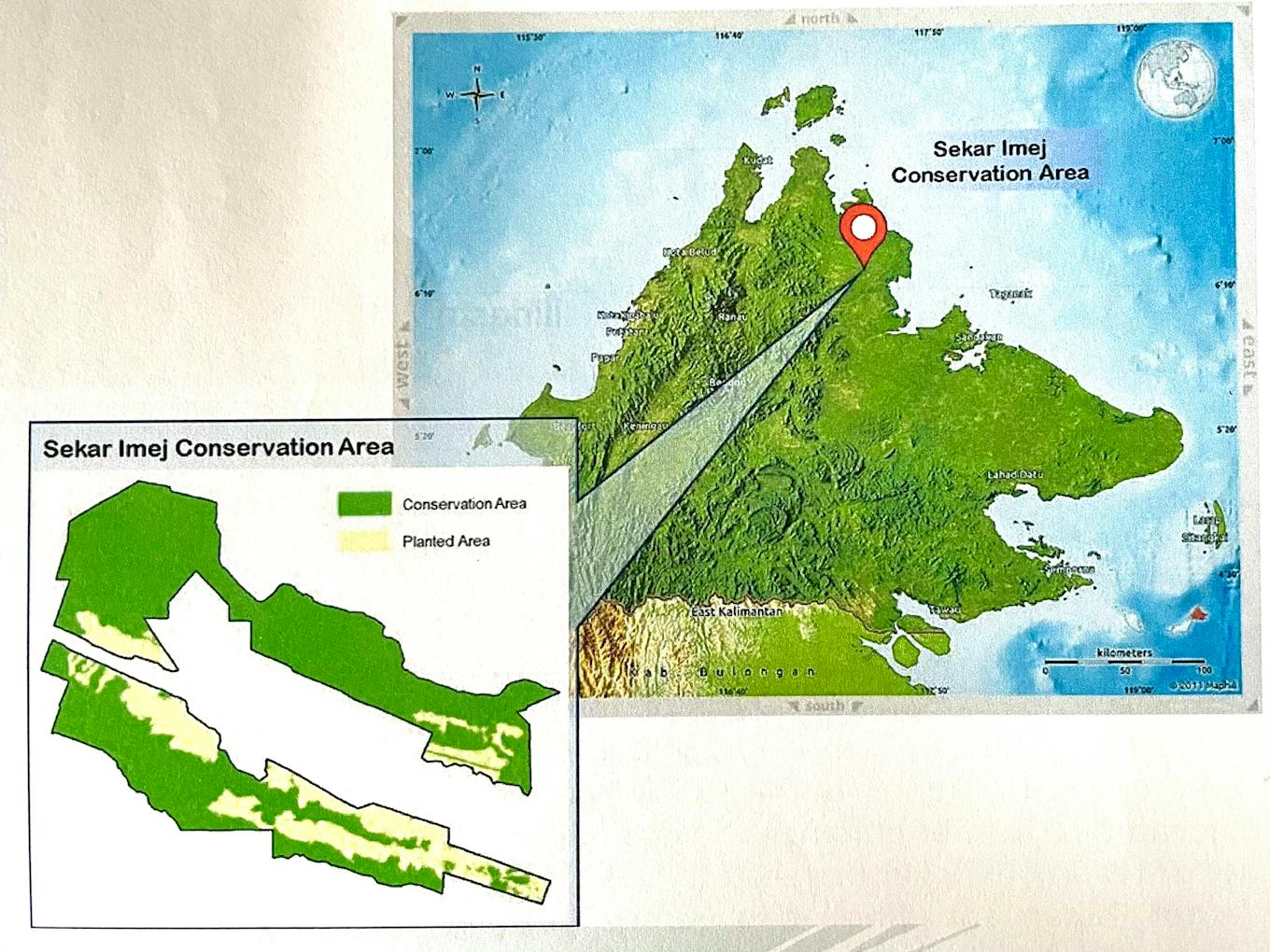

When oil palm giant Wilmar International decided to turn 2,469 hectares of its unplanted land in Sabah, Malaysia into a conservation area and invite researchers to study the degraded forest, it did not expect to receive much interest from the scientific community.

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

Researchers from Universiti Malaysia Sabah collect live termite samples from a log in the Sekar Imej Conservation Area located in the Beluran district of Sabah, Malaysia. Image: Lim Sheng Haw

Nearly 60 researchers from Universiti Sains Malaysia, Universiti Malaysia Sabah and Wilmar’s long-time conservation partner the South East Asia Rainforest Research Partnership (SEARRP) signed up for a two-week scientific expedition to the Sekar Imej Conservation Area (SICA) from mid- to end-September. Eco-Business, along with other members of the media were invited by Wilmar and SEARRP to visit the site at the tail end of the expedition, which involved 48 researchers.

Initial findings from the trip, which the scientists described as a rare opportunity to access a protected area in the Beluran district, indicate that the plots of largely lowland mixed dipterocarp forests is teeming with biodiverse flora and fauna, including rare, threatened and endangered species, despite having been logged over in the 1980s.

The expedition, focused on collecting baseline data about key species in SICA, has also triggered the interest for scientists to do further research on habitat restoration and regeneration in other previously logged forests like the one demarcated by Wilmar, said Dr Glen Reynolds, SEARRP director and the expedition’s project lead. This includes looking into how areas once cleared for planting oil palm trees can be restored to become biodiverse forests.

“What’s unique about this opportunity is that Wilmar is prepared to set these areas up on an experimental basis when the research questions want to test are mostly hypothesis-driven, which is very, very rare,” said Reynolds.

Scientists are hoping to understand what “reverse engineering” a degraded forest would involve, he said. “We know quite a lot about what happens when a forest is fragmented, or how biodiversity is impacted by logging. What we undestand less is how to reverse that process.”.

“That is why we jumped at this opportunity,” added Dr Nik Fadzly N Rosely, associate professor of ecology at University Sains Malaysia.

A map view of the Sekar Imej Conservation Area in the Beluran District of Sabah. Image: Wilmar International

The scientists hope to continue returning to SICA on regular basis over the next few years to continue observing these species, something Wilmar is keen on supporting. To ensure that the research being conducted is independent of corporate interests, Wilmar will only cover the cost of accommodation and food for visiting researchers.

“By repeating the survey two years and then five years later, we are able to observe trends such as the change in species, the number of species present, the diversity of animals, their compositions and so on,” explained Henry Bernard, professor at The Institute for Tropical Biology and Conservation, Universiti Malaysia Sabah. “We will not know if this forest area is meaningful unless we begin the research right now and repeat it over time.”

Degazettement danger

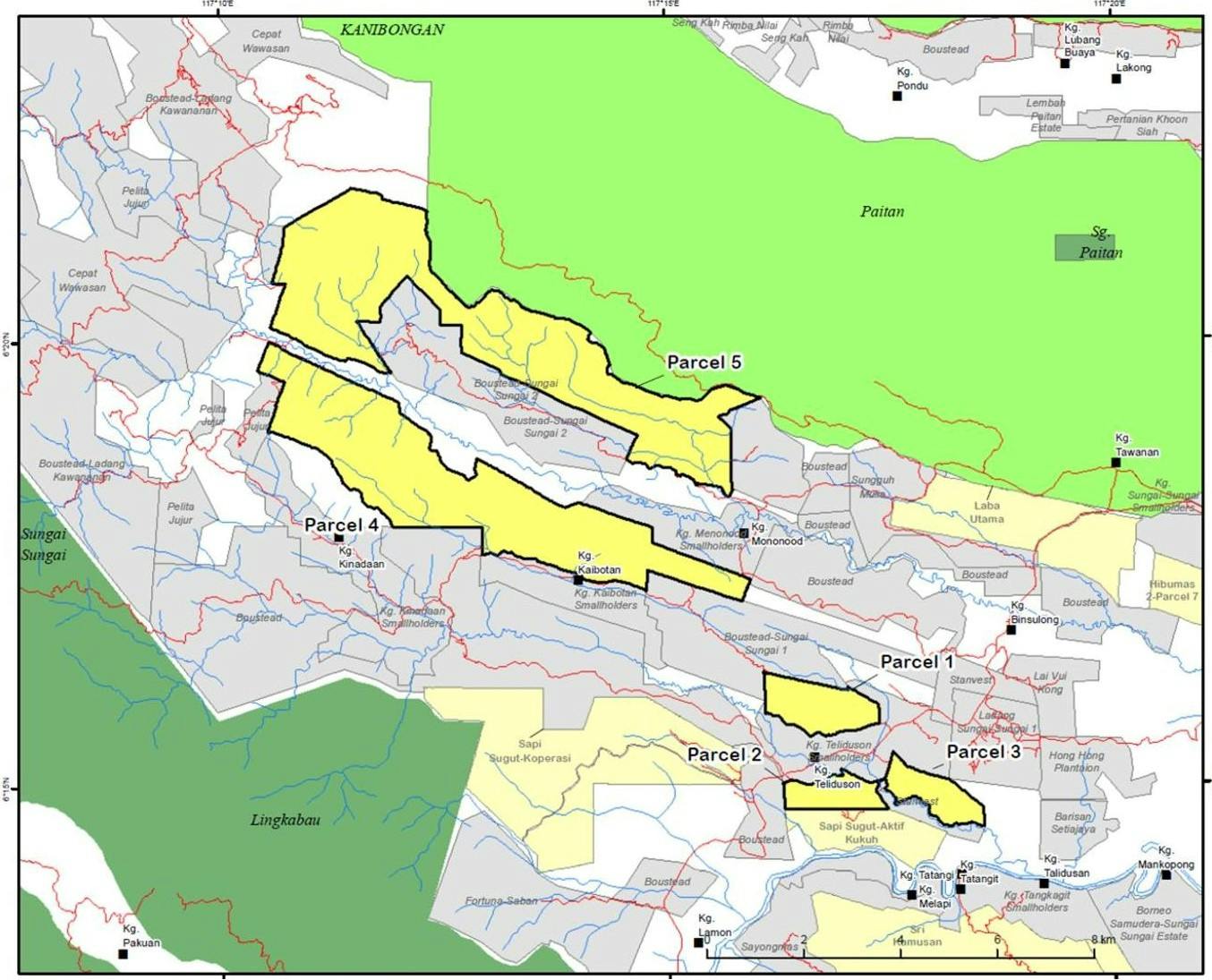

Time is of the essence to the scientists as part of the Paitan forest reserve that borders SICA to the north has been degazetted, increasing the risk of poaching and potentially disrupting its function as what Reynolds calls a “staging post” for animals between different forest reserves. This could be a patch of forest that animals can find cover in as they travel from one habitat to another.

It is unclear whether SICA serves this function, but scientists hope that further research will help answer this question.

The Paitan reserve is categorised as a Class 2 forest reserve by the Sabah state government, which means it is a commercial reserve allocated for timber harvesting according to sustainable forest management principles.

“If you lose forests, that is going to have a serious impact on biodiversity and potentially a very serious effect on SICA. That will be something that Wilmar will need to consider to under its oblications to maintain the stability of the conservation area,” Reynolds said.

“

The biggest problem in biodiversity conservation is: how do you pay for it? The minute the government sets aside land as protected area, that land is no longer generating any income for them to run the country.

Lahiru Wijedasa, Asia forest coordinator, BirdLife International

Wilmar was informed of the degazettement via a letter in late 2019, said Perpetua George, the company’s general manager of group sustainability. It has not engaged with local authorities on how SICA will be affected by the commercial activities planned for the degazetted plots.

The degazettement adds to the difficulty of protecting SICA due to the two conservation plots being separated by a stretch of palm oil plantations belonging to another Malaysian oil palm company, Boustead Plantations, and several smallholders, as well as a river managed by the Department of Drainage and Irrigation, George said.

The degazettement has raised the question among the scientific community as to whether forests are better conserved in the hands of private companies such as plantations firms.

“The biggest problem in biodiversity conservation is, how do you pay for it? The minute the government sets aside land as protected area, [that land] is no longer generating any income for them to run the country,” said Lahiru Wijedasa, Asia forest coordinator at BirdLife International, who has researched tropical forests including in Malaysia and Indonesia.

“Even if a you fund a [state-owned] protected area, you can’t really get the kind of conservation done that you can get with privately-owned land, because on privately-owned land you can set higher standards. And you may have the money and jurisdiction to do it,” he said.

Locals now refer to the forests that make up SICA as an “icebox”, previously treating the area as their hunting ground for fresh meat such as wild boars and other mammals, according to Wilmar’s conservation programme lead for Malaysia, Chin Sing Yun. Wilmar has worked with the Sabah Wildlife Department to train locals from three nearby villages as honorary wildlife wardens, whom they have hired on a full-time basis. The department also runs community engagement programmes to explain their conservation work.

A map showing the Paitan Forest Reserve bordering Wilmar’s Sekar Imej Conservation Area (SICA). A patch of the forest reserve bordering SICA has been degazetted for commercial use. Image: Wilmar International

To better protect SICA, Wilmar in collaboration with SEARRP has applied for the area to be recognised as a protected area using Other Effective Area-Based Conservation Measures (OECM), which could increase recognition and support of conservation efforts within the site.

Wilmar will have to consider the impact of biodiveristy loss due to the degazettement of a portion of the neighbouring Paitan, under its oblications to maintain the stability of the conservation area, said Dr Glen Reynolds (centre), director of the South East Asia Rainforest Research Partnership (SEARRP). Image: Lim Sheng Haw

Money matters

As one of the largest oil palm planters in Southeast Asia, Wilmar is no stranger to having come under criticism for its environmental and social practices by environmental groups like Greenpeace. In 2013, the Singapore-headquartered company was one of the first oil palm plantation firms to commit to a “no deforestation, no peat, and no exploitation” policy.

Critics point to how Wilmar’s total high value conservation area in Sabah is only 6,775 hectares, 13.6 per cent of its total land area of. The ratio is similar across its international operations, with a total of 13.9 per cent of land conserved compared to its total planted area in Malaysia, Indonesia, Uganda and West Africa.

“Considering how big and profitable Wilmar is, 2,000 hectares is nothing for them,” said Wijedasa. “If a company like [pulp and paper manufacturer] APRIL can match one hectare of forest conserved to every one hectare of plantation, the question for Wilmar is, what can they do next?”

Claw marks made by a Bornean sun bear can be seen on a tree in the Sekar Imej Conservation Area. Image: Samantha Ho/Eco-Business

“2,000 hectares is a good start, but it is far from where they should be,” he told Eco-Business.

As a profitable conglomerate – Wilmar posted a core profit of US$1.8 billion in 2021 – the group is well-positioned to absorb the costs of managing SICA.

George acknowledges that were it a standalone conservation area, SICA would not be able to sustain itself financially as it is not generating any revenue or income for Wilmar, which bears the conservation-related costs such as manpower, vehicles and other infrastructure to ensure the site is protected from encroachment.

Similar private conservation efforts by private landowners in Indonesia have yielded positive results, such as the UNESCO-recognised Giam Siak Kecil biosphere reserve in Northern Sumatra, which was originally concessioned to Asia Pulp and Paper, and the Tambling Wildlife Nature Conservation founded by Indonesian businessman Tommy Winata, which consists of more than 45,000 hectares of forest and an additional 14,000-plus hectares of marine conservation area.

“I think it is important that companies are doing this, because we are at a critical point where biodiversity is vanishing. And we might not have the building blocks to fight climate change [without private conservation areas],” said Wijedasa.

“We need as many partners as possible and we need partners who have available funds and the ability to call the shots, to get things done. The more partners the better, especially the big players,” he said.

Media access to the sponsored SICA expedition was facilitated by Wilmar.

Clarification: An earlier version of this article mentioned locals hunting in the conservation area. Wilmar has clarified that hunting is prohibited in SICA.